Diplomatic

(without tears)![]()

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Reading Manuscripts | ||

| A number of skills must be brought to bear to decode medieval manuscripts. They are the same skills which you are using now to decode this page, but because your subconscious is steeped in the code of modern communication, you donít have to think about how you are doing it. You may even have the radio on to occupy an unused corner of your brain while you are processing the information. Nevertheless, you are simultaneously comprehending the structure of the language, detecting the pattern of the script (or font, given that this is computer generated), noting the significance of the punctation, decoding any abbreviations (eg. like this one) and looking at the structure of the document as a whole. |  |

|

| Two headless figures carved on the side of a tomb in Lincoln Cathedral sit with a book between them, obviously competent at medieval paleography. | ||

| In other words, you are already fully cognisant of the practices of paleography and diplomatic. You just have to put them into a medieval context. The art of medieval paleography involves an understanding of the history of scripts and an ability to decode unfamiliar letter forms as well as learning how scribes of the past used punctuation and abbreviations. | ||

| The details, and it is a subject of multiple details, are in the What is Paleography? section, while a series of interactive exercises to help you learn these skills are in the Paleography Exercises section. | ||

| The term diplomatic refers to the structure of a document. Legal or business documents tend to follow certain formulaic structures which change over time. Knowledge of these formulae makes reading the document easier, as you identify the standard sections and save the most energetic brain work for the unique and individual substance of the text. Knowledge of the way document structures change over time and place also allows diplomatic to be used for dating and sourcing documents. | ||

| Finally, you need the necessary language skills. A large proportion of medieval documents, particularly ecclesiastical, legal or state documents, are in Latin, particularly in the earlier part of the medieval era. | ||

|

||

| The beginning of a Latin charter of William I, with abbreviations. (From Wright 1879) | ||

| Vernacular languages make their appearance at various times, and become much more common in the later medieval era. However, the familiar languages such as English and French have undergone great change during the course of the medieval era. Old English, from the Anglo-Saxon era, is relatively incomprehensible to us today. Even the Middle English of Chaucerís era is very difficult. | ||

|

||

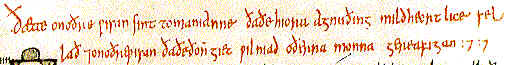

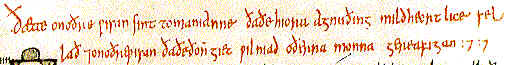

| Heading from St Gregory's Pastoral Care in Old English, from the Bodleian Library (Hatton MS 20, f.61). (From New Palaeographical Society 1903) | ||

| Would it help to know that a modernised transcription of the above passage reads Thaette on othre thisan sint to manianne tha the hiora agnu thing mildheortlice sel lath ond on othre thisan tha the thonne giet wilniad otherra monna gereafigan? I thought not. | ||

| The standardisation of spelling is a relatively modern phenomenon, and as an Australian who had a couple of crucial years of early education in America, I can confirm that the process was never really completed. The changes run much deeper than just spelling and the more delicate rules of grammar. In the long chronology of medieval, this was the era in which modern European languages were formed. | ||

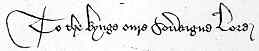

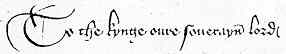

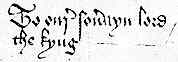

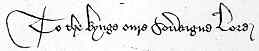

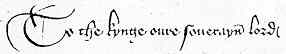

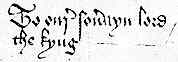

| Assorted spellings referring to the king, our sovereign lord in 15th century petitions in the National Archives, London (E.28/60/38, E.28/79/30, E.28/59/57), by permission of the National Archives. |

|

|

|

||

|

||

| There are many published aids to learning all these tricks, and every practitioner of the art of medieval document reading becomes a specialist in their favourite class of manuscript. The basic skills are not so hard to acquire. | ||

Diplomatic

(without tears) |

||

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||