|

|

Vernacular

Languages |

|

The

use of vernacular

languages for the written word had something of a fluctuating history,

with a general tendency to increase towards the later part of the middle

ages. Languages are the most powerful symbol of ethnic identity. The encouragement

or repression of vernacular literacy has tended to coincide with the expression

or suppression of national or ethnic boundaries. |

|

The

use of vernacular languages in written works of any type cannot be divorced

from events and politics. The adoption of forms of Roman civilisation

by the Ostrogoth conquerors of Rome resulted in the production of Bibles

and other Christian texts using the Gothic

language. These are now mainly known only from palimpsests. |

|

Literacy

was re-established in Anglo-Saxon society through the church and was therefore

grounded in Latin. However, a cultural and ethnic revival in the 9th century

under the influence of Alfred the Great resulted in the production of

works in Old English.

These included Biblical texts, histories and religious commentaries and

were, in fact, Latin works translated into English rather than a recording

of the cultural heritage of English oral tradition. The famous manuscript

of Beowulf, an epic saga from oral tradition, is in fact known from only one copy produced probably

hundreds of years after the composition of the tale. |

|

|

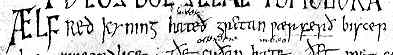

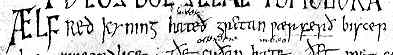

Beginning

of the preface to St Gregory's Pastoral Care in Old English

(Bodleian Library, Hatton MS 20, f.1) with reference to Aelfred

kyning. |

|

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a historical

text in Old English chronicling events in England up to and shortly after

the Norman Conquest. There are several copies in slightly variant versions,

varying mainly in the additions at the end of the time period. This can

be seen as an attempt to transform an oral tradition into a literary format;

the new beginnings of literary history.

|

|

The

use of Old English in literary or religious works largely ceased after

the Norman Conquest. The later Anglo-Saxon kings had issued writs

in the vernacular. After the Conquest, royal charters

were occasionally issued in bilingual form, duplicated in Latin and Old

English. Each language was written in its own particular script.

Less solemn legal transactions may sometimes be found in the vernacular.

Vernacular terms were also included in Latin charters to describes rights

or privileges known in Anglo-Saxon law. |

|

|

|

|

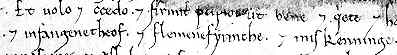

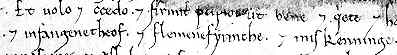

In

a Latin charter of Henry I to Westminster Abbey (Westminster Abbey Muniments

No.XXXI). |

|

The rights and privileges which were confirmed in the example above included

infangenetheof and flemenefyrmthe among other Old English mysteries. |

|

England

was, of course, linguistically divided at this time. English was the language

of the lower classes and of the conquered, while Anglo-Norman

or Norman French was the language of the conquerors and those who wished

to be counted as the aristocracy. Anglo-Norman is rarely encountered in

formal documents, although it can be found in Parliament Rolls,

Privy Seal documents

and private correspondence predating the 15th century, as well as in some

historical works. |

|

Scandinavian

vernacular saga texts were also only recorded in manuscript form centuries

after their composition. In areas peripheral to the establishment of literate

Latin based engines for the main motivating forces of society, such as

Iceland, manuscripts with many formal qualities in common with those of

mainland Europe recorded sagas from oral tradition in the late middle

ages and into the 17th century. |

|

|

Irish

was also written as a vernacular language in the earlier medieval period.

The existence of secular schools of versecraft, historical and genealogical

lore and secular law is known from the 7th century, but their original

manuscripts do not survive. However, 8th and 9th century Old

Irish glosses and commentaries on Latin texts from the monasteries

are known. |

|

Irish

monastic scribes of the 11th and 12th centuries recorded secular material

such as saga texts in the vernacular. Such work disappeared from the monastic

corpus with reform of Irish monasticism and the introduction of orders

such as the Cistercians and Augustinians. |

|

|

Ruins

of the Irish Cistercian Abbey of Bective. |

|

|

Reading Manuscripts

Reading Manuscripts |

Why Read It?

Why Read It? |

|

|

|

|

|