|

| Medieval French |

|

The national language of France, which we call French, is really a product of the medieval epoch. As with so many other vernacular languages, it is hard to trace all the stages of language development because so many of them were never part of the written tradition. The earliest known languages used in what we define as modern France were Celtic dialects, related to the Gaelic of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Cornwall. The Scots people who still speak their ancient native tongue refer to it as Gallic rather than Gaelic. Are we seeing a connection here? The only survivor of this language family in France is the ancient language of Brittany, Breton, despite ferocious attempts to quash it in post-medieval French nationalist fervour, under the misguided assumption that the only path to national unity is to all speak one language. |

|

|

| At left, Roman temple at Nimes; at right, the Porte de Mars in Rheims, a Roman ceremonial gateway. |

| The conquest of France by the Roman armies left relics of ancient Roman culture all over the landscape. The most spectacular architectural remains are now in the south, but occasional relics have survived in other areas. The Roman Empire not only brought the official imperial language of Latin into France, it brought in people from many parts of the empire. Latin, not in the lavish literary form that survived in the Classical writings but in a plain, simplified and functional form that allowed people to buy and sell and carry out other everyday functions, was the one language that many people had in common. It is impossible to know how many dialects and varieties developed around the countryside, but the term lingua romana has been used to describe the language or languages that developed. |

|

The official adoption of Christianity in France introduced literacy through the medium of the church, and as everywhere, that was Latin literacy. The earliest histories, such as that of Gregory of Tours, a senior churchman, are Latin texts. |

| A modern statue of the baptism of Clovis at Rheims, on the site where the event supposedly took place. |

| During the so-called barbarian invasions that accompanied the collapse of the Roman Empire, there were significant movements of people around Europe, and no doubt much language interaction. The Franks, who became the elite in France, spoke a Germanic language. The literate mechanisms of government were tied to the literacy of the church, and therefore conducted in Latin. Merovingian diplomas were in Latin. By the time of Charlemagne in the early 9th century, his biographer Einhard reported (in Latin) that among the great emperor's literary talents, he had caused to be recorded many legends from the Frankish tradition in their native language. If so, they do not survive. Frankish evidently added some words to the lingua romana, but essentially these languages were the domains of different sections of society. |

|

A depiction of Charlemagne in Frankish dress. |

| Charlemagne's empire was a fragile thing, and so were his family relations. After his death, the division of his kingdom was plagued with intrigue and violence such as would send a modern family counsellor to drink. In 842 two of the grandsons of Charlemagne, Louis the German and Charles the Bald, took an oath in front of their armies to gang up against the rest of the family. The army of Louis was made up of Germanic speaking men, while that of Charles came from southern and western France and included included people of Roman and Gallic heritage as well as those of Frankish origin. To keep faith with and be understood by the men of each other's army, Louis took his oath in the lingua romana while Charles took his in the lingua teudisca, the progenitor of modern Germanic languages. Fortunately, somebody wrote it down. (I wonder how those present actually heard it!) |

|

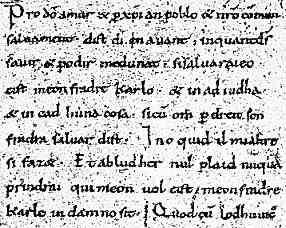

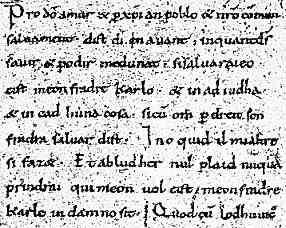

The Strassburg oath in the lingua romana, from a 10th century manuscript of the chronicles of Nithard (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale MS latin 9768). |

| Pro deo amur et pro christian poblo et nostro commun saluament dist di in auant, in quant deus sauir et podir me dunat, si saluareio cist meon fradre Karlo et in adiudha et in cadhuna cosa sicum om per dreit son fradra saluar dist. In o quid il mi altresi fazit. Et ab ludher nul plaid numquam prindrai qui meon uol cist meon fradre Karle in damno sit. |

| The two versions of the oath were written down by a contemporary chronicler, Nithard, and inserted into his Latin account of the occasion. They are considered to be the earliest surviving examples of both the French and German languages. The surviving copy, however, is not by his own hand but is from a 10th century manuscript copy of the work, as illustrated above. The evolution of piggy Latin into French is documented by this tiny, and possibly inaccurate, scrap. |

|

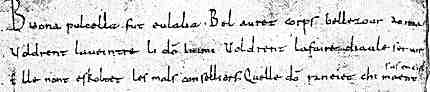

| A small grab from the Cantilene de Sainte Eulalie, from a 10th century manuscript (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale). |

The Cantilene de Sainte Eulalie, shown above also in a 10th century copy, represents another piece of early French or lingua romana from the later part of the 9th century. It is considered to be the earliest French poem; that is to say, the earliest which has survived.

Other examples of the early French language are scanty. A few words of liturgical chant, some glossary words, a few short religious poems. It is not until the production of lavish volumes of vernacular literature begins in the 12th century that the scope and variety of the newly developed French language becomes apparent in the written word. |

|

continued

|

Reading

Manuscripts Reading

Manuscripts |

Why Read It? Why Read It? |

|

|

|

|

|