If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Histories, Chronicles and Annals (3) | |||

| While the concept of building on written works from the past, and then adding detail which might have owed something to imagination, was an established tradition, one author took this concept further than most, with some interesting consequences. In 1138 Geoffrey of Monmouth completed his Historia Regum Britanniae (The History of the Kings of Britain), a work which purported to be the history of British origins and the struggle against the invading Anglo-Saxons. It was a popular work, and survives today in over 200 extant manuscript copies. The part of it which is best known today is that which tells the story of the mighty King Arthur, his conquests and his final departure, not death, to await his country's needs. It is a genuine myth, embodying ethnic construction, moral struggle, god-like heroes and future promise. |

|

||

| The bleak cliffs of Tintagel in Cornwall with the (much later) medieval castle on top are one of the many sites associated with the legend of King Arthur. | |||

| If you type "King Arthur" into a web search engine, your computer will probably overload and melt, such is the popularity of the myth, its multiple retellings and earnest efforts to uncover the truth behind it. A good place to investigate the development of the story and read the Arthurian sections of the work is The Camelot Project. You can read this work in ye olde paper book in Thorpe, L. (ed. and trans.) 1966 Geoffrey of Monmouth: The History of the Kings of Britain Harmondsworth: Penguin or on the web at Geoffrey of Monmouth. | |||

| Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed a previously unknown source for his new history; a very ancient book written in the British language presented to him by a friend, Walter the Archdeacon. There are many episodes described in Geoffrey's history, most quite briefly in chronicle format, but three of them are expanded to occupy disproportionate quantities of the text. One is the founding of Britain by one Brutus, grandson of Aeneas of Troy. This person did not exist. Another was the story of Belinus, who sacked Rome. This event did not happen. The third was the story of Arthur and the predictions of Merlin. | |||

|

|||

| Glastonbury Abbey did very well for itself as a place of pilgrimage, having had the good fortune to discover the bodies of Arthur and his Queen Guinevere in their cemetery, despite the fact that Arthur was supposed to be resting up on Avalon before making his big comeback. | |||

| No very ancient British book, or other literary trace of it, survives. Theories regarding its existence have been debated for centuries. The most unpopular theory is that it never existed at all. Alternative theories are that he had at his disposal various Welsh manuscripts which now only exist as later copies and fragments, which is quite possible. It has been surmised that the term "ancient book" was a symbolic reference to oral tradition, in which case Geoffrey would have been doing something rather radical in the medieval literate tradition; converting oral knowledge into the kind of authority that was normally reserved for serially recopied written works. It has even been suggested that he pinched the work from an anonymous contemporary and that the "ancient book" may have been quite modern. Surely not! | |||

|

The only surviving references to Arthur which predate Geoffrey of Monmouth are in the works of the 6th century chronicler Gildas, who refers to a battle at a place called Mount Baden, wherever that might have been, and an elaboration on the tale by the 8th century chronicler Nennius, who claims the name of the victorious British general there was Arthur. There is no sword in a stone, no prophesying wizard, no "watery tart brandishing a sword" to quote the Monty Python version. Whatever sources Geoffrey used, either historic or legendary, he created the most significant myth ever to define British origins and character. | ||

| The Round Table in the great Hall of Winchester Castle. | |||

| The Round Table in the hall of Winchester Castle has been believed to be a Tudor fake, created as a symbol of the desire of the Tudor monarchy to identify themselves as the proper heirs of Arthur. The paint job is certainly Tudor, but dendrochronological dating of the timber indicates that it was made earlier in the middle ages, possibly at the behest of either Edward I or Edward III, both of whom appropriated the imagery to their own kingship. | |||

| I think the introduction to The History of the Kings of Britain, where he refers to the book, is interesting. He mentions Gildas and Bede, but claims to have found nothing written about Arthur or the other early kings whose deeds have only been handed down by people who had simply their memory to rely on. Then he claims to have been presented with the book, which sets it all out in an orderly narrative. I think he is confessing that he is converting oral legend to written authority, but I don't know anything about ancient Welsh sources, I'm just looking at what he said. | |||

| Not everybody approved of Geoffrey of Monmouth's creative approach. Way back in the 12th century his work was derided by the chronicler William of Newburgh and by Giraldus Cambrensus, or Gerald of Wales. The latter was an author of an entirely different approach. In his works on Wales and Ireland, history is confined to the sparest of outlines derived from annals, while the detail is reserved for his personal observations and oral tales from the native inhabitants. His work belongs more to the genre of proto-anthropology or travellers' tales than history. | |||

| The work was translated into various vernaculars, including Welsh, French and English. These are often referred to as Brut chronicles, after Brutus, the imaginary grandson of Aeneas and supposed founder of the British monarchy, where the story begins. The Brutus/British relationship is one of those spurious etymologies so beloved of medieval authors. |

|

||

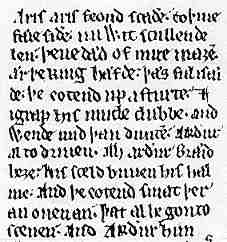

| Segment from an early 13th century copy of Layamon's Brut, an English verse paraphrase of the original (British Library, Cotton Caligula A ix, f.155). (From New Palaeographical Society 1906) | |||

| The section above describes a fight by King Arthur with a giant near Mont St Michel. The English of this date is still a foreign language to us today. | |||

| In true chronicle tradition, the Brut itself fed back into the established corpus and became the starting point for continuing chronicle or annal history. | |||

|

|||

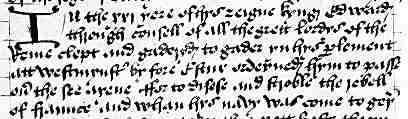

| This segment is from an early 15th century Brut Chronicle (British Library, add. ms. 33242, f.141). The chronicle is carried into the reign of Richard II. This section describes events of the reign of Edward III. By permission of the British Library. | |||

| The University of Michigan displays some leaves from a 15th century copy of the Brut Chronicle on their Brut site. | |||

| However, something else happened here. From the late 12th century onward the story of King Arthur became the basis for a new form of written text, produced for wealthy lay people for their entertainment and delight. The romance did not pretend to be other than a work of fiction, and French authors from Chrétien de Troyes onward introduced new stories and new characters, such as the knight Lancelot, into settings that were not of the ancient British past, but of the high middle ages. German and English Arthurian romance followed, but that is another story. (See the section on Romance for a continuation of this part of the story.) | |||

| Geoffrey of Monmouth presented myth as history. His history then fed back, on the one hand, into the sober historical recording of chronicles and, on the other, into a newly developing genre of fiction. He was a literary anarchist. In the 16th century the historians Polydore Vergil and William Camden had harsh things to say about Geoffrey's history, but by then it had become embedded in the mythology of Tudor kingship. Arthur was there to stay. If he didn't exist, somebody just had to invent him. | |||

| Meanwhile, the traditional form of chronicle continued to evolve. | |||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||