|

|

Histories,

Chronicles and Annals (4) |

|

In

the later middle ages, monks were still learned and literate, but monastic

communities were less enclosed from the world. Abbots went to parliament

and monasteries built large guesthouses to accommodate increasing numbers

of travellers going about all kinds of business. After the 12th century,

monasteries became less inclined to have their members sitting down in

scriptoria

transcribing

their liturgical

books, and much more inclined to purchase them from stationers in town,

as the lay people did. The monasteries still produced their chronicles,

but the authors were much more connected to the affairs of the world. |

|

The

late medieval guesthouse at St Mary's Abbey, York, now restored, was a substantial

and commodious structure. |

|

In

the 13th century the abbey of St Albans was particularly well located to collect

the gossip and travellers' tales doing the rounds, as the abbey was just one

day's travel from London on the Great North Road. It had an enormous guesthouse,

visited by all the top people from the ecclesiastical and lay world. The chronicler

Matthew Paris provides a more vivid view of contemporary life than the monastic

chroniclers of earlier times. |

|

|

Matthew

Paris, as drawn by himself. |

|

Matthew

Paris in some ways resembles a figure from earlier centuries, as he was

author, scribe

and illustrator of his own works. Perhaps this reflects the decrease in

book copying in the monasteries, and consequent dearth of specialist scribes

and illustrators. There are three autograph

volumes of his main work, the Chronica Majora,

in existence, covering, in traditional medieval form, all history from

the Creation to the time of his death. |

|

While

the format might have been traditional, the later chronicle entries are not

dry recitations of the facts of the year. There is a sequence of stories

of violence, fraud and sexual misconduct, presented in lively form along with

his harshly critical opinions of people he did not approve of, like popes

and their legates, Franciscans, and men, ecclesiastical or lay, who engaged

in slimy politics. He evidently tried to tidy up the record before his death

and excised and erased various unflattering passages, but fortunately for

posterity, a copy of the unaltered work had already been made. |

|

The

contemporary entries, as well as the copious illustrations, give us a vivid,

if not unprejudiced, picture of life in the first half of the 13th century.

In these entries he was not writing history, but for history. It may well

also reflect the way that the written word was escaping from being a reflexive

study of its own history, and was becoming a part of broader culture. The

tales and anecdotes were no longer being left for oral performers to embellish

on the core facts, but were being recorded for eternity by the chronicler. |

|

This

need to put the stories, as opposed to the bare facts, in writing may

have sometimes led to some retrospectivity. The chronicle of Croyland

Abbey, supposedly written by the abbot Ingulphus around the beginning

of the 12th century, contains a graphic eyewitness account of a fire in

the abbey, among other things. The only trouble is, it may not have been

written until the 14th century. This, like the forged charters

possessed by some abbeys, was probably not perpetrated in the spirit of

fraud. There came a time when it was necessary to put oral stories and

corporate memory into the form of the written word. |

|

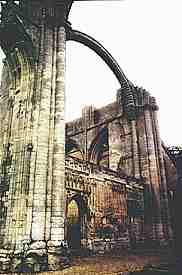

|

Part

of the ruins of Croyland Abbey. |

|

In

the 13th and 14th centuries lay literacy was increasing. This means not

only lay readers, but lay writers. Vernacular writing became common, and Latin was no longer privileged as the language

of everything that mattered. The literate traditions of constructing a

text that had lasted so long in the monasteries were no longer essential

in new experiments in lay vernacular writing. It wasn't necessary to start

a chronicle with Adam. |

|

The

most famous of these new lay chroniclers, Froissart, wrote of the period

of the Hundred Years War between England and France, during the course

of the 14th century. The early part of his work is based on an earlier

Chronicle of Jean le Bel, a knight and soldier,

while the latter part is based on his own observations and what he heard

around the traps. He has been described as more a war correspondent or

a journalist than a historian, as he was writing of contemporary events.

He revised his own work, so that there are various editions. He was also writing for history, rather than writing history. |

|

Froissart |

|

Froissart

is evidently a little flaky when it comes to the precise recording of

points of detail such as dates, places and the precise military strategy

of any particular event. His fascination for modern readers lies in the

observations of society and its moral attitudes, all from the perspective

of someone who waltzed around the royal courts when there were English

and French people, but France was not France and England was not England

as we understand those concepts today. This is the old oral storyteller,

now armed with a pen, creating pictures in the minds of his audience. |

|

A

lay chronicler did not have permanent bed and board and a supply of parchment

and quills provided by his monastic home. The lay chronicler was dependent

upon patronage, and that no doubt sometimes influenced just how and what

he wrote. Froissart had both French and English patronage and connections

at various times. This just adds a bit more fun for the modern reader

as they attempt to analyse the influences on the writer. |

|

|

Froissart

presents a volume of love poetry to Richard II. |

|

Froissart's chronicles were produced in fancy illuminated and decorated editions for lay readers, like the lavish volumes of romance which evolved and developed at about the same time. |

| Charles VI meets some armed Parisians. After a Froissart manuscript (Bibliothèque nationale ms 2644). |

| At this point there develops another twist in the convoluted relationship between fiction and history, romance and chronicle. Stories of King Arthur were not the only chronicle events which had become elaborated into heroic fiction in the form of romance. The same had occurred with stories of the deeds of Charlemagne, a man who undoubtedly existed but whose legends had gained accretions from folklore all over western Europe. The Song of Roland is a highly mythicised account of a nasty incident in which Charlemagne's army, returning from Spain after successful assaults on the Saracens, were attacked in the Pyrenees by some marauding Basques. The legend changes a nasty incident in the mountains into a heroic and tragic epic involving Saracens, presumably more worthy enemies than Basques, and a legendary hero with a magic horn. |

| The story of Roland found its way back into the chronicles, embellishing the terse historical accounts of Carolingian history with a bit of national mythology. Furthermore, pilgrims from France travelling the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostella could visit the tombs of the legendary heroes at the site of their demise as they crossed the Pyrenean pass at Roncevalles, at the monastery founded on the site. |

|

| Charlemagne finds the body of Roland, in complete 15th century armour, in a miniature by the famous manuscript painter Jean Fouquet in a copy of the Grandes Chroniques de France (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale). |

|

No

history stands outside of its society, or of the subset of society where the

author resides. Monastic chroniclers reflect their position within the formal

structure of the western Christian church. Lay writers reflect their position

in a certain stratum of society and the prejudices of their patrons. It is

as unreasonable to expect a medieval historian or chronicler to have produced

a totally unbiased account as it would be to expect a soldier in the trenches

to produce an analytical and dispassionate account of the First World War.

Anyway, it is because of their unique perspectives, biases if you like, that

these old written words are still fascinating to us today. |

previous

page previous

page |

Categories

of Works Categories

of Works |

|

|

|

|

|

|