If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Romance | ||||||

| If any single genre of literature can represent the complex, cumulative, cross-referenced and integrative nature of the medieval written word, it is that of romance. The term in modern literature has become seriously degraded, tending to relate to cheap and trashy literature concerned with relations between the sexes. For the middle ages it refers to a genre of aristocratic literature, written for the wealthy laity, which combined tales of adventure and courtly love with moral teaching. It was the literature of chivalry. It taught the aristocracy how to behave in order to maintain the social order, while entertaining them at the same time. | ||||||

| The texts of many medieval romances exist in published editions, in their original language and in translation. Many are also available on the web. Check some of the sources on the Medieval Literature links pages of this website. | ||||||

|

Before the written word became a form of entertainment, there was singing and storytelling. This continued well into the age of literacy. In fact, the formalisation of the theatre, the cinema and ultimately television were needed to kill them. | |||||

| Oral stories leave no direct traces, but there has been no illiterate culture on earth that did not have its storytelling tradition. The written record tells us of minstrels and troubadours, even what they were paid. Every so often a literate scribe (or print publisher) has written down things that were circulating in the oral tradition, from Beowulf or the Vinland sagas to legends of Robin Hood to the Child ballads so beloved of the folk song movement. These fragments cannot fully describe or map the oral tradition, but they indicate its presence. | ||||||

| The oral storyteller had a few tricks to help him survive in the halls and inns, including the use of poetry as an aid to memory. Standard expressions and phrases also helped as a memory jogger. So did a cast of stock characters around whom new stories could be woven. A noisy dinner crowd might demand another tale of their favourite character. So stories about popular characters grew organically. |

|

|||||

| The hall of Tretower manor house in Wales, set up for a television shoot. The anachronistic spray can at bottom left contained spray-on cobwebs. Well, it looks like the aftermath of a great night of song and story. | ||||||

| Stories serve a number of functions, apart from making time pass cheerfully. They can have a teaching function in relation to moral or social values. They can explore the fears and fantasies in the dark corners of the minds of listeners to allay those anxieties. Most importantly, they serve to establish an identity for a group, be it an ethnic group or a social class. The freeborn yeomen who relished the tales of Robin Hood were probably less enthusiastic about the courtly and chivalric tales which the aristocracy used to justify their position in society. As for what the peasants enjoyed around the alehouse fire, we can only guess, but my bet is that it was probably closer to Rabbie Burns than Chrétien de Troyes, despite the gap of centuries. | ||||||

|

When, around the 12th and 13th centuries, the aristocracy embraced literate culture and desired to own prestigious books, their special claim was on the stories of aristocratic life and chivalry. Very elaborate commissioned volumes told these stories in their vernacular language, which for this social class in both France and England was French. As with the oral tales, they were commonly, but not universally, in verse. Vernacular tales in the German language were also produced. These volumes were prestige goods. Their appearance and value, and their content, served to consolidate the values of this social class. | |||||

| A fight between armed and mounted knights on a castle drawbridge from a 14th century manuscript, Romance of the Holy Grail (British Library, add ms 10203). | ||||||

| These tales contained certain elements from the oral tradition. They were often in verse, and they developed many variations on certain popular themes. Some stories spawned multiple variants, addenda and new characters. The origins of some stories were from the oral tradition of folklore, but the best known cycles developed from the existing tradition of the written word. It is as if the laity were grounding their values anew in the literate tradition which had formerly been the preserve of the church. | ||||||

| The Charrette Project gives an intricate analysis of the many variants of the text in several surviving manuscript versions of Chretien de Troyes' Le Chevalier de la Charrette, showing how the stories interweave.There are also images of some of the manuscripts. | ||||||

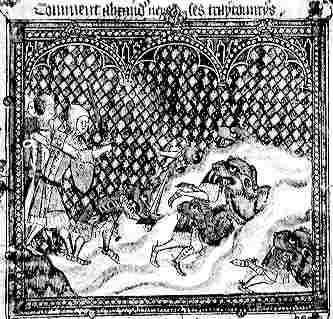

| Miniature from a mid 14th century volume of the Romances of Alexander, in French verse (Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 264, f.54). This picture shows how Alexander the Great dealt with traitors. (From New Palaeographical Society 1905) |

|

|||||

| Classical literature and history provided one source for romance literature. The adventures of Alexander the Great and stories from the seige of Troy were much used. History and fiction became intertwined. The image in the example above, while located in a distant time and place, sends a strong message on the virtue of fidelity and the fate of traitors. Other miniatures show exquisite people in 14th century dress riding elegant little horses and appearing out of fairytale castles, situating the story in a glamourised version of their own culture and social space. | ||||||

|

The stories of Alexander the Great represent material from the pagan past that was appropriated to Christian teaching. According to my friend Libby Keen, who knows Bartholomeus Anglicus' De Propriatibus Rerum forwards and backwards, the Alexander stories were much used for Christian allegory. They are also sometimes found depicted in church art. Their use in romance for the laity is just another layer of cultural appropriation. | |||||

| Alexander the Great is carried into the sky by eagles on a carved wooden misericord in Lincoln Cathedral. | ||||||

| Libby Keen's wonderful descriptions of the use of these stories can now be found in her article on Bartolomeus and his stories in the volume of essays Our Medieval Heritage, published by Merton Priory Press in 2002. | ||||||

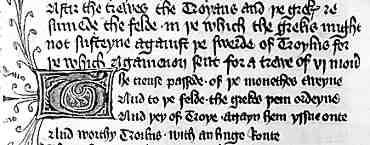

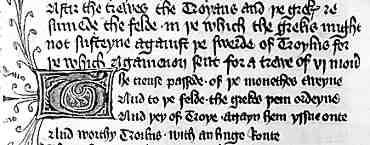

| John Lydgate's Troy Book, from the early 15th century, is a verse paraphrase in English of a 12th century verse romance in French and a Latin history of Troy. These, however, were based on phoney eyewitness histories of the siege of Troy by writers who actually lived in the 2nd and 6th centuries AD. So did this make Lydgate's work history or romance, and did anybody care? The continuing reiteration of the tale ties the middle ages to a Classical heritage and to literate tradition. The technicalities of truth or fiction in the detail are probably not so important as the concept of heritage. | ||||||

|

A segment from a mid 15th century copy of Lydgate's Troy Book (British Library, Royal 18 D II, f.105). By permission of the British Library. | |||||

| Stories from French history were also drawn on and elaborated. The historical character of Charlemagne became a mythic character of legend as tales from history became elaborated into fables and legends. The Song of Roland introduced magic horns, legendary swords, treachery, revenge and chivalric courage into what was probably a pretty ugly little episode of defending the borders of the barbarian empire. Apparently it was not the Saracens who carved up Charlemagne's rearguard on that occasion, but the Basques, but they were presumably considered an unworthy enemy for a romance. These romances provided those of Frankish descent with their origin myths, and with their justification for being a class born to rule. | ||||||

|

Roland blows his magic horn in an illustration for an early 20th century childrens' encyclopaedia. You just can't keep a good story down! | |||||

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||||