If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Histories, Chronicles and Annals (2) | ||||

| The History of the English Church and People, which was completed by Bede in 731, differed from the chronicle format in that, within the various books, the subject matter was arranged in thematic rather than strictly chronological order. It was a true history in the sense of telling a story rather than a simple ordering of events. What is a little intriguing about this is that Bede was interested in the computation of time and wrote a whole book on the subject. Ongoing debates about the mode of computing the date of Easter each year had made the computation of time a hot item among monastic scholars of the early middle ages. It was also the first work to use the birth of Christ as the benchmark for measuring time. We take this for granted, but in the early medieval period there were multiple systems for designating annual dates, depending on what major events in the religious or secular worlds were used as the benchmark. |

|

|||

|

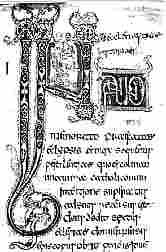

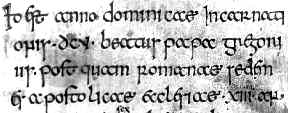

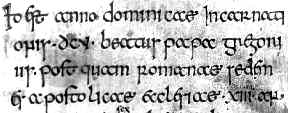

Above, a page segment with decorative initial from a 9th century copy of Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica (British Library, Cotton Tiberius C II, f.94). At left a segment from another folio of the same manuscript (f.34), by permission of the British Library. | |||

| This segment indicates that Pope Gregory died anno dominicae incarnationis dcv (in the year of our Lord 605). | ||||

| Bede's major history can be read in Sherley-Price 1960 Bede: A History of the English Church and People Harmondsworth: Penguin, or in McClure, J. and Collins, R. (ed) 1994 Bede: The Ecclesiastical History of the English People Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, or read on the web at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library Bede's Ecclesiastical History of England. If you want the full bottle on Bede in an ancient tome, try Bede 1964 Beda Venerabilis: Opera Historica Vaduz: Kraus Reprint Lyd (Originally London 1838) 2 volumes. | ||||

|

Bede evidently spent his entire life in the monastery at Jarrow. His work was not a contemporary view of the passing parade, but a scholarly study of the past from rare written sources which were supplied to him, under the great difficulties of the time, from various personages within the church. It is perhaps closer to our modern concept of a history than many works written later in the medieval period. | |||

| Remains of the monastery of Jarrow. | ||||

| Because so many of Bede's sources are now lost to us, he has become the sole authority on many aspects of Anglo-Saxon England. Certainly he wrote from a particular perspective, that of the development of the Christian church in England, but that does not make him less of a historian. He wasn't writing for folks like us, centuries hence, with a fascination for the minutiae of social history and the exotica of pagan survival in the signification of social stratification. Sutton Hoo may tell us things that Bede did not, but that does not diminish Bede. | ||||

| The annal format is strictly adhered to in that most famous of early chronicles, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The surviving manuscripts of this work are also a case study in themselves of the manuscript tradition of history. It survives in nine manuscript copies, representing several different versions, but none of them represent the original text. | ||||

| For the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle on the web, see The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle This has the stated intention to produce transcripts of all versions, but only one is done and that is not complete. It was last modified in 1994. Is there a sad story here? A compilation version from the Everyman Edition of 1912 has been put up by Berkeley. You could also try the Project Gutenberg version. Then again, you could always tackle an old fashioned book, Garmonsway, G.N. (ed.and trans.) 1986 The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle London and Melbourne: Dent. | ||||

|

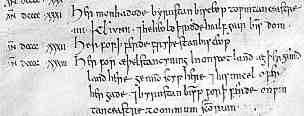

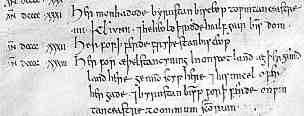

A segment from the Parker manuscript of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 173). (From New Palaeographical Society 1908) | |||

| The above example shows brief annal entries beside their dates. A rare feature of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is that it is in Old English. Chronicles in any vernacular were almost unknown before 1200, as the monastic scribes followed the literate tradition of writing in Latin. However, the extant copies are based on an original text written in the time of King Alfred, extending to the year 891. This was a time when vernacular literacy had a little florescence in England, but copies of the chronicle were maintained in English beyond the Norman Conquest, when Latin was firmly re-established as the language of the church and administration and the aristocracy spoke French. Was it just the monks maintaining a literary tradition? Were assertions of English ethnicity lurking in the cloisters? | ||||

| The text of the chronicle developed differently in various parts of the country for the additions that were made after 891. Mostly the text is very spare and annalistic, but sometimes particular episodes are enlarged or expanded. There are even a few interpolated poems. The work grew into a set of interrelated texts, rather than copies of a single text. Most of the surviving copies are written in only one scribal hand, as they represent a recopying of the entire text, but the Parker manuscript contains at least 13 different hands, variants on insular minuscule script, as the work was updated over time. | ||||

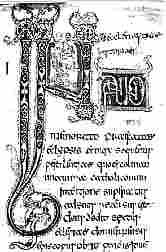

| Three different scribal hands from entries in the Parker manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. (From New Palaeographical Society 1908) | ||||

| The survival of the various versions of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle shows chronicle history as organic and evolving, rather than based on a fixed text. This is enhanced by the manuscript copying procedure itself, which cannot enforce the multiple copies of identical texts produced by the mechanical printing process. It is also another illustration of the medieval approach to literate knowledge, when a text from the past was used as the foundation for building and development of a new work. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||