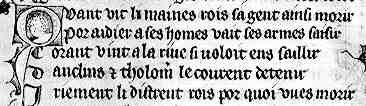

A jongleur.

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Medieval French (2) | ||||||

| During the 12th century, a tradition of production of manuscript works of literature in the French language began in earnest. The conversion of oral chansons de geste into lavishly produced and illuminated works of romance for wealthy lay readers and book owners began, and this genre thrived and grew even more complex and elaborate through the 13th and 14th centuries. Moral tales were written by clerical authors for the betterment of the souls of the laity. Songs and shorter poems were written down. Later as book ownership trickled down the social scale, stories and plays for bourgeois readers appeared. In France, religious authorities seemed to be less anxious than they were in England about the laity reading religious texts, even the Bible, in their native tongues and French language Biblical texts or Biblical paraphrases were produced. By the 15th century books of hours wholly in the French language, or with sections of French prayers, were relatively common. |  |

|||||

A jongleur. |

||||||

| Today we think of France as a nation state with clearly defined boundaries and a national language. We know that language is also spoken in parts of Belgium and Switzerland, and has spread to remote parts of the globe through colonialism. Nevertheless we conceptualise a tight relationship beween nation and language. In the medieval era it was not so tidy. The French language had many, many dialects, most of which are probably lost to us forever as they were never part of the literate tradition. France was not a neatly drawn centrally controlled state, but a mass of shifting borders, contested power relations and changing territorial control, with threats to centralised government coming from powerful magnates within and around, and a combination of battles and aristocratic marriages leading to constant disputation as to who was actually in charge of what. | ||||||

|

A little grab from a French royal signet document of 1439. Photograph ©Rob Schäfer. | |||||

| The languages of medieval France were divided into two major dialect areas known as Languedoil and Languedoc, named after the word for yes in each of them. The direct reference to them in the royal document illustrated above indicates that they had political significance as well as linguistic differentiation. The Languedoc area was basically in the south, comprising roughly the modern provinces of Provence and, yes, Languedoc and parts of southern central France. The Languedoc area retained a great many cultural and legal traditions from the days of the Roman Empire, and many ancient Roman monuments are preserved there. The pre-existing languages of this area were reportedly not Celtic. It attracted hostile attention from church and state because of supposedly being a hotbed of heresy, but the popes did move in there for a time in the 14th century. It was different. | ||||||

|

The papal palace at Avignon in medieval Languedoc. | |||||

| Languedoc had a fine tradition of oral storytelling, singing and performance, as practised by the troubadours, which developed into a regional vernacular literature of its own. Intriguingly, two venerable French tomes on French literature which I have before me (Lanson 1923, Bédier and Hazard 1923) both claim they do not discuss this literature because, fascinating as it is, it is not really French and not really part of the development of national French literature. Deary me! | ||||||

| The Languedoil of the north was divided into many loosely defined local dialects. They have been sorted into five major groups; those of Picardy, Normandy, Poitou, Burgundy and the Ile de France. Further divisions are recognised and there are no absolute boundaries that define these fluid and interconnecting languages. Gradually over time, the influence of the royal court and its patronage of writers, as well as the University of Paris, caused the pre-eminence of the Parisian variety of French, at least in literary works. However, those little documents that deal with everyday matters may appear in all manner of dialect variations and an array of historic dictionaries may be needed to decode some truly unusual words. |  |

|||||

| Completely gratuitous picture of the interior of the St Chapelle, Paris, symbol of 13th century French royal court aesthetic, culture and piety. | ||||||

|

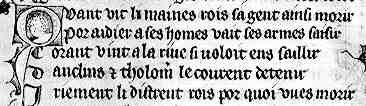

A little segment from an early 14th century verse edition of the Romances of Alexander (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodl. 264, f.54). (From New Palaeographical Society 1905) | |||||

| The above example is from a fancy illuminated book of romance in the Picard dialect. | ||||||

|

||||||

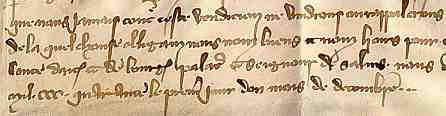

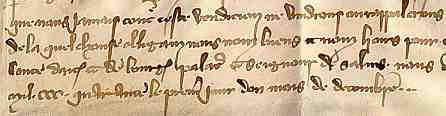

| Lower left segment of a land sale document of 1340 from Burgundy, in a private collection. | ||||||

| You should be able to read the date in the last line of the example above with knowledge of modern French, but there seem to be a few strange words here and there in other places. | ||||||

| The Languedoil dialects spread into southern France as a literary language as a result of various ructions which had to be brought under control by authorities in the north. The only corners of the country retaining languages which were not French at all were the Basque area in the Pyrenees on the Spanish border and Brittany, which retained a Celtic or Gaelic language. However, the Breton legends that were incorporated into the ever growing literary romances, including adventures of that English hero, King Arthur, were written in French. The French language and literature also spread beyond the borders of France. | ||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||||