If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Medieval French (3) | ||||

| The French language spread beyond the boundaries of France, and for those of us of Anglophonic descent, the most significant event was the Norman Conquest of 1066. The arrival of William the Conqueror's armies saw the establishment of a French speaking aristocracy in England, and for some centuries England was a bilingual country, with French as the language of the aristocracy and English that of the lower, and less literate, classes. | ||||

|

The Bayeux Tapestry depicts this linguistic assault on England. | |||

|

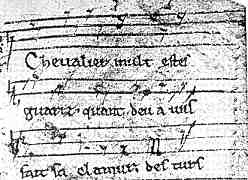

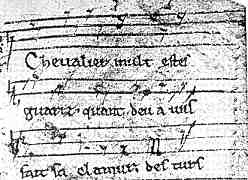

The dialect of the conquerors was not the French of Paris, but of Normandy. It is referred to as Norman French, or as it acclimatised in its new country, Anglo-Norman. The example at left is purported to be the earliest record of French song, in the Anglo-Norman dialect. | |||

| Sample from a crusading song of 1146 in the Bibliothèque d'Erfurt. (From Bédier and Hazard 1923) | ||||

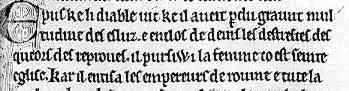

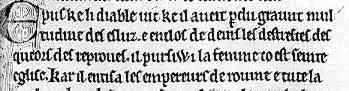

| Being the language of the aristocracy, some very fancy illuminated manuscripts were produced in this dialect, such as the Apocalypse shown below, illustrated with over 90 miniatures. Norman French was influenced by Germanic languages, the Norman aristocracy themselves being of Scandinavian ancestry. Notable is the use of letters uncommon in French such as w, and k rather than qu. | ||||

|

Little grab of text from an elaborate Apocalypse in Anglo-Norman of c.1230 (Cambridge, Trinity College Library, MS R 16.2, f.14). (From New Palaeographical Society 1904) | |||

| The Normans brought educated churchmen with them as their agents of literacy, so the language of law and government in England became Latin. Over the centuries, French gradually appeared in legal documents, and eventually English. This official French seems to have developed a life of its own, with words abstracted from English and a kind of English feel, including a fondness for brevity, in the sentence construction. | ||||

|

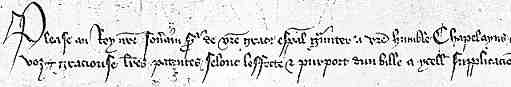

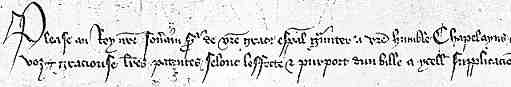

||||

| This is the left hand end of a long narrow petition in French to Henry VI from the abbot and convent of Notre Dame de Combe in Warwickshire. It dates from 1441. (London, National Archives E28/G8/18). By permission of the National Archives. | ||||

| Meanwhile, there was a movement in England in the 14th century away from Norman French and towards the French spoken in Paris as the language of an intellectual and cultural elite. The 14th century also saw the promotion of English as the main language of the country in literature, law, government and general parlance, no doubt encouraged by patriotic urges fuelled by continuing wars with France. | ||||

| Literary French also spread to other parts of Europe along with political events and a mobile aristocracy, such as the dukes of Burgundy in Flanders or the Norman kings of Sicily. French literary works were produced in the Holy Land and in Italy. Savoy in northern Italy was French speaking. | ||||

|

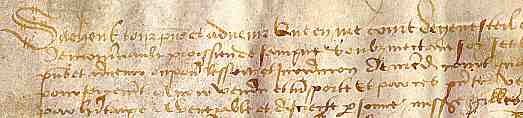

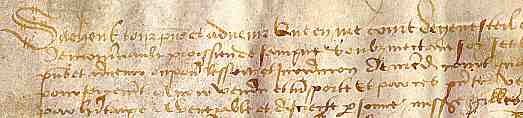

||||

| The top left corner of a legal document of 1516 in French from the Savoy area, from a private collection. | ||||

| The reading of medieval French has the same problems as reading medieval English. There is much strange vocabulary, varying between multiple dialects. Spelling is both different and very unstandardised. Furthermore, those iconic elements that the French claim as an essential aspect of their cultural heritage, accents on letters, are not there. Where modern French would use a circumflex one is likely to find the letter s. Acutes, graves and cedillas are are absent. The apostrophe is also not used when the e of le is dropped to merge it with a word beginning with a vowel, so that what would be written in Modern French as l'abbé may be rendered as labbe. | ||||

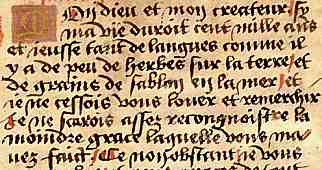

|

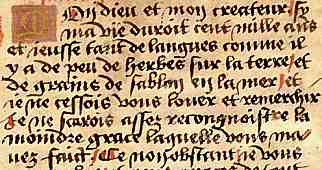

Segment of a French prayer of the late 15th or early 16th century, from a private collection. | |||

| In this segment from a book of hours, the language is not difficult compared to modern French, but there is not an accent in sight. | ||||

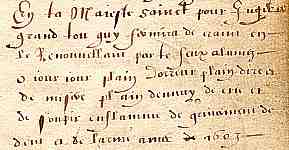

|

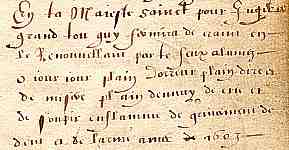

Prayer added to the flyleaves of a late 15th century book of hours, from a private collection. | |||

| This dated example of French from 1603 also is devoid of accents. | ||||

| Fortunately for us today, there are many dictionaries of historic French available both in ancient paper editions, and more recently online. If you think some weird word looks so strange that it could not possibly exist, you just might find that it does. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||