If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Writs and Mandates | ||

| The subject of how to define a writ has nearly caused domestic discord at our place, as the term changed in usage as regards English documents over the course of the later medieval period. Being a word of Anglo-Saxon origin, it only refers to English documents in a strict and literal interpretation of the term. However, documents with similar function were issued from the royal and papal courts of Europe, referred to as mandates or mandamenta. | ||

| An earlier section (See Anglo-Saxon Charters and Writs) described how very formal Latin diplomas were replaced by simpler vernacular documents around the time of Edward the Confessor. These are known as writs, and are ancestral to both the formal Latin charter and the documents known as writs in the later middle ages in England. While the charter, very ceremoniously and formally addressed to many people, was a legal document granting land tenure or some other privilege in perpetuity, the writ became simpler document, addressed to fewer people, of whom the most important was likely to be the sheriff who was charged with ensuring that the instructions in the letter were carried out. |  |

|

| Seal of Edward the Confessor, supposedly the inventor of the English writ. | ||

| The writ of the later middle ages was therefore an official letter from royal authority, either bestowing a privilege or issuing an instruction. While it was simpler in appearance and construction than a charter, it retained certain formal characteristics of that class of document. It was written on a single sheet of parchment, on one side only, was delivered open and was ratified with the royal seal. Like a charter, it was a public proclamation. | ||

|

||

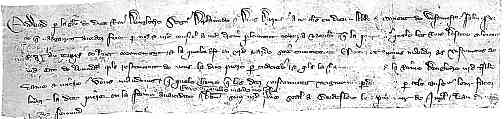

| A writ of Edward III to the abbot and convent of Westminster, of 1328 (Westminster Abbey, Muniments, Coronation No II). (From New Palaeographical Society 1910) | ||

|

||

| The beginning of the above document, showing the inscription or title, which reads Edward par la grace de dieu Roi Dengleterre. | ||

| The somewhat scruffy and damaged document illustrated above is of some historical significance. It is a writ issued under the privy seal to the abbot and convent of Westminster ordering them to deliver to the sheriffs of London the stone on which the kings of Scotland sat at their coronation so that it may be sent back to Scotland. The document is written in a cursive script in the vernacular, but at this time the vernacular of the kings of England was still French. The seal is missing. The stone in question is the famous Stone of Scone that sat for centuries under the coronation throne in Westminster Abbey and it only took from 1328 to 1996 for the order to eventually be carried out. |  |

|

| The coronation chair with the Stone of Scone tucked neatly under the seat. | ||

| A summary of the history and legends surrounding the famous slab of stone can be found at Lia Fail: The Stone of Destiny website. As the site shows, myth and politics continue to be a feature of the history of the stone. | ||

| Carolingian royalty produced documents of similar character called mandamenta, or mandates, for the issuing of orders or regulations. They disappeared from continental Europe at the end of the Carolingian era, to reappear around the beginning of the 12th century when administrative documents were proliferating in all areas. The same term is used for the less formal variety of papal bull when it was used for issuing orders or instructions. | ||

|

||

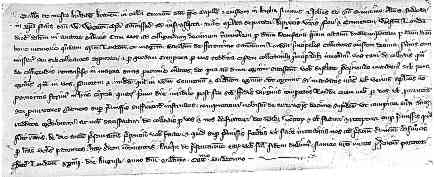

| Mandate of 1311 by William de Testa, archdeacon of Aran and papal collector in England to the prior and convent of Westminster (Westminster Abbey, Muniments, No. 12375). (From New Palaeographical Society 1910) | ||

| The beginning of the above, reading uillelmus de Testa Archidiaconus Aranensis in ecclesia Conuonensi domini pape Capellanus ...... | ||

| The above example is written in a cursive script without elaborate calligraphic flourishes or peculiar headings. Being a church document, it is in Latin. Lesser formality did not extend to using the vernacular. There is a damaged seal, but it is not shown in the photograph. The document is of some significance, as it informs the recipients that if they do not pay up their arrears on the tithes imposed by Pope Boniface VIII they will be subject to excommunication and interdict. Serious stuff. | ||

|

|

||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||