If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Writs and Mandates (2) | |

| The term writ is derived from an Anglo-Saxon word which simply means a letter. Under Edward the Confessor it developed a very particular meaning and stylised form and level of formality. There are references to letters from earlier Anglo-Saxon kings, but none of them survive so we have not the foggiest idea of what the term refers to in the earlier period. In the later medieval period, the whole royal administrative process diversified and became more complex. The writ was one of a number of documents under royal authority, each with their own particular form and function, which included charters, letters patent, letters close and warrants. This is what my resident (late) medievalist refers to as a "proper" writ. I'll leave him to argue that one out with the Anglo-Saxonists. | |

| Compared to the high flown language and pompous presentation of the formal charter, the writ became both scruffy and terse. Some give the impression of being not so much a grand public proclamation as a snarled order, metaphorically growled from the side of the mouth. | |

|

|

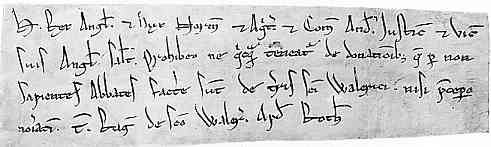

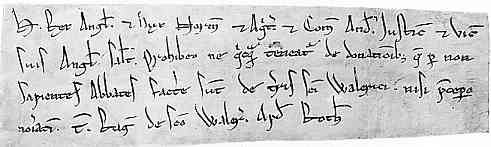

| Writ of Henry II, of 1156-1166, to the justices and sheriffs of England (New College, Oxford). (From Salter 1929) | |

| The writ above has a title, address and salutation, as well as a witness clause, just like a charter. However, it is all very brief and to the point. It prohibits unwise abbots from making gifts of the lands of St Walery unless he, the king, commands it. And that's that. The charter hand of this period tends to look spiky and irritable at the best of times, but this does look rather as if it has been scribbled off without too much care and attention. There is only one witness. The damaged seal is not shown in the photograph. I have a foolish mental picture of King Henry barking his instruction to a flustered chancery clerk who desperately had to come up with a Latin translation for the 12th century equivalent of "bloody stupid abbots", and who managed non sapientes abbates. I beg your pardon, I was just enjoying myself again. | |

|

|

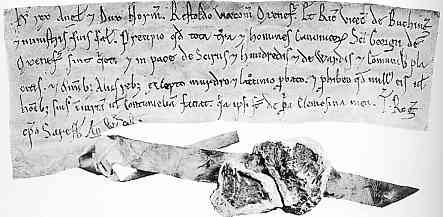

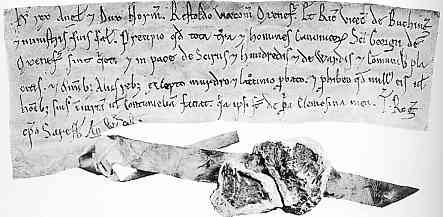

| Writ of Henry I to the sheriffs of Oxford and Buckinghamshire (Christ Church, Oxford). (From Salter 1929) | |

| The above example is addressed to two individuals, Restoldus sheriff of Oxfordshire and Ricardus sheriff of Buckinghamshire, commanding them to observe the liberties granted to the men of the canons of St George's. Once again it is brief and to the point. The relics of the seal are attached to a strip cut horizontally from the bottom of the parchment, with a second strip to secure the folded document, entirely in the manner of the Anglo-Saxon writs from which the form derives. | |

| It is intriguing that the excellent old books of manuscript facsimiles which have supplied so many of the examples for this website rarely show these simpler documents, preferring to illustrate the grander types of charters. The author of the volume from which these derive actually apologises that the number of early documents in Oxford is so few that he has had to use all those available, even little humble specimens. Yet these are just as much part of the history of literacy and the development of literate government as the magnificient examples. | |

| As with a charter, a writ was not necessarily addressed to the beneficiary, but was often addressed to officials who treated it as a public document. Some writs just disappeared out into the blue to be dealt with and were seen no more. However, a process developed whereby officials like sheriffs were obliged to present the writ, usually before a royal justice, to ensure that it had been received and acted upon, and it was returned for filing. By the time of Henry II the chancery was churning out multiple copies of standard writs for certain purposes. These just required filling in of the appropriate names and the attachment of the seal. Standard government forms go back that far, but it must have been a hilarious job writing out the multiple copies by hand. |

|

| By the 13th century, the recipients of writs could pay to have them entered on the utterly modern and innovative system of chancery rolls, to ensure that the contents were archived and any ensuing benefits from the writ could be confirmed at a later date. One assumes that this must leave some bias in the surviving record, as recipients would be more inclined to part with their hard earned cash to record a benefit in a friendly writ than to enshrine forever the fact that the king had sent them a few harsh words on some matter or other. | |

| The production of writs was not confined to the monarch. The magnates of the aristocracy also used the form, and sheriffs sent instructions to their own officials in this way. The terminology of these documents, as we keep discovering, becomes very entangled and the term writ applies to the form of words in the later middle ages. The mode of delivery, either open for public proclamation or closed for private reading, means that writs can also be classified as letters patent or letters close. At some stage in the scheme of things, letters between private individuals just become letters. | |

|

|

|

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|