If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Vernacular Bibles (3) | ||||

| In the 13th century, the church was actively engaged in fighting heresy, notably the Cathar or Albigensian heresy based in southern France. The nature of this heresy was that the adherents believed in a dualistic universe, with a spiritual universe created by a good principle, and the material world created by an evil principle. This challenged the absoluteness of God. To combat such notions, people were required to be guided in their interpretations of the scripture by those authorised to do so, the literate Latin clergy. The expansion of the preaching orders of mendicant friars, such as the Dominicans and Franciscans, got the word out to the people. | ||||

| Bible stories were also being presented to the people in the form of pictorial narrative. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the magnificent 13th century stained glass windows of stunning buildings such as Chartres Cathedral or the Sainte Chapelle in Paris expanded their iconographic repertoire from monumental depictions of saints, martyrs and church fathers to include narrative scenes from Biblical stories in brilliant, glowing roundels. People were seeing the Bible, but what they were seeing was the stories, not the complex interpretation of theological concepts. |

|

|||

| Scenes from the Old Testament story of Joseph, from the stained glass windows of the north aisle of the nave of Chartres Cathedral. | ||||

| Also at around this time, the culture of the manuscript book was extending from clerical readers, literate in Latin, to wealthy lay patrons. Luscious and exquisitely illustrated Latin Psalters were commissioned by aristocratic lay people for the use of their private chaplains, and for posh display. A form of lavish Bible picture book known as the Bible Moralisée was produced for some highly aristocratic patrons. Only minimally captioned in either Latin or French, the imagery linked Biblical narrative to moral issues of the day. Images were not just the Bible of the poor or illiterate. Visual culture was also for the wealthy and cultivated, and the significance of the Biblical stories was being interpreted for church visitors or book owners through pictures. | ||||

| More detail on the iconographic scheme of the Bible Moralisée, as well as some wonderful illustrations, can be found in de Hamel 2001. Some miniatures from one famous example are displayed on the site Maciejowski Bible. | ||||

| The so-called Bible Historiale took this principle into the realm of vernacular literature. In the 12th century one Petrus Comestor produced a Latin work called the Historia Scholastica, comprising narratives from the Bible. This was translated into French in the late 13th century by Guyart de Moulins, and presented with some additional material from a mid 13th century French translation of the Bible. This work appears in numerous elegantly illustrated manuscripts over several centuries. | ||||

|

This page has images in grisaille on a coloured ground. The miniatures at the top show several episodes from the life of Solomon. The French text is in a Gothic textura script. The lamb and the lion in the lower border may be regarded as having Christian allegorical meaning, but a bunch of very 14th century monkeys are also disporting themselves in the frame. The elaborate foliate border with birds gives this all the attributes of a fine quality manuscript of its time. | |||

| A leaf from a Bible Historiale of 1357 (British Library, Royal 17 E VII, first page of Volume II). (From New Palaeographical Society 1909) Click on image for a larger version. | ||||

| The vernacular text, as well as the illustrative program, may have given inspiration for preaching by those clergy active in the field. After all, there's not much use preaching in Latin. The emphasis on narrative rather than theological interpretation meant that these works were also relatively safe for ownership by wealthy lay readers. While the laity could own a Bible, they were not being given access to some of the more tricky bits which could lead to the development of wrongheaded notions. | ||||

|

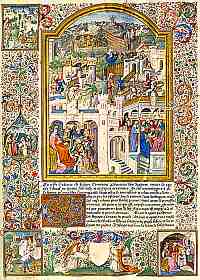

This incredibly elaborate page, of the beginning of Genesis, belongs to a two volume Bible Historiale which belonged, according to two inscriptions at the beginning and end, to no less a personage than the Duc de Berry. The inscription at the end is in his own hand. The page includes an image, at the top, of the Holy Trinity in its standard medieval depiction, with the Father suppporting the crucified son and the Holy Ghost as a dove. | |||

| Bible Historiale of the early 15th century (British Library, Harley 4381, 4382, Vol.i, f.3). (From New Palaeographical Society 1911) Click on image for a larger version. | ||||

|

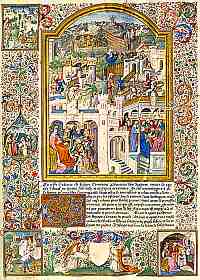

A splash of colour gives us a hint of the production values of these volumes. This late example also shows how the story is told in intricate pictorial narrative as well as in words. This page shows the people of Israel held in servitude, from the book of Exodus. Many of the intricate images are derived from the way the story was depicted in the Mystery Plays, from around the 14th century another way in which Biblical narrative was presented to the people. | |||

| Miniature from a Bible historiale of around 1420 (Bibliothèque nationale, ms 20065 du fonds français). (From Bédier and Hazard 1923) Click on image for a larger version. | ||||

|

Lower half of a page from the Holkham Bible Picture Book of the early 14th century, representing the Miraculous Draught of Fishes, from a facsimile. | |||

| The above example represents a different vernacular text for what is basically a picture book of the Bible. The pages are largely taken up with tinted drawings from Bible stories, with a brief text which is partly verse, partly prose. It includes considerable apocryphal matter, especially on the infancy and childhood of Christ. This fleshing out of the narrative of Christ's earthly origins also appears in stained glass windows at this time. Intriguingly, while produced in England, the language is French, presumably indicating aristocratic patronage. | ||||

|

A single book of the Bible that was selected for vernacular and pictorial presentation was the Revelation of St John, known as the Apocalypse. The mad imagery in the text lends itself to pictorial presentation, and in the 13th century thay had one of their attacks of feeling that its time was imminent. While there are no overt moral messages in the text, in the sense of instructions on how to behave, the general sense of impending doom and chaos was probably deemed to be good for a potentially errant reading populace. Nobody would want to be classified as a heretic with that in the offing. | |||

| Apocalypse in French of c.1230, with commentary and 91 miniatures (Cambridge, Trinity College Library, MS R 16 2, f.14). (From New Palaeograhical Society 1904) For a groovy colour version of this illustration, see de Hamel 2001. It has lots of red and black and looks very scarey. | ||||

| While large numbers of the Latin Vulgate Bible were being produced in the 13th century for the expanding clerical groups, the fancy vernacular volumes for the laity might be seen as a prettying up, but dumbing down, of this most complex and fundamental Christian text. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||