If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Vernacular Bibles (2) | |||||

| The origins of English vernacular Bible texts are also tied in with the mythology of kingship. King Alfred, in the late 9th century, is depicted as having united various Anglo-Saxon tribes into a single Christian nation, now defending itself against the incursions of nasty, pagan, barbarian Danes. As with Charlemagne, the official mythology demanded a ruler both brave and cunning in battle, and wise, scholarly and literate. | |||||

|

A schoolbook image of Alfred, disguised as a minstrel, spying in the Danish camp. Hey, the guy could sing and play the harp too. What a king! | ||||

| The myth has it that Alfred himself translated the Bible, along with various other significant religious texts. Certainly some important Latin texts were translated into Old English by folks learned in both Latin and their native tongue. There is no complete Bible text in Old English. Still, if a scholarly full time monk like Jerome took decades to translate the Bible into his native tongue, it would be a bit of a tall order for a fighting king with a part time interest in learning, and no known upbringing in the finer points of Latin literacy and Biblical scholarship. | |||||

|

|||||

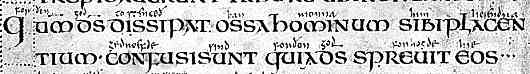

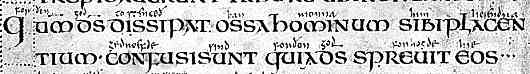

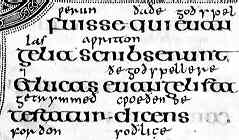

| Two lines from the Vespasian Psalter, of the early 8th century, with mid 9th century Old English gloss (British Library, Cotton Vespasian A1, f.53), by permission of the British Library. | |||||

| One form of vernacular text is exemplified by the earliest surviving translation of a Biblical text into Old English. The Vespasian Psalter contains the text of the Psalms in Latin, written in an uncial script, with a later interlinear gloss in Old English. Spot the word god in two places in the above illustration. This is not a grammatical translation, but more of a running glossary, as it simply follows the Latin word order. It might be regarded as providing a series of prompts for those Anglo-Saxon clergy whose Latin was perhaps less than perfect. | |||||

|

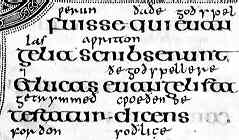

Another famous example of this type is the Lindisfarne Gospels. The 10th century Old English gloss was written by a monk of Lindisfarne, Aldred, who told us all about it in the colophon to the book. Another interlinear translation of the book of Matthew, in a manuscript known as the Rushworth Gospels, is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. | ||||

| Segment from the Lindisfarne Gospels (British Library, Cotton Nero D IV, f.5v), by permission of the British Library. | |||||

| King Alfred did use an Old English translation of the ten commandments and other sections of Exodus dealing with laws as a prefix to his own code of laws. The story goes that he also started work on translating the Psalms. A verse paraphrase of the Psalms does exist in a single manuscript, but apparently not the work of single translator. This is all starting to sound like a familiar story of medieval kingship. Charlemagne had liked to style himself as King David, according to his biographer, Einhard. The association of Biblical law with Anglo-Saxon law provides strength by association. Tying the language of the Bible to the language of laws and kingship firms the association. It still does not require vernacular literacy to extend beyond the cloister. Monks worked for kings. | |||||

| The other form of Old English Biblical text was not so much translation as paraphrase of certain chapters and stories from the Bible. The earliest example of this is recounted by Bede, and has certain mythifying elements, even if based on an underlying truth. In the late 7th century an illiterate herdsman called Caedmon, working as a labourer in the abbey of Whitby, could not sing or play the harp, and so retired to the stable in embarrassment when it was his turn to perform for the other abbey servants. There he had a divine vision that enabled him to create poems from the stories of the Old and New Testaments. | |||||

|

A view of Whitby, with the ruins of the much later abbey buildings above the town - a most romantic and historic place for a divine vision. | ||||

| Caedmon's original inspired poem survives in a Latin version of Bede and in two different Anglo-Saxon dialects. A 10th century manuscript, now in the Bodleian Libray, containing poems on Genesis, Exodus, Daniel and other religious themes, has been partially possibly identified with the works of Caedmon, along with works of later writers. The fact that this codex contains vernacular verse of several different origins indicates that vernacular poems on Biblical themes were an accepted form of the time, suitable for collecting together for either preaching or religious contemplation. | |||||

| A page from the Caedmon manuscript (MS Junius 11, p.46), showing an angel guarding the gates of Paradise, is displayed by the Bodleian Library. A modern English translation of the text of the manuscript can be found on Berkeley University's Online Medieval and Classical Library. | |||||

| Legend has it that Bede himself was working on an English translation of the Gospel of St John when he died. If this is true, it does not survive, and Bede was famed for his prodigious output of history, religious commentary and poetry in Latin, not the vernacular. The death of Bede is another incident that has been subjected to the mythmaking process. |

|

||||

| A modern take on Bede on his deathbed, dictating the gospel of St John to an exquisite blonde Anglo-Saxon youth. I love old schoolbook images! | |||||

| From the late 10th or early 11th centuries, there survive seven manuscripts containing a version of the four gospels in the West Saxon dialect. From the same period, there survive two composite vernacular versions of the first books of the Old Testament, referred to as the Old English Hexateuch and the Old English Heptateuch as one contains the first six books and the other the first seven. Parts of this work appear in several other manuscripts. Apart from Genesis, most of the books are heavily edited or paraphrased. It seems that by this time vernacular Bible texts, like married priests, were acceptable and even desirable in the Anglo-Saxon church. | |||||

| During the 10th century there were reforms carried out in the Anglo-Saxon church under the influence of the bishops Dunstan, Ethelwald and Oswald, replacing the secular clergy of the great churches with Benedictine monks and attempting to restore papally approved Catholic order to the establishment. Then, if course, in 1066 a little event occurred that was as significant for the church as for the lay communities of England. William the Conqueror brought in his Norman bishops to oversee the church. Latin again became the official language for all matters religious and William, another ruler of mighty personal reputation, stamped his linguistic mark on the church. English Biblical texts would not reappear for some time. | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||||