|

|

The

Bible |

|

The

fundamental literature of medieval Christianity was the Bible,

the Old Testament

comprising the books of the history of the Jewish people in the period

before Christ's birth and the New

Testament telling the life, death and resurrection of Christ and the

subsequent works of the apostles and early converts. Until around the

4th century AD, the Bible was the only formal liturgical

book in use in the Christian church. |

|

|

A

Biblical scene depicted in stained glass in the church of All Saints,

Pavement, York. The apostles watch Christ ascend to heaven, his feet dangling

from the sky while his footprints remain on the hill top. It is included

here simply because I like it so much. |

|

The

general form and content of the Bible had been established in the early

centuries of Christianity. The medieval Bible of the Western or Roman

church was in Latin, the Vulgate

version as translated and revised by St Jerome in the late 4th and early

5th centuries. As various Latin versions of the Bible had been in circulation,

Jerome translated his versions anew. The Gospels were translated from Greek sources, while the complete Old Testament was

translated from the Hebrew. |

|

Until

around the 12th century there were few complete Bibles. Various segments

of the Bible were reproduced as separate volumes. Some of the most famous

early manuscripts are Gospels, containing only the accounts of the life

of Christ, the books of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. |

|

|

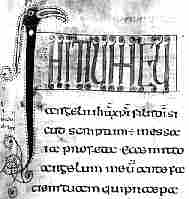

Section

of a page from an early 8th century Gospel, probably written at Lindsifarne

(British Library, Royal 1 B VII, f.56), by permission of the British Library. |

| The above example was probably more of a working service book and less of a display volume than the more famous Lindisfarne Gospels. |

|

Other

segments produced individually included the Acts of the Apostles and the

Psalms. The Book of Revelations, when produced on its own as a volume,

was termed an Apocalypse.

The wild imagery from the Book of Revelations lent itself to depiction

in amazing miniatures. |

|

|

|

Apocalyptic

visions from an early 13th century volume (Cambridge, Trinity College

Library, MS R 16.2, f.14). |

|

|

|

The

woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of

stars, who travailed and brought forth a man child, is one of the visual

wonders of Revelations depicted in the windows of St Michael Spurriergate

church in York. |

|

The

various books of the Old Testament were produced individually, or several

together. The first five books of the Bible in a single volume, for example,

was known as the Pentateuch. |

|

Various

books of the Bible had been produced in Old

English in late Anglo-Saxon England, but the use of Latin was restored

under the combined effects of 10th century reforms and the Norman Conquest.

Paraphrases or metrical verse versions of certain books of the Bible were

produced in the vernacular,

in French or English, from the 13th century. |

|

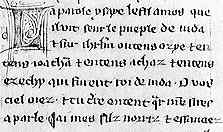

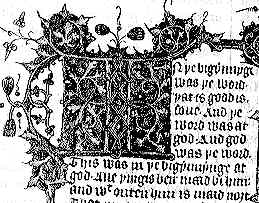

Segment

from a French Bible Historiale of the early 14th century (British Library,

Royal MS I A xx, f.66). |

|

In

the 14th century the so-called Wycliffite translations into English appeared

in the form of a plain translation which was comprehensible to the laity.

In an imposition of church authority against the Lollard heresy, the use

of these was forbidden in the early 15th century. As the majority of the

population was not competent in Latin, the original source material of

Christian teaching was only truly accessible to the educated clergy, who

interpreted it for the people through preaching and lessons. |

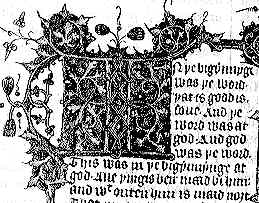

Section

from a Wycliffite Bible.

|

|

Up

into the 12th century Bibles, or the components thereof, were large and

imposing volumes, often grandly decorated, designed for liturgical use.

They sat on a lectern and were used for readings in church, as objects

of public performance. The reproduction of these works by manual copying

was undertaken in monastic scriptoria.

Sometimes the basic text had an accompanying commentary, known as a gloss,

built into the design of each page. Such weighty works were often divided

into several volumes.

|

|

In

the 13th century there was a great proliferation of small, portable Bibles

produced by commercial manuscript copyists rather than by monks. These

were the first Bibles to be systematically set out with books in a standard

format and with the text divided into numbered chapters. The Gothic

script of these volumes was tiny, simplified and neat. |

|

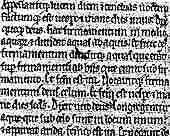

The

minute compressed script of a 13th century Bible (British Library, Burney

MS 3). |

|

In

the 14th and 15th centuries these were overtaken in production again by

large Bibles designed for public use in church; weighty and significant

ritual objects in their own right. By the late 15th century these could

be reproduced by the printing process and were one of the first works

in production.

|

|

Early

Bibles and Gospels  |

|

Great

Big Bibles  |

|

Little

Tiny Bibles  |

|

Vernacular

Bibles  |

|

Categories

of Works Categories

of Works

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|