If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Church Liturgy (2) | |||||

| A similar process of compilation occurred with the texts required for the celebration of divine office, the daily round of choir services performed by monastic communities and also by the secular clergy. The offices comprised the night office, Matins, and the seven day hours, Lauds, Prime Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline. The choir services comprised psalms, hymns. lessons, antiphons, versicles and responses. The content varied with each service in the cycle and according to the church calendar. The conduct of divine office followed the original prescriptions laid down in the Rule of St Benedict. |

|

||||

| The night stairs in the south transept of Hexham Abbey, where the monks came into the church to celebrate the night office. | |||||

|

The antiphons and responses of the choir were produced in the antiphoner. The psalter contained the Psalms, usually arranged in the original Biblical order, but occasionally in the order in which they were performed during divine office. The various other components of the readings and chants were compiled together gradually from the 11th century. Highly abbreviated versions of the complete round of services were produced in which the psalms were omitted and various other components were indicated only by their first words. The priest, performing the cycle every day, was supposed to know them by heart. This was called the Brevaria divini officii. Eventually the text was included in full, but the term breviary remained. | ||||

| The medieval choir stalls of Ely cathedral, where the monks performed the divine office. | |||||

| Columbia University Library displays a 12th century Italian breviary with the older style of muscial notation (Plimpton MS 33 (frag.) recto). A leaf from a 14th century French breviary is displayed by the Wallace Library, Rochester Intitute of Technology. A full study of a psalter can be found at The Burnet Psalter site, as well as on the St Albans Psalter site, both from Aberdeen University. | |||||

| The antiphoner remained a separate volume for the use of the choir, as did the psalter which often contained extra components such as the calendar, the litany, the penitential psalms and the office of the dead. While some breviaries and psalters were elaborate prestige objects owned by members of the aristocratic laity, they were liturgical books and most likely used by their domestic chaplains rather than for private devotion. |

|

||||

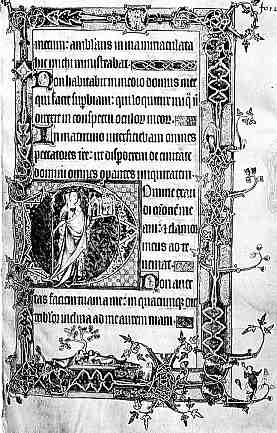

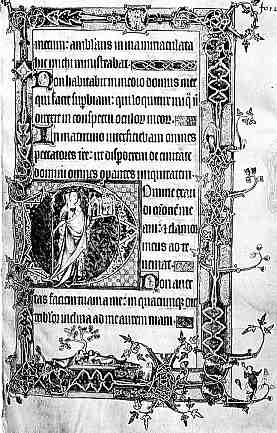

| Leaf from a highly decorated 14th century psalter with an elaborate historiated intial and border (From Douai. Bibliothèque Publique, MS 171, f.127). (From New Palaeographical Society 1903) | |||||

| A 13th century antiphoner is displayed in detail by the State Library of South Ausralia. The Wallace Library, Rochester Institute of Technology, displays a leaf from a very fine 15th century Italian antiphoner with the more modern medieval style of musical notation. Columbia University shows a 12th century German psalter (Western MS 49 (frag) recto) and a 14th century psalter, probably from England (X223.2/B47, ff.10v-11). | |||||

|

|||||

| Processionals contained prayers, hymns and litany for use during processions around the church on major feasts such as Palm Sunday. | |||||

| Columbia University displays a 14th century processional for Franciscan use, from Flanders (Plimpton MS 34, f.18). | |||||

| In the early medieval period there was a range of small volumes containing various specialised services such as the sacramental services of baptism, marriage, extreme unction, as well as services for the visitation of the sick, the burial service and various blessings. These were compiled together, along with certain elements from the old sacramentary which did not refer to the mass, to form the ritual. This essentially contained all the services a priest needed which were not in the missal or the breviary. This was the least uniform of the medieval liturgical books and varied from diocese to diocese. | |||||

|

A bishop performs a marriage in a 16th century stained glass window in the church of St Michael-le-Belfry, York. | ||||

|

|

|||||

| |

|||||

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||||