If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| The Psalter | ||||

| The psalter was the ancestor of all the books of the divine office, including that later medieval invention for the laity, the book of hours. Psalters came in plain versions for daily use, as well as highly elaborate illuminated versions with miniatures, historiated initials and hierarchies of headings. The nature of historical preservation is such that there is a greater proportional survival of the fancy prestige volumes, which have been curated for centuries and less used, than for the day to day service books which were most likely used to death. | ||||

| An examination of the psalter is a fascinating exercise, as it becomes a study of the nature of medieval text and reading. The psalter contained texts for declaiming aloud, and was chanted repeatedly by the clergy in the course of their liturgical duties. It was a text to be learned by heart. |  |

|||

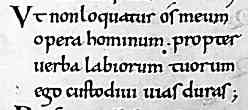

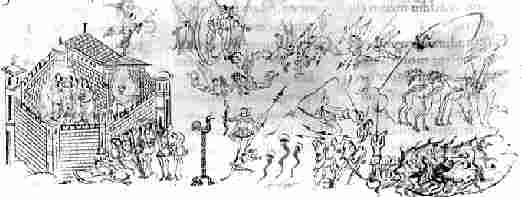

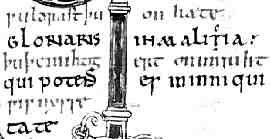

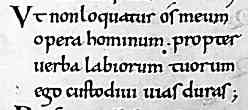

| A segment from the Harley Psalter, an 11th century copy of a 9th century work, and below, an illustration from the work. (British Library, Harley 603), by permission of the British Library. | ||||

|

||||

| The Utrecht Psalter, a work produced near Rheims around 820, was the model for the Harley Psalter illustrated above. Although the original was written in uncial script, unlike the Caroline minuscule of the copy, it contained a series of coloured line drawings illustrating the text, which were faithfully duplicated in the copy. Illustrations were not just for decoration, but served as aids for remembering the text. No matter how clearly the text was written, the work was performed in gloomy buildings by flickering candle light. Coded graphic elements were part of psalter design from the early days. | ||||

|

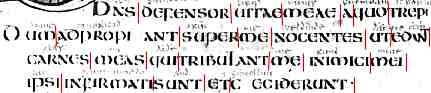

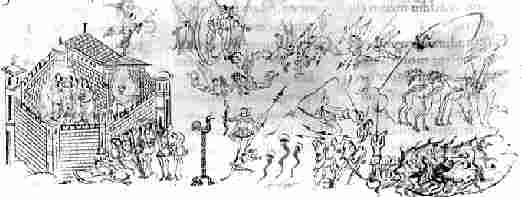

Detail from the 8th century Vespasian Psalter (British Library, Cotton Vespasian A1, f.31), by permission of the British Library. | |||

| The Vespasian Psalter, produced for the ancient monastery of St Augustine, Canterbury, contains some of the earliest examples of historiated initials. Each one provides a visual marker for the text of the following Psalm. The necessity for this visual cueing is accentuated by some idiosyncrasies of the written text in the form of quite aberrant word spacing in the gracious uncials of the Latin text, and an Anglo-Saxon gloss in tiny pointed insular minuscule above the words. | ||||

|

Text with gloss and digitally added word spacing lines from the above example. | |||

| The Old English text was not for performance of the liturgy, which was always in Latin, but for aiding comprehension among a monastic community only partially literate in Latin at this time. Both scribes and performers were still on the learning curve with their Latin literacy during this early era. | ||||

|

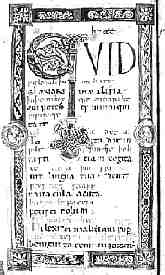

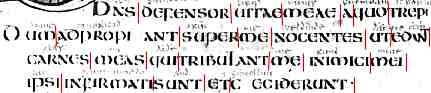

The image on the left shows a page of the Winchcombe Psalter (Cambridge MS Ff 1.23, f.88v), by permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library and the British Library. The lower image shows a detail of the text. | |||

|

||||

| The above example from the 11th century shows the vernacular text now incorporated as part of the page design rather than added as a gloss. The initials, borders and script hierarchy may make this a prestige volume for display, but they, and the vernacular text, also make it a volume for study. This was the most fundamental text for the clergy, and the heart of their active worship. | ||||

| The content of the psalter was based around the essential core of the Book of Psalms, songs of praise to God from the Old Testament and therefore part of the Jewish tradition from which Christianity derived. Also included were texts known as canticles, also Biblical songs of praise derived both from Old Testament books such as Isaiah, or from the gospels, such as the Canticle of Zachary in the book of Luke. The Psalms were usually given in Biblical order, but the order in which they were recited in church was based on the church calendar. A calendar was therefore an essential introduction to any psalter text. The psalter for liturgical use concluded with various creeds and sometimes the office for the dead. | ||||

| Occasionally the order of Psalms in the psalter was that of the liturgical round rather than the Biblical order, or else marginal notes were included which indicated where in the church calendar the Psalms were to be recited. Psalters organised in these ways are referred to as ferial psalters, in reference to the church feasts which they followed. These types of psalters grade into the organisation of the breviary. Later in the middle ages, psalters which were produced for lay individuals for private use often contained some extra texts, including prologues, hymns or prayers to saints. In this way they are evolving towards the book of hours. These categories are not immutable. | ||||

| The psalter might also include the Psalter of St Jerome, an abridgement of the entire Book of Psalms which could be recited in one day, for the benefit of those who, as a result of illness or for the benefit of their endangered immortal souls, had taken a vow to perform this act every day and then found it impossible. Jerome reported that he had been told by an angel that this was a perfectly acceptable solution. He was obviously compassionate as well as scholarly. There are, in fact, two different Latin translations of the Psalms which may be found in the Vulgate Bible, both produced by Jerome. The first, or Roman version, was a tidying up of various Old Latin versions of the Psalms while the second, or Gallican version, was a new translation from the Hebrew. | ||||

| There are various websites with interesting psalter material. Aberdeen University has produced The Burnet Psalter and The St Albans Psalter Project, both full digital editions with images, text and commentary. Glenn Gunhouse's Home Page contains a parallel Latin-English Psalter text. | ||||

| |

||||

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||