|

| Church

Liturgy |

|

There

is no record of any liturgical

books except the Bible

in the early Christian church until around the 4th century. By the end of

the middle ages there existed an array of books containing the texts, music

and instructions for the complete performance of all the various ceremonial

activities practised within the church. There were books containing all the

components of various services, and special books for the use of the bishop,

the priest, the deacon, the reader or the choir. |

| The precise content of the liturgy, including the mass and the divine office, was not absolutely fixed either in time or space. There were variants between different dioceses and orders. The Cluniacs, for example, were renowned for their lengthy and elaborate liturgy, while the mendicant preaching orders such as the Domincans and Franciscans, or the local parish priest, had other duties which prevented them filling their entire day with worship. Particular geographical areas included feasts to favoured local saints in their liturgical round. |

| Various

categories of works were introduced for specific purposes, and over centuries

were assembled into the larger compilations. One of the first works recorded

was the diptych;

lists of persons and churches for whom prayers were to be said, read by

the deacon down to the middle ages. They consisted of two tablets folded

like a book with the names of the living on one side and the names of

the dead on the other. |

| The

first books of the Western rite were the sacramentaries,

originating in the 7th or 8th century. This was the book of the mass,

but it did not contain the complete service, only the part of it spoken

or chanted by the priest celebrating the mass himself. It contained no

lessons or parts for the choir. It also contained services that were particular

to a bishop and could not be performed by an ordinary priest, such as

ordinations, consecration of a church or altar, exorcisms and certain

blessings.

|

|

| |

Pope

Gregory at mass depicted in a 15th century stained glass window in All

Saints, North Street, York. |

| Separate

books for the readers and for the choir were compiled for use in the mass.

The evangelary

or lectionary

contained the Bible texts to be read during the service. A benedictional

contained prayers for use in the service. Homilaries

contained the Homilies of the Fathers, while the martyrologies

contained the lives and deaths of the martyrs, to be read on their feast

days. |

|

|

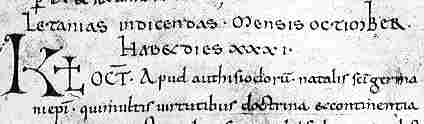

| Segment

from an 11th century martyrology of Odo, bishop of Vienne, who died in

the late 9th century (Avignon, Musée Calvet, MS 98). |

| The

parts of the mass sung by the choir were arranged in the gradual,

sometimes referred to as the Liber Antiphonarius Missae. There were also

separate collections of hymns arranged in hymnals.

A troper contained

the tropes, a short series of words added as embellishment to the text

of the mass or divine office by the choir. Tropes went out of fashion

around the 12th century, to be replaced by a different form known as sequences,

although the term troper was still used to describe the book in which

they were recorded. These manuscripts were usually very large so that

a whole choir could use them at once. |

|

| |

The

medieval choir stalls of Ripon Minster in Yorkshire. |

| Volumes

called ordinals

were produced from the 8th to the 15th century. These did not contain

texts or prayers, but instructions as to what to do at particular stages

of the ritual. |

| Changes

to the conduct of the mass caused changes to the text used by the celebrant.

At Low Mass the priest had to supplement personally what was chanted by

the deacon and sub-deacon and sung by the choir. In High Mass he also

began to sing quietly the parts sung by someone else. The sacramentary

was expanded by the addition of the lessons which were read and the chants

of the choir until it became the complete text of the mass, the missal.

This work was exclusively for the use of the priest, and were not usually

highly decorative illustrated works, although there are exceptions. The

conduct of the mass depended on its place in the church calendar,

and this is reflected in the structure of the work. |

|

| |

Segment

from a 12th century missal (British Library, add ms 16949, f,iv), by permission

of the British Library. |

| Lectionaries,

graduals and tropers were still produced for the use of the readers and

the choir. |

| The

services that were obliged to be performed by a bishop, which had been

in the sacramentary, were not included in the missal. These formed a separate

work called the pontifical. |

|

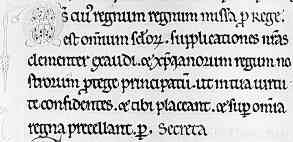

| Prayers

for the king in a 13th century pontifical of the Cathedral church of Sens

(Metz, Stadtbibliothek, Salis MS 23, f.131). |

continued

|

Categories

of Works Categories

of Works |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|