If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Great Big Bibles (3) | ||

| From the early days of the spread of Christianity throughout Europe, the pioneering writers of the church, known as the patristic authors, had produced works of commentary and explanation on the Bible, referred to in learned works as Biblical exegesis. These works aspired to connect the disparate elements that made up the Bible, from the mythologised narratives of ancient history in the Old Testament to the life and teaching of Christ and his apostles in the New Testament, as well as the predictions of prophets, songs of praise of the faithful and visions of seers, into a complete and holistic work of connected meaning. The bare bones of the miscellaneous texts that make up the work do not do that for themselves. | ||

|

||

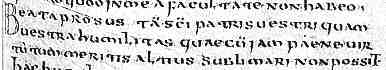

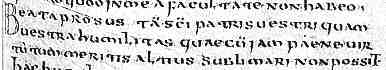

| A segment from the Homilies of St Caesarius, from a copy of around 700 AD (Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale, MS 9850-52, f.134). (From New Palaeographical Society 1904) | ||

| The above text is a grab from just one early exposition of the gospels. In the early days of monastic expansion, these texts were nearly as important as the Biblical texts themselves for providing a foundation for the religion. They were significant in early monastic libraries. | ||

| In the early 12th century compilations were made of various of these commentaries of the past for the purpose of inserting them into the pages containing the relevant Bible text. This compiled text was known as the gloss, or Glossa Ordinaria. In the later 12th century, the commentaries of Peter Lombard on the Psalms and the epistles of St Paul, known as the great gloss, or Magna Glossatura, were also included. These glossed books of the Bible were originally produced as single volumes, but evolved into large and elaborately constructed glossed Bibles. | ||

| The complex forms of page layout needed to place the appropriate commentary, in a small, simplified and compressed Gothic script, close to the appropriate section of Biblical text, in its larger and more formal Gothic textura script, meant that the process of producing these works required artfulness and planning. The gloss could run down the sides, between the lines, or form blocks around the main text. The actual page size of some of these works might not have been so large as those of some of the earlier large Bibles, but the whole work was becoming a massive enterprise. | ||

|

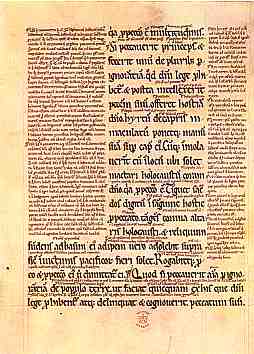

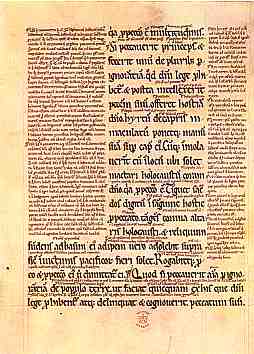

This example shows the text of the gloss, in a tiny red script, in two blocks on either side of the main text, as well as creeping in between the lines. This is more than a fair copy of the main text, and something other than a grand display volume. It is a whole compiled library for intensive study and contemplation. The medieval process of expansion and compilation has been applied, not to the core text, but to the vitally important adjunct reading material. | |

| The book of Leviticus and the gospel of St John, with commentary and glosses, written at St Mary's Abbey, Buildwas in 1176. In the British Library. | ||

|

||

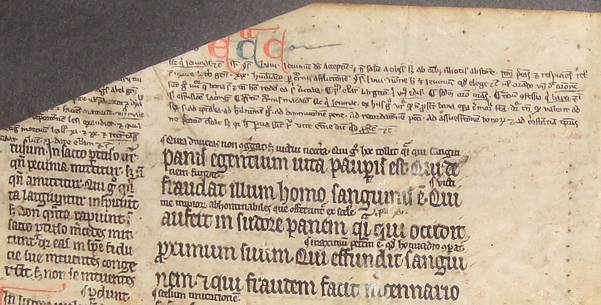

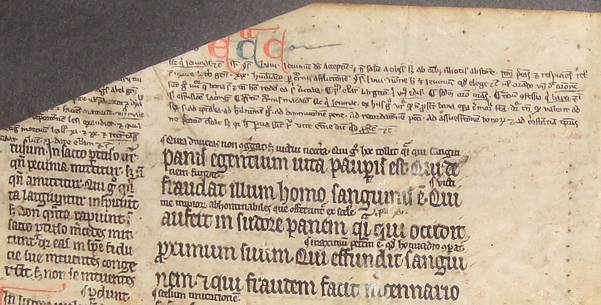

| Segment from a glossed Bible leaf, from a private collection. | ||

| The above image is part of a scruffy scrap of bookbinder's waste that was floating around cyberspace. (The fate of many old manuscripts was to be chopped up for binding materials in the days of printed books.)The formal gloss is written in a Gothic textura which closely resembles the rather florid script of the main text. It sits in blocks in the margins and forms interlinear text. As well, there is a less formal gloss in the upper margin written in a tiny, relatively informal, highly abbreviated, cursive hand; the sort that is absolutely rotten to try to read. The text is from Ecclesiasticus, also known as Sirach, a book of the Old Testament apocrypha. Despite being a wee little fragment, it gives you an idea of how complex the whole text was for reading. | ||

| In the 13th and 14th centuries the production of large, grand Bibles was decreased in favour of smaller and more portable works for teaching and preaching. The big prestige Bible made a comeback in the 15th century, accompanied in the church by large format liturgical books such as antiphoners. It seems that the written word was a major display item in church ceremonial at this time. When the first volumes were produced with that newfangled invention, movable type, the big display Bible was the first work produced. Perhaps Gutenberg thought that he could deflect assertions that his invention was the work of the devil by applying it immediately to the word of God. The bold Gothic textura script of the Bibles was converted in Black Letter Gothic typeface, which was used for printing German books until well into the 20th century. | ||

| Images of Gutenberg Bibles on the web can be found at Gutenberg Digital and The Gutenberg Bible at the Ramson Centre. | ||

|

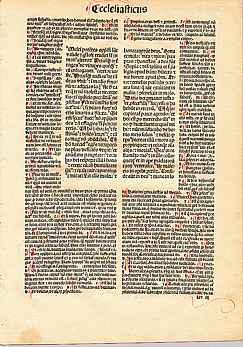

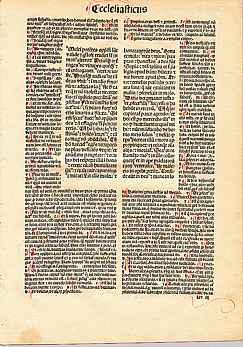

A page from a printed glossed Bible from the late 15th century in Germany, from a private collection. | |

| This example shows that the early printed works followed the same page layout conventions for glossed works as did manuscript Bibles. This must have been no mean feat to get it all correctly organised with hand set type. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||