If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Great Big Bibles (2) | ||||||

|

For the early period of production of Bibles, gospels and other liturgical books, we have an image of a single monastic scribe, or sometimes more than one, toiling away for months at the work of a single volume. This method of working is confirmed by colophons in the transcribed works, and by descriptions in chronicles and the like of how the scribes were working. Books were borrowed for copying within the libraries of the monasteries. Sometimes the scribe was also the artist who produced the illustrations. It appears to have been a work of solitary dedication. | |||||

| The work of producing many copies of these massive complete Bibles, all from authentically correct exemplars, required a different method of work. It seems that scribes may have been employed to visit libraries where approved exemplars resided and copy them there for monastic clients. At that time those who were litteratus, or competent in written Latin, were also most likely to be clericus, or ordained members of the church. However, there were by this time increasing numbers of secular clergy, canons of cathedrals or collegiate churches, or members of the Augustinian orders, who were not bound to live in enclosed convents and who may have been more free to travel to do this work. Like so much about the history of the development of writing as a profession, it is not known exactly how this was organised. | ||||||

| Some monastic orders developed their own particular styles. The rantings of St Bernard of Clairvaux against the excessive use of colour and gilt to the detriment of the sacred words, resulted in Cistercian Bibles where the decorative letters are all presented in subtle shades of monochrome, often blue. Some of these are quite exquisite, but by the later part of the 12th century, they had reverted to the same decadent track as the other orders woth lavish multicoloured illuminations adorned with gold leaf. |

|

|||||

| Statue of St Bernard in the church of his birthplace at Fontaine-les-Dijon. | ||||||

| The Municipal Library of Troyes had a beautiful online exhibition La Bible de Saint Bernard, however it seems to be no longer available online. You can see some illustrations of the manuscript treasures of Troyes on the blog BibliOdyssey: The Treasures of Troyes. The last illustration on the page is a blue monochrome initial from a 12th century Bible. The Library at Troyes holds a huge collection of manuscripts from the monastery of Clairvaux. I have a CD-ROM of a wonderful exhibition of Cistercian manuscripts held in Dijon, Treasures of the Lowly, but as far as I can ascertain it is no longer available. If you see one on eBay (the CD-ROM that is), buy it. | ||||||

| Medieval texts in general had a tendency to grow and accumulate as compilations. The works of previous authorities were mined, extracted and reassembled to form the ever increasing body of knowledge of the written word. The Bible text was something of an exception, but not entirely so. The tidying up of the Biblical text which periodically occurred, as in the Carolingian era, was to restore the text to an accurate rendition of St Jerome's Vulgate, removing accumulated scribal errors and also remnants from earlier Old Latin translations. The Bible text was about the only one in Christendom that was not allowed to develop and grow in complexity. | ||||||

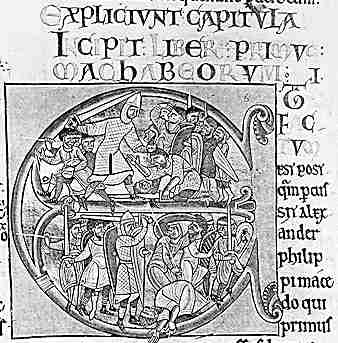

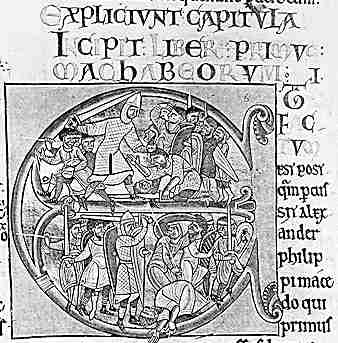

| Beginning of the book of Maccabees from a late 12th century Bible in four volumes (Durham Cathedral Library MA A. II. 1). (From The New Palaeographical Society 1912) |

|

|||||

| Jerome, in a spirit of textual cleansing, had excised from his version of the Bible certain books, which did not have an original Hebrew text, on the basis that they were not authentic. Later authorities, feeling a little uneasy at the possibility of having rejected what may, in fact, have been holy word, sneaked them back in again. The above example shows the beginning of the book of Maccabees, one of those texts now described as Apocryphal. | ||||||

| Jerome himself wrote introductions and commentaries on the complete work, and on certain books. These, along with other summary and organisational material such as the canon tables, were included along with the core text from the earliest days. In terms of the use of prestige decorative elements such as elaborate headings scripts or historiated initials, these could be given the same weight as the core text. | ||||||

|

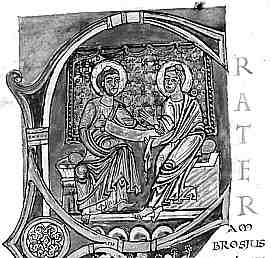

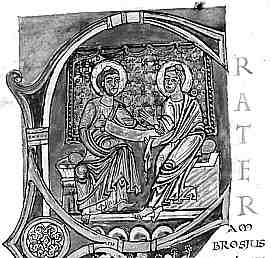

Detail of a historiated initial from the beginning of the general prologue to the text, in a late 11th century Bible from Stavelot, Belgium (British Library add ms 28106, f.2v), by permission of the British Library. | |||||

|

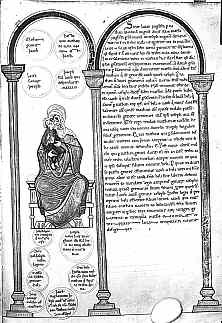

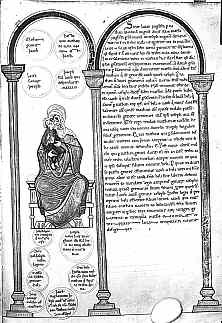

This page of commentary on the gospel has a splendidly Romanesque image of the Virgin and Child, and text arranged in an unusual manner in little interconnected circles and under architectural canopies. The script, an exceptionally neat but quite heavily abbreviated protogothic, has certain idiosyncratic calligraphic flourishes such as are found in highly significant church documents of the period, including peculiarly extended ligatures and horizontally elongated majuscule letters in odd places. | |||||

| Page from a mid 12th century Bible from the Premonstratensian monastery of St Maria de Parc, Belgium (British Library add ms 14788), by permission of the British Library. | ||||||

|

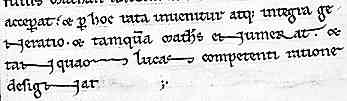

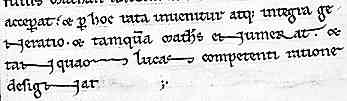

Detail of script from the bottom of the second column. | |||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||||