If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Little Tiny Bibles | |||

| The 13th century was a time at which the church took another evolutionary step, this time in relation to the perceived threat of heresy, particularly from the group mainly based in the south of France and known as Albigensians or Cathars. The battle was fought with swords and words, and while the armies with God, or at least the God of the medieval church, on their side did a bit of biffing and burning in the name of correct thinking, new varieties of monastic orders were created in order to take the authorised word of God to the people. | |||

|

The order of Dominicans was founded specifically to counter the Cathar heresy. While that famous proto-hippie, St Francis of Assisi, thought he was renouncing all worldliness to live with his likeminded brothers in absolute poverty and simplicity like Christ's apostles, the authorities of the church were also grooming his Franciscan order to preach religious orthodoxy in the towns and countryside. Francis, a wayward charismatic leader performing medieval mediagenic acts like developing the stigmata of Christ on his hands and feet, was a little harder to keep on the orthodox track himself than his Dominican counterpart, St Dominic. The new mendicant orders of friars such as the Dominicans and Franciscans lived in communities, but were not enclosed like the Benedictines. They took up their posts in major towns where they got about and preached to the people. Their major function was not the daily round of performance of the liturgy, but teaching in public places. | ||

| A Franciscan | |||

| It is therefore no coincidence that a new style of Bible began to be produced at around this time. The very tiny modified Gothic script which had been used to produce the glosses in large Bibles was employed for the text of the whole work. The parchment used for the pages was worked extremely thin and white. The result was complete Bibles in single volumes that were quite portable - just the thing for a Dominican to pop into his saddlebag to head for the hotbeds of Languedoc. The main centre of production, but not the only one, was Paris. | |||

| More details about the production of small 13th century Bibles can be found in De Hamel 2001. | |||

|

These works introduced new standards in relation to the production of the Bible. Whereas earlier versions of the Bible all contained the same books, there was some variation in the order in which they were presented. These works established the order of the books pretty much as we know it today. The pages were laid out in neat double columns, and although they did contain some of the locating and reading aids such as historiated initials and borders, the page design was much more sparse than in the earlier, more spacious volumes. They introduced a locating guide that is still familiar to us today; the division of the books of the Bible into numbered chapters and verses. Similar aids had been employed before, but there was not, until then, a single standardised system. These numbers, and running headers with the names of the books of the Bible at the tops of the pages, were added in red and blue ink. The text was not only under control, it was archived and catalogued. | ||

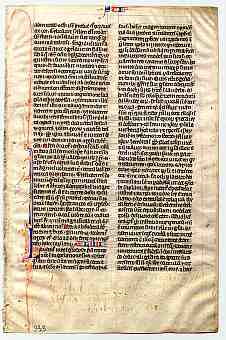

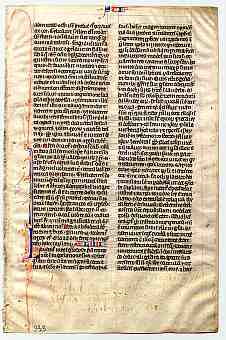

| A leaf from a 13th century portable Bible, showing a section of the book of Ecclesiasticus, or the Wisdom of Jesus Son of Sirach, from a private collection. Below, a detail, somewhat enlarged, of the script and decoration. | |||

|

This detail from the lower left corner of the page shows some of the very characteristic fine red and blue penwork decoration on important initials, a chapter number, and little bits of red highlighting at the beginning of every sentence. These are all aids to locating and reading the text, not frivolous decoration, but one gets a strong impression that a travelling Dominican preacher needed very good eyesight. | ||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||