If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Early Bibles and Gospels | |||

| The missionising monks who set up their literate enclaves across Europe from Rome to Ireland transported and copied books for their purposes. Manuscript books were rare, expensive and labour intensive commodities at this time. Their most pressing necessity was for the fundamental works for the learning and practice of the Christian religion; the books of the Bible and the psalter which provided the essential texts for the practice of the liturgy. |

|

||

| More details on early volumes of the Bible can be found in de Hamel 2001. | Some ruins from the monastery of Kells, a distant outpost of early Christianity. According to legend it is the house of St Colum Cille. | ||

| The production of a whole Bible was a massive undertaking at this time, and parts of the Bible were produced in segments, notably the most fundamental text of the lot, the gospels. Very few of these early works survive. Most of them were probably used to death or replaced by more trendy, modern, fancy glossed Bibles in later centuries. It is perhaps not surprising that of those that do survive, a disproportionate number are very elaborate, prestige works that were treasured for centuries and probably only brought out for use on very special occasions. Fragments of the every day service books have sometimes been found in odd places; as pastedowns in later books, as wrappers or just fluttering about as lost leaves. | |||

| We tend to think of the Bible as a standard text, but the Bible as we know it has evolved much over the centuries. In the early days there were various Latin versions of the text floating around, in many cases inaccurately transcribed. The versions that were extant before St Jerome's Vulgate translation became the standard Latin text are generally referred to as the Old Latin versions. | |||

|

|||

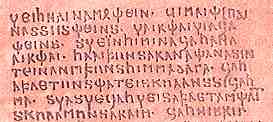

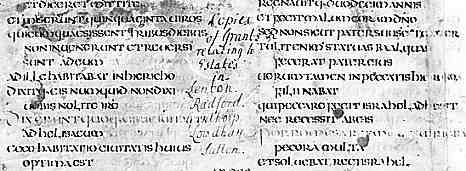

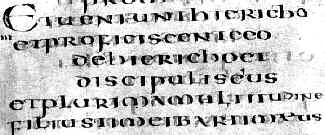

| This is a small segment of a leaf from the Codex Palatinus (British Library, add. ms. 40107, f.1), an Old Latin version of the gospels from the 4th or 5th century. By permission of the British Library. | |||

| The above text is written in two columns, in uncial script which runs continuously without word breaks. Enlarged capital letters provide the only clue to place marking. It was a prestige volume written in silver on purple vellum. (Don't you wish we had a colour picture!) The priests at this time must have had prodigious memories, knowing their readings by heart, and the book probably served as a prompt. It was a ritual object of significance as much as a text. | |||

|

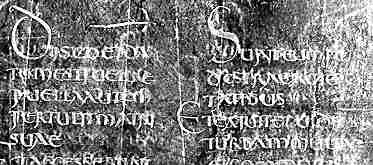

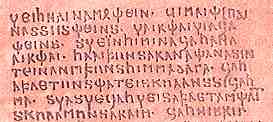

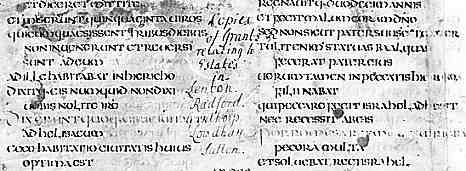

Segment from the Codex Argenteus in Uppsala, a 4th century Gothic language Bible text. Yes, this is a poor image, but that's what happens when you are confined to old books, and metallic silver doesn't scan well. | ||

| While Latin was the official language of the western church, there were early attempts at vernacular texts. The Gothic language Biblical text illustrated above was a prestige volume written in silver ink on purple vellum. It is a rare survivor, as Gothic texts were destroyed, and sometimes scraped down and written over, because of their association with the Arian heresy. The above is written in a majuscule script, with a runic character representing th. The text is part of the Lord's prayer. | |||

| A better image of a page from this manuscript can be found here on the Codex Argenteus website produced by Uppsala University Libraty. | |||

| The elegant but laborious uncial script continued to be used for Bibles, gospels and psalters produced from and under the influence of Rome, and in southern centres of England such as Canterbury. St Jerome's Vulgate became the standard text, although even by the time of Charlemagne they were still trying to weed out the Old Latin versions from the monasteries. (I'm sorry, I don't believe Charlemagne actually did this himself. He was much too busy thudding up Saracens and conquering people. But he got his name associated with learned men pursuing this cause.) The adoption of the standard Vulgate was not as rapid or as absolute as it is sometimes represented. Jerome translated the Old Testament afresh from the Hebrew and the New Testament from the Greek. He made three attempts at translating the Psalms, and excised books from the Old Testament that had no Hebrew versions. These were later reinstated from the Old Latin versions, and are known as the Old Testament Apocrypha. | |||

|

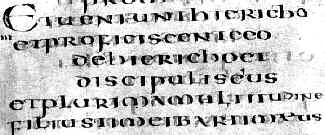

6th century Italian gospel in uncial script (British Library, Harley 1775, f.195). By permission of the British Library. | ||

| A script example and paleography exercise for this manuscript can be found on this website here. | |||

| Uncial script was not only laborious to write, it was very space consuming. It took a lot of sheep to make a volume of the gospels, and parchment was expensive. | |||

|

|||

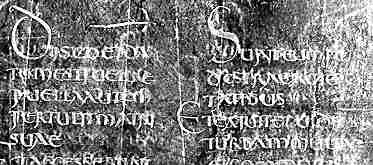

| A segment from the Middleton leaves of the Ceolfrith Bible (British Library, add. ms. 45025), from the late 7th or early 8th century. By permission of the British Library. | |||

| The above example shows how profligate uncial script is on the page, especially when scribes start to introduce word and line spacing to add comprehensibility to the written text. The much later writing in the middle tells something of the history of this piece of parchment, which was used as a wrapper for estate documents belonging to Lord Middleton. Sacrilege perhaps, but at least this bit of the work survives for posterity. | |||

| Scribes in Ireland and the north of England in Northumberland developed a more elegant solution, and produced some of the most famous surviving works in this genre. | |||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||