|

|

Vernacular

Languages (2) |

|

Travelling

entertainers like the troubadours

of southern France and the Minnesinger

of Germany carried vernacular

poetry and song around the courts of Europe, but this was almost entirely

an oral tradition. A written form which appeared in the French vernacular

was the romance,

undoubtedly derived from this earlier oral tradition. |

|

|

The

oldest manuscript of the famous Chanson de Roland, describing

some adventures of Charlemagne, dates from the 12th century. Legends of

King Arthur of England appear in French romances. The mammoth French romance

Le Roman de la Rose was composed in the 13th

century and over 200 manuscript copies of this work survive. Latin texts

were also translated into French. The motivation for the production of

these often lavishly illustrated works was their flaunting in the libraries

of wealthy French aristocrats. |

|

|

|

The

earliest works in the German language were in fact recorded by Anglo-Saxon

scribes in the

missionising monasteries of the 8th century. However, an expansion of

German vernacular literature occurred much later when the French epic

and romance tales were adapted into German. Around 1200, original poems

and tales of this nature were composed in the German language, including

the famous Nibelungenlied. |

|

Vernacular

songs in the Galician dialect were written by King Alfonso X of Spain

in the mid 13th century. Lavish manuscript copies of some of these survive. |

|

In

the 14th century the use of vernacular languages in literary forms became

well established. In England, the works of Chaucer were significant in

establishing Middle

English as a language of literature. Many works of prose and poetry

appeared in the vernacular. While spelling still had no standardisation,

the development of a literary tradition was a major step in developing

a standardised form of the language, comprehensible to people from various

dialect areas. |

|

|

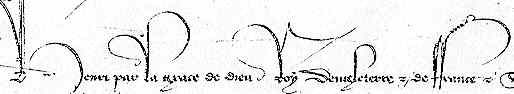

The

earliest known portrait of Chaucer, from a manuscript of Hoccleve's Regiment

of Princes (British Library, Harley 4866, f.88). By permission

of the British Library. |

| In Italy,

Dante’s insistence that his monumental experiential religious journey from

the depths of hell to the heights of heaven should be produced in the Italian

vernacular similarly established a literary form of the language. Certain

aspects of his literary style still permeate the more elaborate forms of

the language. |

|

|

Ireland

was recovering from Anglo-Norman invasion and settlement at this time.

A consequential dearth of Irish literature during the 13th century was

followed by a conscious revival of Gaelic literature and of the older

form of Irish scripts in the 14th century. |

|

The

formal literature of the church, including the Bible

and works of liturgy,

remained in Latin during the course of the middle ages. English language

Bibles, known as Wycliffite Bibles after John Wycliffe who inspired the

work of translating them, were denounced and eventually banned as a result

of their association with violent heretical movements. However, the appearance

of vernacular works designed for the religious instruction of the laity,

or for their moral improvement, may testify to an increase in vernacular

literacy in the later part of the middle ages. |

|

The

increasing use of the vernacular form from the 14th century onwards shows

in manuscript material of many types, including legal documents. In England,

English had overtaken French as the language of all social classes and

it was increasingly used for legal transactions, although royal documents

of the time of Henry V can be found in French. He had become king of France,

of course, and language and politics are ever intertwined. |

|

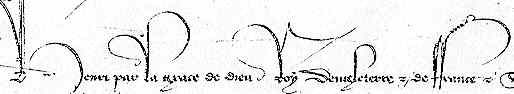

| Beginning

of a warrant of Henry V, from a document in the National Archives, London

(C81/662/483), by permission of the National Archives. |

|

Henry

V notwithstanding, English became the language of prose and poetry, history

and chronicles, medical and practical texts, wills, charters and private

letters. By the time of Shakespeare, he could have a character in Richard

II, condemned to exile, moaning piteously about how he would have

to spend his life deaf and mute in the absence of his native tongue; a

condition that might have applied to the time of Shakespeare but not to

that of Richard II, when a member of the aristocracy might well have been

just as at home with French. |

|

The

development of the languages of English, French and German occurred after

the fall of the Roman Empire, and the politics of war and conquest had

much to do with their progress. The languages change greatly during the

course of the middle ages, and there were many dialect differences within

them. Languages such as Breton, Basque, Cornish, Welsh or the Gaelic of

Scotland survived as pockets from earlier traditions, but they are represented

in only minority form in the literate tradition. Irish, however, developed

its own vernacular literature. Texts in even the more familiar languages

of French, German or English may look very unfamiliar, and it may be necessary

to utilise an array of dictionaries and linguistic aids in order to tackle

them. |

previous

page previous

page |

Reading Manuscripts

Reading Manuscripts |

Why Read It? Why Read It? |

|

|

|

|

|

|