If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Literate English (2) | |||

|

The invaders consisted, according to Bede, of Angles, Saxons and Jutes. This is repeated like a mantra in many schoolbooks, and no doubt there were distinctions between the groups of invaders according to their areas of origin; northern Germany, the German-Danish border area and the Jutland peninsula of Denmark. It is quite unclear exactly what degree of ethnic or linguistic integrity these individual groups had, but they all spoke West Germanic variants of the Germanic language. | ||

| According to old schoolbook imagery, they were all very fierce and hairy. | |||

| Now we get to a bit of a sticking point in language studies, as a whole school of linguistic studies is based around the concept that languages constantly differentiate, and for every language family there is a common parent language spoken by the ancestors of the speakers of the various variants. The model is like a slowly growing Tower of Babel. There is a logic problem here for me, as the only evidence for non-literate language prototypes is the surviving vocabulary, while the lost words cannot be recovered anyhow. Past differentiations in language are obscured, and only the common threads remain. For dialects whose variants have been swallowed into related languages, the differences are lost forever. Whether or not all the Germanic languages differentiated from a proto-Germanic prototype located in a particular time and space, we do know that the languages of these invaders formed the structural basis for English, which is, at its core, a Germanic language which has undergone many transformations. | |||

| Another statement from Bede is constantly reiterated, and let us remember that he was a monk living in an isolated location writing a very excellent history of the Christian church, in the 8th century, long after the events, from selected literate sources in Latin. He stated that the British people were driven from England into the fringe areas of Wales, Scotland, Ireland and Cornwall. That simply means that there were no longer any speakers of the old Celtic languages in England, not necessarily that there had been wholesale slaughter or massive migration. There had been genocide in the form of cultural extinction, however, as language is perhaps the primary marker of cultural distinction. | |||

|

|||

| The remains of the monastery at Jarrow, home of Bede and more closely connected to Rome than to the doings of the peasants, or kings, in the English countryside. | |||

| In the early days of the Anglo-Saxon invasions, we simply do not know what mosaics of language patterning formed, altered and were obliterated by later patterns. There is no written evidence for this stage of language development. The Anglo-Saxon invaders settled into rural areas and small settlements generally outside the old Roman towns, which quietly fell to ruin. If they absorbed many members of the existing rural population, by the time that literate English appeared, Celtic influence on the language was negligible, and any Romanising influence on the Celtic language had been obliterated. And yes, even if you go for the old fashioned "rape and pillage" model of the Anglo-Saxon invasions rather than the New Age peaceable farmers in search of pastures green, have a think about what that implies for the genetics of the population. | |||

| By the time that the Roman armies departed from Britain, Christianity was the official religion of the Roman Empire, although it is not apparent how widely it was disseminated among the indigenous people of Britain. Any routes of continuity with Celtic Christianity as derived from Ireland are not elucidated. A miracle conversion story, as for St Patrick, is more mythworthy than a faint and flickering link to a half forgotten past, reinforced by later reincorporation into the missionising church. The Anglo-Saxon invaders were both pagan and illiterate. The 7th century conversion of the English provided the means by which the Old English language first became written down. | |||

|

|

||

| At left, a schoolbook image of Anglo-Saxon raiders pillaging a church in a Roman fort abandoned by the army. At right a depiction of the myth of Pope Gregory encountering some Anglian slaves in the Roman marketplace and making the utterance "Non Angli sed angelii" ("Not Angles, but angels") and immediately deciding to convert England. You might wonder how such evil looking characters could have such exquisite kids, and have you ever thought how these crazy images affect your view of history? Sorry, personal obsession. | |||

|

|||

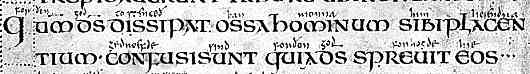

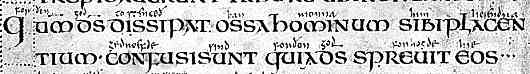

| Two lines from the Vespasian Psalter, of the early 8th century, with mid 9th century Old English gloss (British Library, Cotton Vespasian A1, f.53), by permission of the British Library. | |||

| The above example of an Old English gloss represents an early written Anglo-Saxon text. It is not a grammatically correct rendition, as the Old English words are simply written above their Latin equivalents, no doubt to assist English clerics whose Latin was less than perfect in the recitation and understanding of their liturgy. Old English works which appeared from the 9th century onwards included Bible texts, poems with religious themes or imagery, translations of Latin works including a Latin grammar, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a historic compilation maintained in various copies in major churches and monasteries. In other words, these works may represent the vernacular language of the people, but they are still the voice of the church. | |||

|

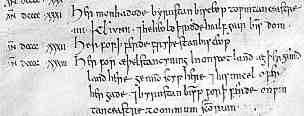

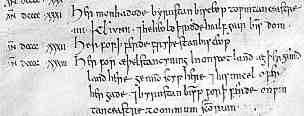

A segment from the Parker manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 173). (From New Palaeographical Society 1908) | ||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||