|

|

Parchment

(3) |

|

While

parchment was

expensive, it is very durable under the right circumstances. When all

the books of today printed on non-archival acidic paper have crumbled

away, those ancient codices

and charters have

a good chance of being not too much the worse for wear. If you go into

a library or archive today you may find the artifacts stored under optimal

temperature, humidity and lighting and you will probably be required to

wear white cotton gloves in order to look at them. This is to ensure the

best possible preservation conditions, but they may have survived many

centuries in more rugged situations. Much used books like works of liturgy

or books of hours

have been thumbed by many greasy fingers, but those who have worked with

collections of documents rather than exquisite illuminated

manuscripts

claim that the white gloves are a great comfort when you see what ancient

gunk can come off the documents. |

|

Chained library |

|

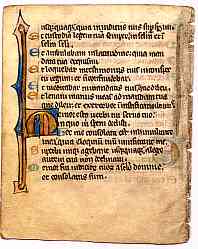

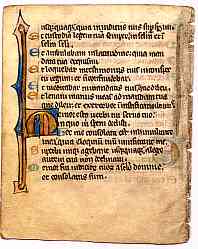

Page from a small portable psalter or breviary of the 13th century, from a private collection. |

| This page is a favourite of mine because it is absolutely filthy. This is no carefully curated museum object. Dating from the times of the Dominicans battling the Cathar heresy, it seems to have the brown dust of Languedoc and the greasy sweat of its owner ground into it. The gold leaf on the lettering is wearing off. One can imagine it travelling for miles in a saddlebag and being hauled out in dusty town squares for a bit of berating of the peasantry. OK, so I'm getting a bit carried away here, but the vellum is still in completely sound condition around 800 years on. |

|

|

|

|

|

The

greatest enemy of parchment is moisture or high humidity, which can cause

the flat sheets to buckle, painted decoration to peel, mould to develop

and can also cause the ink, which usually had an acid formulation, to

eat into the parchment itself. However this last characteristic can also

be utilised to render visible writing which has faded into illegibility. |

|

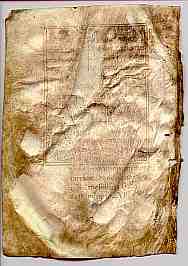

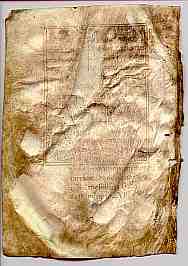

Buckled page from a small Italian book of hours of the 15th century, from a private collection. |

| This page from a small book of hours has been less fortunate than the example above, having apparently been affected by moisture, causing the parchment sheet to buckle and the ink to fade. It has a sketch for an unfinished miniature of Pentecost, illustrating the Hours of the Holy Spirit. It is a sad little relic. |

|

At

one time writing which had faded away could be rendered more visible by

treating the page with gall, which made the writing clearer but covered

the page in a rather nasty splodgy mess. This was not done on posh illuminated

manuscripts but on more humble documents whose value was seen to be to

the historian rather than the aesthete. Later it was found that ultra

violet light rendered ink more visible, but historians and archivists

seem to have been a little cavalier on the effect it had on human eyes.

When I was a young thing studying chemistry we could only use UV lamps

using special glasses, eye shields and cabinets while my medievalist future

husband was frying his retinas under direct UV lamps in archives. Today

there are various enhancement techniques which use digital photographic

methods to make even very badly damaged text more visible without harming

either the manuscript or the reader. |

|

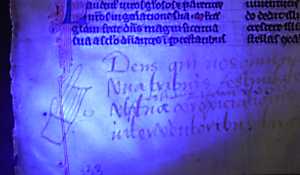

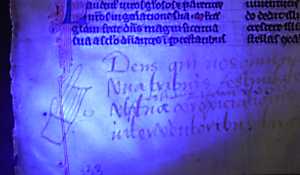

Faded inscription added to a 13th century Bible leaf in a much later hand, viewed under ultra-violet light, from a private collection. |

| The

point is that the parchment membrane may be more robust than the inks

and pigments used to adorn it, but there are ways to reveal the traces.

The most devastating cause of damage, apart from active human destruction,

has probably been fire. During the medieval period itself there were times

when whole monastic libraries went up in smoke, fire being a general hazard

under the conditions of those times. In later times one of the founding

collections of the British Library, the Cotton collection, was reduced

and some of the surviving manuscripts damaged by fire while it was still

in a private library. In an ironic twist, some of the damaged books which

had been sent for rebinding were later destroyed by a fire in the bookbindery.

To a bibliophile, this tale requires a bigger box of tissues than Black

Beauty. |

|

The

replacement of parchment by paper in the later medieval period was encouraged

by cost, convenience and the proliferation of the written word. Parchment

became one of the significata of status in a book or a document. With

legal documents, which continued to be handwritten long after books were

being produced on the printing press, the use of parchment conferred a

significance to the document as an object. Calligraphic scrolls or certificates on parchment have been produced for highly important

persons or occasions into our time. There is just a hint here of a very

ancient tradition in which an early medieval charter was not so much a

legal document full of written text, but a prestige object which signified

that an important legal transaction had been carried out in the presence

of witnesses, but that is another part of the story. |

|

|

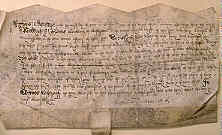

An

indenture from the time of Henry VIII is written on parchment and follows

the general medieval format. From a private collection. |

previous

page previous

page |

Tools

and Materials Tools

and Materials |

|