If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Parchment (2) | |||||

| There is some confusion in relation to the use of the terms parchment and vellum. Some authorities claim that parchment is derived from the skin of sheep or goats while vellum comes from calves. The term vellum is also used specifically for skin which has been abraded with pumice, a procedure more likely to have been used on the thicker calf skin to stretch and soften it further. However, the terms are also used interchangeably and some libraries use the term parchment in their catalogues for all their skin based writing membranes; others use vellum. In the light of a general lack of agreement, you may please yourself. | |||||

| Turning the prepared skins into pages would be much easier and more efficient if sheep and cows were rectangular, but they are not. An appropriate sized rectangle had to be cut out, then progressively folded and cut to form the quires or gatherings for a codex. Rectangles folded up at the bottom were used for single sheet documents with seals attached. Rectangles were sewn together in linear fashion to make rolls. Presumably some of the leftover bits could be used as strips for attaching seals, tying up documents or a myriad of handy little purposes. | |||||

| Because of the numbers of animals required to produce the membranes, parchment was expensive. I'm sure that someone with a mathematical bent has worked out how many sheep it took to make a large 12th century Bible, but it would have been a flock. There is evidence for this, especially in the early medieval period, in relation to the re-use of parchment. Some early monastic libraries, most particularly the monasteries of Bobbio and Luxueil, have numerous palimpsests in their collection. These are manuscripts which have been scraped down and rewritten, but the underlying writing can be detected beneath. As some of these obliterated texts were heretical writings which had been banned by the church, this paleographical archaeology can be used to study the development of authority in the early church. They also contain texts in Greek, Hebrew and the language of the Goths. | |||||

|

|||||

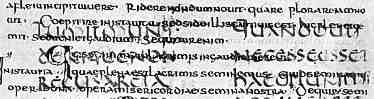

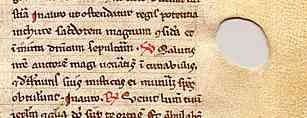

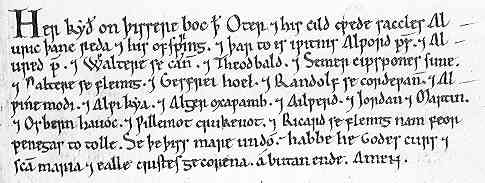

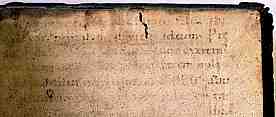

| A sample from a palimpsest (Rome, Biblioteca Vaticana, Vat. Lat. 5757, p.86). (From Steffens 1929) | |||||

| In the example above, the large script is a 4th century version of Cicero's De Re Republica, while the overlying smaller script is a 7th or 8th century version of a commentary of St Augustine on the Psalms. It formerly belonged to Bobbio. | |||||

| The expensive nature of parchment may also partly account for the use of blank pages or spaces in books for what seem to be unrelated purposes, such as the recording of title deeds or legal documents in the blank leaves of early gospel books. The juxtaposition of legal and sacred material may also have been used to add solemnity to the former, of course. | |||||

|

|||||

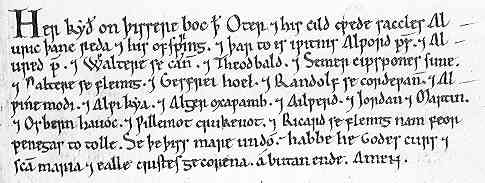

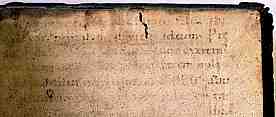

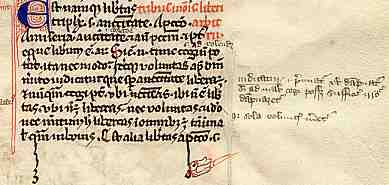

| A sample from a set of manumissions of serfs, formerly in a manuscript of Gospels belonging to Exeter Cathedral, now bound with the book of poetry known as The Exeter Book (Exeter Chapter Library, No. 3501). (From The New Palaeographical Society 1903) | |||||

| In the example above, the reference to kissing the book and the final Amen indicate that the presence of a legal document in a sacred book is not entirely related to the conservation of parchment. Nevertheless, the odd additions to blank leaves in books could become a study in themselves. | |||||

| As the culture of writing proliferated, the development of more compact scripts resulted in the more economical use of parchment. The transition from the large and rounded insular half uncial to compact pointed insular minuscule, and the transition from rounded Caroline minuscule to laterally compressed Gothic can be seen as two solutions, from different eras, to the same basic problem. The use of extensive abbreviation in verbose works squeezed more words to a page.Tiny glossing scripts which allowed large amounts of commentary to be added into the margins of pages of text saved sheep and calves at the expense of the eyesight of the readers. | |||||

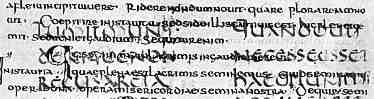

|

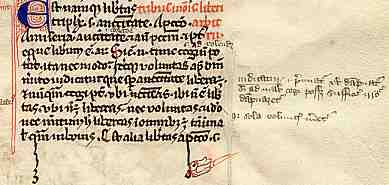

Segment of a page of the Sentences of Petrus Lombardus from the 14th century, in highly abbreviated Gothic script with minute marginal glosses, from a private collection. | ||||

| Sometimes damaged skins had to be used, and the writing may meander around a flaw or hole, which may even be embellished in some way with a bit of penwork decoration. | |||||

|

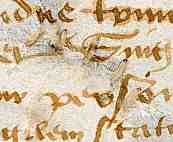

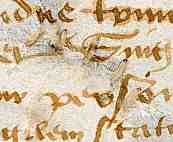

In this example a hole in the parchment has been stitched. As the ink goes over the stitching, this has occurred before the sheet was written on. | ||||

| Detail from a document of 1474, formerly in the private collection of Rob Schäfer. (Photograph © Rob Schäfer) | |||||

|

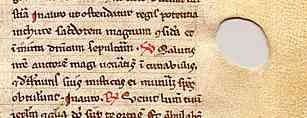

Segment of a page from a 14th century French breviary, from a private collection. | ||||

| In the example above, a leaf with a large round hole has been used. In this case, the hole fits into the page margin, but sometimes they appear in the middle of the text and just have to be dealt with. | |||||

| Parchment was always valuable and it is found re-used and conserved in various ways; in bookbindings and pastedowns, as wrappers for documents or sliced up to provide the attachment for seals. I guess there is always the chance of finding a lost text among such oddments. | |||||

|

A sheet of parchment with 12th century writing has been used as a pastedown in a 15th century volume of the works of Cicero, by permission of the University of Tasmania Library. | ||||

|

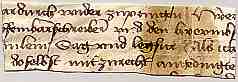

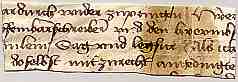

Writing on a seal tag from an indenture of 1426. The tag has been made from an earlier document. Formerly in a private collection. | ||||

|

A tiny fragment of a late medieval German language notarial document, found in the bindings of an early printed book, in a private collection. | ||||

| In the later middle ages when book production was a commercial enterprise, so was the production of parchment. The parchmenters were a trade with their own guild, one assumes working together with the butchers and tanners. Like other trades, their operation could be localised in the town and street names like Parmentergate as found in Lincoln for example, indicated where they plied their trade. | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||||