|

|

Law

and Administration |

|

In

his wonderful book From Memory to Written Record M.T. Clanchy makes much of a tale, often illustrated in old school books,

concerning Earl Warenne and the commissioners of Edward I. The legend

goes that when asked by what warrant he held his lands, the Earl pulled

out a rusty sword, brandished it at the judges and claimed that the sword

used by his ancestor at the side of William the Conqueror was his charter.

Clanchy gives many reasons why this story could not be strictly true,

including that even in ye olde medieval days earls did not go about flourishing

naked blades at senior legal personnel representing the king. However,

he feels that the story has a sort of symbolic truth in that the 13th

century had been a crucial time of change in the methods of the law and

administration. |

|

A

traditional schoolbook representation of Earl Warenne and his sword. Note

that he is even pointing the blade at the commissioners. I think you could get hanged for that. |

|

|

Clanchy's

study limits itself to England in the period 1066 to 1307, but it illustrates

many generalities about the transition from a mode of conduct based around

witnessed oral testimony to one based on a proliferation of written words.

Despite the book's dense content, it is a great read. If you can find

one, have a go at it. |

|

Arguments

about literacy can sometimes become very entangled in definitions of what

literacy is, but it is important to try to see through the heavily constructed

concept of literacy and the literate mode of living with which we have

been indoctrinated since birth. Grab any oldfashioned history book and

find where lack of written record is equated with complete illiteracy,

ignorance, chaotic government, bad architecture, social inequity, long

hair and poor personal hygeine. |

|

King

Alfred the Great, from the late 9th century, has been presented to history

as a man who prized literacy and learning, who had great books translated

from Latin into Old

English. Some even say he did it himself, but the man at the top often

gets the credit for the efforts of his workers. The famed Alfred Jewel

is supposed to be a very posh bookmark, presented to some careless person

to encourage the valuation of the written word by association with high

class accessories. It has an inscription, itself a valuation of the word,

and we presume it was that Alfred who was mentioned in it. |

|

The Alfred Jewel |

| The

Alfred Jewel is a gold, enamel and rock crystal assemblage with a socket

at the end thought to have once held a long pointer. Like a number of

things found in muddy fields in days of yore, it now resides in the Ashmolean

Museum, Oxford. The inscription reads ÆLFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN or

Alfred commanded me to be made. |

|

Alfred

did not, however, have a complex royal chancery

full of scribes organised into multiple secretariats. There are no archives

from his era, no books of laws, no records of the state of his treasury.

In fact, the number of legal or administrative documents dating from before

the Norman Conquest is extremely limited. |

|

Charters

or writs were produced

by Anglo-Saxon kings, so they knew about them and they used them. Of the

surviving 2000 or so, only a fraction exist as original authentic documents.

The rest survive as copies or later forgeries. It is impossible to answer

the question of how many have been lost to history, as in the absence

of an archiving system, lost is lost. |

|

|

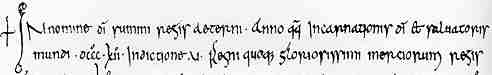

A

segment from a charter of Coenuulf, King of Mercia, of 812. |

|

What

is known is that it was long after the Norman Conquest before legal and

administrative affairs were conducted in a truly literate mode. The charter

or writ was really a ceremonial object which served to symbolise a transaction

carried out in oral mode. This does not mean that people were necessarily

completely illiterate. It means that literacy was not conceptualised as

part of this aspect of living, which had a long oral tradition. |

|

Some

early charters were not dated. None were signed. They comprised a form

of public statement which was authenticated by the names of the witnesses

present. These witnesses did not sign either. Their names were entered

on the document by the scribe,

in pre-Conquest and early post-Conquest documents beside a sign of the

cross. This symbolised the solemnity of the witnessing process whereby

the witnesses swore an oath before Christ as to the truth of what they

were witnessing. Later authentication of the transaction required, not

the document itself, but the oral testimony of the witnesses. It was essentially

an oral process, the piece of parchment

not being a legal document in the modern sense of requiring all legalistic

conditions to be entered in writing, but rather being a symbolic object

whose existence testified that a legal transaction had been carried out. |

|

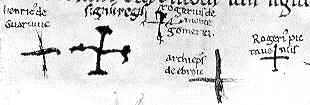

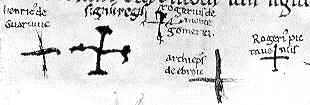

Crosses

of the king (second left) and some of the witnesses to a late 11th century

charter in Eton College Library. |

|

This

is how the story of Earl Warenne's sword has an aspect of authenticity,

even if it is not exactly true. A sword, a knife or another object could

serve as the token of faith in an oral transaction as well as a piece

of parchment scribbled on by a scribe. In the period of transition, there

are written records which refer to the process of oral testimony. |

|

|

|

A

grant by knife  |

| In

the days before the existence of a royal chancery, when the scribe was a

learned monk, the piece of parchment may well have assumed a value related

to an esteem for written works as objects of worth rather than to the content

of the words. A similar psychology may apply to the practice of recording

legal transactions in a blank leaf of a gospel

book, the Biblical

reference underlying the solemnity of a transaction under oath and the book

itself serving as a ceremonial object of value. |

|

continued  |

The

Concept of Literacy The

Concept of Literacy |

|

|

|

|

|

|