If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Travel Literature (3) | |||

| The story of The Voyage of St Brendan is one of a genre of Irish stories of heroic sea voyages which date from around the 7th, 8th and 9th centuries. Some of these were secular in nature, but that of St Brendan is presented as a highly structured Christian allegory. The period in which the work was produced was one in which Irish missionaries were undertaking journeys to convert the pagan populations of Europe, but this journey goes to a very different land, revealing many wonders on the way. St Brendan evidently existed, living in the early 6th century and founded a number of Irish monasteries. The journey is supposed to begin at the monastery of Clonfert. |

|

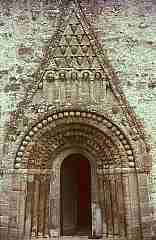

||

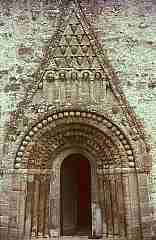

| A Romanesque doorway at Clonfert, dating from many centuries after St Brendan's time. Photograph by John Tillotson | |||

| The work was very popular, and appeared in many parts of western Europe in the original Latin and in vernacular translations, and even in new versions. Over the centuries the interest has been maintained, with fascination for the asceticism and piety of the monastic voyagers being replaced by more modern questions. Can the places described in the story be stripped of their allegorical covering to reveal genuine geographical locations, and did St Brendan sail to America? | |||

| That indefatigable historical voyager Tim Severin accomplished the feat of sailing to America in a small wooden framed boat covered with ox hides smeared with fat, as described in the original. He became convinced the the Island of Sheep was in the Faroes, that the Island of Smiths represented the volcanoes of Iceland, that whales could be represented as sea monsters and that icebergs could resemble pillars of crystal. In other words, it was all possible, but most unlikely that it represented a single voyage. | |||

| It is an artifice of storytellers to combine multiple strands into a single tale with a named hero. One really good yarn is worth a dozen bits of stories. The Irish monks may have been protagonists of literate Christianity, but they also came from a culture of oral storytelling and legend. There is no proof, outside the story itself, that Irish monks voyaged so far, but there is evidence within the text of a great deal of knowledge of places and phenomena of the northern Atlantic seas. So does this make it truth or fiction? As the French say, "Comme çi, comme ça". It's a great medieval travel story. | |||

| A translation of the original can be found in O'Meara, J.J. 1978 The Voyage of St Brendan: Journey to the Promised Land New Jersey: Dolmen Press. The re-enactment is described in Severin, T. 1978 The Brendan Voyage London: Hutchinson & Co. Then there is the video, not to mention the specially composed music for uillean pipes and orchestra because the whole story inspired an Irish musician to revel in his cultural heritage. | |||

| A similar conception applies to the Icelandic sagas which describe in heroic terms the voyages of Scandinavian adventurers to a place called Vinland. The sagas were probably not written down until the late 12th to mid 13th centuries, at least 150 years after the events they portrayed, during which time they were elaborated and honed by the oral storytellers into suitably ripping yarns. The oldest surviving texts are some two centuries later than that. | |||

|

Viking vessels were perfectly capable of undertaking long voyages over open ocean, and did. | ||

| The archaeological site of l'Anse-aux-Meadows in Newfoundland lends some evidence to the argument that Viking settlers may have travelled that far. However, that does not mean that the Vinland sagas are to be taken too literally in every detail. They are part of an originally oral tradition, the function of which was to entertain, amaze and provide a traditional foundation for ethnic identity and values. Take the bare bones of a story, and make a good long winter's evening out of it. The suspicion that some details may be confused, conflated or embellished does not deny the possibility of some underlying truth. The discovery of evidence for that underlying truth does not make the saga stories literal fact. | |||

| Read all about it in Magnusson, M. and Palsson, H.1965 The Vinland Sagas: The Norse Discovery of America Harmondsworth: Penguin. A genuine piece of manuscript saga text from the late 14th century has been put on the web by Det Arnamagnæanske Institut of Denmark. | |||

| Such storytelling devices were not confined to tales with origins in preliterate traditions. The most famous medieval travel story of all, the 13th century tale of the journey of Marco Polo from Venice to the court of the Great Khan in the Mongol kingdom of China, exists not only in a great number of extant manuscripts, but in a great number of different versions. The story was supposedly originally dictated to a fellow prisoner when the traveller and the scribe had both got themselves into a spot of bother in Genoa. In the rewriting, bits have been left out, other bits added from the general stock of travel tales and things have become conflated with the works of other travel writers. There is no definitive core text. This was a popular tale, and it can only be surmised that it underwent the same transformative processes in the hands of storytelling scribes that oral tales underwent in the mouths of popular performers. | |||

|

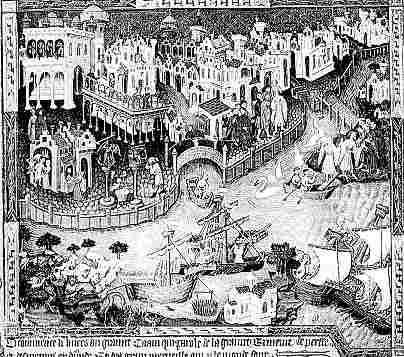

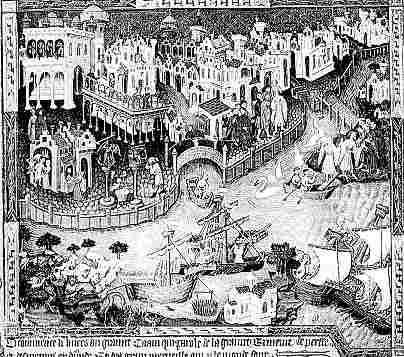

|||

| A much reproduced miniature of Venice, heading a manuscript version of The Travels of Marco Polo of c.1400 (Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 264, f.218). (From New Palaeographical Society 1905) | |||

| There are various editions of Marco Polo. Mine is an august old volume with lots of footnotes, Wright, T. (ed) 1892 The Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian London and New York: George Bell and Sons. | |||

| It is not unusual for medieval codices to contain a number of works on related themes. The collection of various works of travel in a single volume may have allowed the enthusiast for the genre to compare and contrast, abstract and consolidate. | |||

|

|||

| Prologue to a 14th century copy of a Latin version of The Travels of Marco Polo (British Library, Royal MS 14 C xiii, f.236). (From New Palaeographical Society 1908) | |||

| The above example is in a composite volume with Ralph Higden's Polychronicon, the works of Gerald of Wales on Ireland, the travels of Friar Odoric and Friar Willian of Rubruck, among other things | |||

| Given this storytelling tradition in travel literature, it seems a little ironical that a mysterious author who took it just a little bit further, an author writing under the name Sir John Mandeville, should be castigated for being a hoaxer and travel liar. The work first appeared in the mid 14th century and was rapidly translated into every European language. It was immensely popular and survives in around 300 manuscripts. The author claimed to be an English knight, but that is in doubt, as is the idea that he travelled anywhere at all. | |||

| Whether or not he actually travelled himself, he made lavish use of the works of previous travellers. He drew many tales from the writings of Friars Odoric and William de Rubruck, but added in monsters from the realms of Classical literature and baby-eating cannibals and all the dubious characters of the literature of the exotic. Furthermore, he did not present it as a compilation, but as a record of his own adventures from the eastern Mediterranean through to China. Still, given some of the conventions of this style of literature, and the compiling nature of the medieval literate tradition in general, perhaps it is a bit rude to call him a liar. It might be just a bit more fair to call him a storyteller. |

|

||

| A medieval ship for a voyage of the mind. | |||

| To find out what all the fuss was about, try Mosely, C.W.R.D.1983 The Travels of Sir John Mandeville Harmondsworth: Penguin. | |||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||