|

|

Travel

Literature (2) |

|

The

Christian religion had a sense of place. The origin stories of the religion

were rooted in the places in Palestine that figured in the gospel

story of the birth, life, death and resurrection of Christ. For the practitioners

of western Catholicism, it was never their own place. Not only did they

not live there, it was not part of their ethnic origin story. The practice

of pilgrimage to the Holy Land involved a journey to a foreign land to

find and establish a mental template for the significant places of the

foundations of Christianity. |

|

|

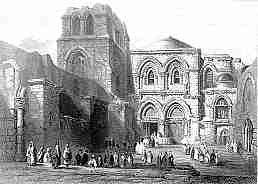

The

Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem. |

|

From

the earliest written works on pilgrimage to the Holy Land, dating from

the 5th century, to the works of late medieval pilgrims such as Margery

Kempe, there is a fascination with describing and enumerating the specific

sites associated with the Bible

story. Not only were there the places associated with such significant

events as the birth of Jesus, the crucifixion or his tomb, but legendary

places purporting to be a rock where Mary sat down when she was weary

on the road to Bethlehem, or a well where she quenched her thirst. Whether

these precise spots remained constant for a thousand years I have no idea,

but they provided significant nodes to fill out a spiritual map of the

origins of the religion. The readers who had not taken the pilgrimage

were given access to this mental template.

|

|

Not

all pilgrimages were to the Holy Land. As the middle ages progressed,

the practice of pilgrimage became more common. Sometimes this might involve

a modest journey within one's own country; on other occasions it could

be a major expedition. Travel was always difficult and hazardous, and

pilgrims' guides provided practical information about distances, modes

of travel and the availablility of food and lodging, particularly at the

specially provided hospices for pilgrims. |

|

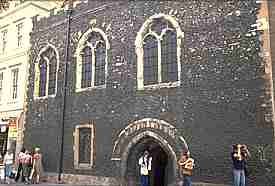

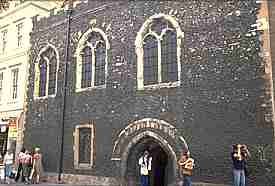

The

Pilgrims' Hospital at Canterbury, which catered for those who came to

visit the shrine of St Thomas a Becket. |

|

Apart

from the trip to the Holy Land, the great medieval pilgrimage was to the

church of Santiago de Compostella in northern Spain, where the remains

of the apostle St James the Great were supposed to be preserved. There

were several major pilgrimage routes across Europe which converged on

this site. Along these routes grew up a series of distinctive churches

with their own saintly relics, inns and hospices, and a culture of hospitality

to the stream of pious folk who travelled so hard and so long. |

|

|

This

tower is all that survives of the church of St Jacques in Paris, traditional

starting point for one of the major routes. |

|

St

James is depicted as a pilgrim himself, with hat and staff, in a 14th

century stained glass window in the church of St Mary, Castlegate, York. |

|

The

12th century Pilgrim's Guide to Santiago de Compostella,

which survives in several manuscripts, is a kind of Lonely Planet guide

for the faithful. It includes information about hospices and the peoples

encountered along the route. It gives a description of the many saints'

shrines which can be visited along the way. It warns of hazards such as

nefarious ferrymen. It concludes with a description of the town and church

of Compostella. This is not an armchair guide to situate the reader in

mental space, but a practical guide to survival and appreciation of the

journey. |

|

A

Christian motivation prompted other great journeys, extreme in their difficulty

and only to be attempted by those who were trained to asceticism and hardship,

Franciscans. Three accounts survive of overland journeys by Franciscan

friars to China during the period of the great power of the Mongols. These

were the journey of John of Pian de Carpini (1245-1247), William of Rubruck

(1253-1255) and Friar Odoric (1318-1330). It is probably unnecessary to

indicate that these good men did not manage to convert the descendants

of Ghenghis Khan to Christianity, or persuade them to offer their allegiance

to the pope. However, they described experiences and cultures that were

unknown to their brethren at home. The first two journeys predate and

the third postdates the much more famous journey of Marco Polo, but even

though the subject matter is as exotic, the accounts are plainer and less

embellished than that of their secular contemporary. |

|

This

image of the hut-wagon of the medieval Tartars being drawn by many beasts

is a visualisation of the description of Friar John. |

|

While

these writers had their own cultural perspective, their descriptions form

a competent ethnography. There are no one eyed monsters or grotesques

from the margins of the mind. Friar Odoric journeyed even further, to

Sumatra, Java and the coast of Borneo. While he falls for that old informant's

fib about human flesh being sold in the marketplace like beef, he also

gives a very accurate description of the manufacture of sago and the use

of poisoned arrow tips. On some other matters his interpretation may seem

a trifle credulous, but then he didn't have a library of comparative material

to swot up on in preparation for his journey. |

|

There

was a predecessor to these observant wanderers, although one whose observations

were taken much closer to home. In the 12th century, Giraldus Cambrensis

or Gerald of Wales, a cleric who was by birth three parts Norman and one

part Welsh, undertook journeys through Wales and Ireland. These close

neighbours to England supported modes of living, quaint customs and beliefs

in wonders that could be as exotic as anything from the remote east. Nevertheless,

Gerald himself felt compelled to justify his need to write about his own

native land, on the basis that there was not much he could add to such

respectable themes as the fall of Troy or the history of Athens, but he

could make a genuine contribution to knowledge in this way. |

|

Gerald's

writings on these subjects combine topographic description, little episodic

bits of local history obtained from local informants, sparse historical

notes derived from annals

and chronicles,

as well as his own personal observations of natural history and of the

behaviour and habits of the people. He tells us that the Welsh have a

passion for part singing in harmony and the Irish all play musical instruments

on every possible occasion; ethnic stereotypes that are perpetuated to

this day, not least by the Welsh and Irish themselves. |

|

|

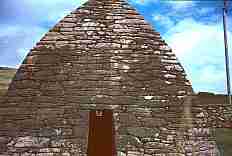

The

oratory of Gallarus at Dingle, Ireland. Even the built landscape of Christianity

was foreign in Ireland. |

|

Gerald's

commentary may seem a little credulous to us today, and some of his observations

highly inaccurate. Being a medieval churchman, he dutifully recorded the

multitudes of miracles performed by revered objects or at special sites.

He was, perhaps, a little susceptible to some fairly dodgy stories told

to him by informants. His natural history was defective, but some parts

were, nevertheless, based on his own observation. When he reported that

a certain species of geese hatched from the barnacles found on floating

logs in profusion where the geese resided, he was hypothesising on the

basis that nests or eggs of these birds had never been found. Neither

he nor anybody else knew about the migratory habits of birds that nested

on distant shores. |

|

Gerald

reported on the numbers of sacred and miraculous ancient bells and croziers

in Ireland. |

|

|

|

A

priest administers the Eucharist to a wolf while its mate helps out with

the reading, and an Irish king is consecrated sitting in a stew made from

a newly slaughtered mare in marginal illustrations depicting the text

of some of the more dubious tales in a late 12th century copy of the works

of Gerald of Wales on Ireland (Britsh Library, Royal 13 B VIII). By permission

of the British Library. |

|

Despite

these eccentricities, Gerald's descriptions give an insight into what

Wales and Ireland were like, and even more, how they were perceived to

be. The prejudices in the text are the prejudices of their time. The inaccuracies

themselves shed light on the thought patterns of the time. Gerald's animal

and bird descriptions became incorporated into the bestiaries,

in that typically medieval pattern of integration and reincorporation

that made medieval literate culture grow like a rolling snowball. |

|

The

works of Gerald and the travelling Franciscans are sober accounts, despite

the amazing nature of their content, complete in a one generational text.

Another whole genre of medieval travel literature consists of multigenerational

texts in which multiple oral retellings eventually get written down and

are then reincorporated into new accounts until truth and fiction are

indistinguishable and the story is more important than the facts. |

|

continued

|

previous

page previous

page |

Categories

of Works Categories

of Works |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|