If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| The Concept of Text in the Manuscript Tradition (4) | ||||

| In other sections in The Content of Books I have provided a very concise, terse even, look at the complex relationships between chronicle history and romance in medieval literature, and indicated the the distinction between fiction and non-fiction is not strongly drawn, as the two categories mutually intertwine. The examples have been drawn from the legend of King Arthur, but this is in no way a unique case. | ||||

| The most sober of chronicles, even those without wizards and magic swords, often followed the medieval tradition of starting from a common received text. Any story could begin with the seven days of creation and cruise fairly rapidly through some major events of history, before settling down into the particularities of recent events, recorded as they happened and reflecting events of local significance to the institutions in which they were written down. Different manuscripts are not direct copies, but form diverging families of text. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is one example of this, as is the Brut, originally the English version of Geoffrey of Monmouth's epic, but containing assorted continuations and variations into recent medieval events in different copies. | ||||

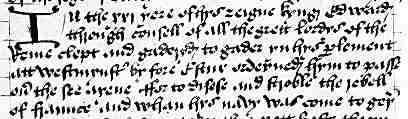

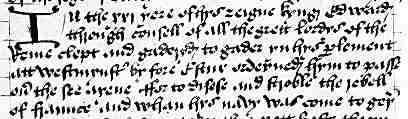

|

A little grab from a manuscript of the Brut, detailing events in the reign of Edward III (British Library, add. ms 33242, f.141), by permission of the British Library. | |||

| Chronicles also served as foundation documents, establishing the identity and origins of the institutions in which they were created. The inclusion of mythology from the medieval corpus to encourage pilgrimage was a part of the medieval economy. Santiago de Compostella did very well out of the legend of St James, as described by Jacobus de Voragine, and Glastonbury Abbey did very nicely out of King Arthur. Modern librarians may have had trouble with the classification of texts which we loosely refer to as chronicles. | ||||

|

||||

| The ruins of Glastonbury Abbey. | ||||

| The literature which was commissioned by and for the laity also had its agendas. The aristocratic texts of romance are subject to a continuing and continuous process of addition and variation for a number of reasons. The simplest of these is that there is no particular reason why one text of a romance should be identical to another. There is no presiding authority to ensure it, and perhaps a certain prestige in commissioning a unique work to flaunt in communal readings with one's social peers. The major cycles of romance; those derived from stories of the ancient Classics, those derived from Arthuriana and those derived from French or Breton legend; acquired increasing casts of characters and additional story elements as the texts evolved and developed. Like the monastic chronicles, they also could serve a function as foundation legends of aristocratic families, and family histories, real or legendary, were woven into them. | ||||

|

||||

| A marginal illustration from a French language romance of the early 14th century. The full work is Le Roman de Saint Graal, in 3 volumes, and this illustration comes from the first folio of Le Roman de Lancelot du Lac (British Library, add. ms. 10293, f.1). By permission of the British Library. | ||||

| The addition of Sir Lancelot into the Arthurian legend, as above, takes the tales from affirmations of British identity to appropriation into medieval France. | ||||

|

Another aspect which aids the fluidity of such texts is their relationship to oral performance through the chansons de geste of the jongleurs. While the performers undoubtedly learned their lines and songs, the nature of such performance lends itself to constant variation and innovation. Songs and tales did get written down, but probably only a tiny fraction have survived. The posh aristoctratic productions represent one end of the spectrum in relation to production values, and are most likely better represented numerically as the volumes have been curated over the centuries as treasures. | |||

| A jongleur, as depicted in a manuscript of performance poetry. | ||||

| The fact that stories often appear in families, such as the multiple variations and evolution of the stories of Reynard the Fox, indicates that they are appearing out of a tradition of oral performance which includes innovation and the recombination of existing elements, rather than from a sequential copying of what are perceived to be correct texts. Certain texts became part of the literate tradition and were copied on, but they were part of a much more complex tradition, and nobody would accuse a writer who borrowed a few characters and traditional elements to write a new story of plagiarism. It was how it was done. | ||||

|

An illustration from a story of Reynard, giving more than a little hint of satire of the courtly romance (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, ms. franc. 1581). | |||

| Accidents of survival may colour our perception of medieval text. For example, there is only one surviving manuscript of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Modern editions can carefully check the transcription, modernise the spelling and add copious footnotes to the one authentic text. We will never know how many stories of green mythic humanoids or other weird phenomena derived from folklore and grafted to the romance tradition were touring around the English midlands. If they entered the literate tradition, they became lost. The authentic and unique text is a modern construct. |  |

|||

| Illustration from the manuscript of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in the British Library. Never was there a dinner party like it. | ||||

| At the other end of the spectrum, the tale of The Travels of Marco Polo survives in hundreds of extant copies and many different versions. While the story commences with the sober assertion that it was written down by a fellow prisoner while the eponymous hero was doing a stint in jail in Genoa, the multiple texts are full of variations and borrowings, as if the basic story served as a scaffolding for all the travel yarns of the middle ages. The whole variety and assemblage becomes a sort of meta-text. The authentic story of one man's travels may be impossible to tease out, but all the variants contribute to an authentic medieval European vision of exotic places. | ||||

| Then there is the issue that the author of a work distributed in manuscript form was not constrained from altering it himself. | ||||

| |

||||

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||