If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| The Concept of Text in the Manuscript Tradition (3) | ||||||

|

While the church had a not undeserved reputation for being prescriptive, there was some range of choice in the way texts could be used. The liturgy was not absolutely determined by central authority, and different dioceses used various selections or combinations of texts to make up their liturgical works. Breviaries, for example, are described as being for use of Rome, use of Paris, use of Sarum (Salisbury) or other. Each of these uses had their own selections of Psalms, readings, prayers and smaller elements for the various parts of the divine office. The selections were drawn from standard texts, mainly Biblical, but they were assembled in variant ways. | |||||

| A segment from a 15th century breviary from Spain, for Carthusian use, from a private collection. | ||||||

| The lay version of the divine office, the book of hours, was assembled with even more freedom of choice. Even with the main Hours of the Virgin, there may have been more variation in the selection of the text than the term "use" implies. As well, the choice of other texts within the book could be very much at the desire of the individual client. People chose their own selection of prayers and devotions, and their own collection of saints to whom they offered prayers. Even the calendars could contain a different selection of saints' days for commemoration, although the major feasts of the church were always represented. |  |

|||||

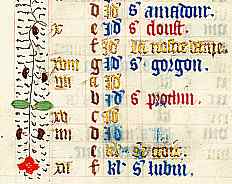

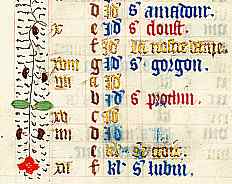

| Segment of a calendar page from a French book of hours, from a private collection. | ||||||

| The feasts listed above include a bishop of Bruges, a priest and confessor of Paris, the Virgin Mary, two early Christian martyrs, the Holy Cross and a bishop of Chartres. The assortment has a geographical bias towards the northern part of the French speaking world. | ||||||

|

Books of hours were also produced in vernacular languages, making them more accesible to lay readers. The prayer at left, in the Dutch language, makes reference to the crown of thorns, apparently something of a speciality of Dutch texts. | |||||

| Segment from a Dutch book of hours, from Haarlem in the later 15th century, from a private collection. | ||||||

| The selection of saints' lives, stories, legends and even the iconography of the illuminations in these texts depends on the development over the centuries of a textual tradition of appropriate religious literature, passed through the filter of official approval but able to be selected in various permutations and combinations. How this corpus developed is rather complex and, to a great degree, ill understood. | ||||||

| It is slightly irritating that studies of certain religious texts, such as the New Testament Apocrypha or the lives of early saints, seem to concentrate heavily on locating the oldest versions of certain texts in order to give them some authenticity. When certain legendary stories have first appeared in Coptic texts from Egypt or Armenian texts, as has been the case, one is still left with a bit of a mystery as to how these texts developed and were transmitted to appear in later medieval religious literature and art. Because more is lost than has survived, routes of transmission can be blurred. The fact remains that much legendary material concerning the holy family and the saints was transmitted, with many embellishments and accretions, and recombined with other stories, to reappear centuries later. Their authenticity as Christian texts for their time was based, like the works of scholars, on their being grounded in an ancient written tradition, but they were not required to be uncorrupted, unadorned ancient texts copied unaltered from ancient times. They were ratified by their context. They provide much of the iconography of western Christian art in the churches and cathedrals. Learned scholars mined them to produce teaching texts for the laity, such as the mystery plays. | ||||||

|

Works on the lives and deaths of saints had been in the Christian tradition since the earliest of times. It was common to depict saints carrying their attributes, or scenes of their life and martyrdom, in the stained glass, wall paintings and sculptures of churches great and small. A work of the late 13th century, which came to be known as The Golden Legend, provides an interesting example of the medieval approach to text, and to our modern appraisal of it. |  |

||||

| Saints depicted in the 14th century stained glass of the Benedictine church of St Pierre in Chartres, a diversion from the more famous cathedral not to be missed. | ||||||

| The work was originally written by an Italian Dominican known as Jacobus de Voragine. It included the lives of many saints, and episodes or details from the life of Christ and the holy family that are not to be found in the gospels of the New Testament. He did not make it up, but in fine medieval tradition mined many ancient sources, some of which he himself suggests are apocryphal. It was one of the most popular works of the middle ages, and around one thousand manuscripts of it still survive. It was possibly the largest single influence on late medieval church art. Popular, but almost entirely legendary, saints like St Christopher and St Ursula spring from his pages. |  |

|||||

| St Christopher, shown here in a miniature from a 15th century book of hours from northern France (Vatican Library, Cod. Vat. Lat. 14935). From a facsimile. | ||||||

| A modern English translation of this work (Ryan 1993) is based on a Latin text published by Th. Graesse in 1845, based on a manuscript in the Royal Public Library in Dresden, which included 182 chapters identified as the work of Jacobus and 61 by other authors. The English translation includes only those chapters deemed to be original texts by Jacobus. An early English translation produced by the printer Caxton omitted some of the chapters deemed to be by Jacobus, but included some English and Irish saints. Here we see the modern concept of a definitive and authentic edition at war with the medieval organic concept of a text. Just as calendars in breviaries, psalters and books of hours could contain different selections of saints, so could The Golden Legend, even when it was parading as the work of a particular author. To my knowledge, a full examination of the variations on The Golden Legend in surviving manuscripts has not been carried out. It would make a fascinating study in how text was transformed and appropriated. There is no real question of any one example being more authentic than another. They are all authentic witnesses to their time and place. | ||||||

| No matter how many permutations and combinations they appeared in, religious works were always passed through the filter of church approval, which makes textual variation something of a process of selection from a smorgasbord. In the later middle ages, books produced for the laity, or even in some cases for non-liturgical purposes for the clergy, were not subject to such scrutiny. Text becomes an even more dynamic entity. | ||||||

| |

||||||

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||||