If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Romance (2) | ||||||

| Perhaps the most interesting series of romances, from the perspective of integration of genres of writing, is the Arthurian cycle. Here history and romance become so entangled that it becomes difficult to know which is which. If you have already read the section on Histories, Annals and Chronicles, you will know that King Arthur was essentially invented by Geoffrey of Monmouth in the 12th century. He claimed he had obtained all his information from previously unknown written sources in the British language, but even some of his contemporary historians doubted him, and accused him of writing fiction. | ||||||

|

Geoffrey's work hit the mark, however, and became the defining legend of the British people. It was translated into Norman French and also into English, with a few extra stories thrown in, when it was known as the Brut. This became the starting point for many sober English chronicles, which lacked any later references to wizards, prophecies or swords in stones. They did describe how Edward III founded a round table, however, indicating how far the legend had become embedded in concepts of English kingship. | |||||

| Pulling a sword from a stone is child's play compared to attempting to unravel the Arthur literature. | ||||||

| In 12th and 13th century France, the story took a different twist. There storytellers used the tale as the basis for a new and entirely fictional literature of chivalry. Some of the well-known characters of the legend, like Sir Lancelot, entered the cycle at this time. The stories were no longer origin myths of the British people, but elegant reflections of courtly life in high medieval France. Like oral stories, they had a life of growth and diversification and borrowing and reiteration. | ||||||

| The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley displays some images from a late 13th century manuscript of Mort le Roi Artur (UCB 073). | ||||||

|

||||||

|

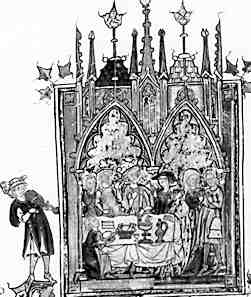

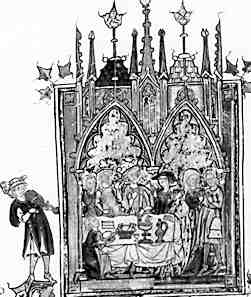

Above, a marginal illustration and on the left a miniature from a French language romance of the early 14th century. The full work is Le Roman de Saint Graal, in 3 volumes, and these illustrations come from the first folio of Le Roman de Lancelot du Lac (British Library, add. ms. 10293, f.1). By permission of the British Library. | |||||

| The images above show how the story has escaped from its British origins and into 14th century aristocratic France. The miniature shows an elegant dinner party in a Gothic hall, with a minstrel playing his viol in the margin to the left. The marginal illustration from the top of the page shows two knights in combat, on horseback with lances and shields. There is also the usual assortment of 14th century marginalia, including a faded and smudged image of two people in intimate bodily contact on a hill with a tree on top. Maybe somebody from a more puritanical age has tried to obliterate that one. | ||||||

| While the English were adopting Geoffrey of Monmouth's fiction or legend as history, the French were creating an array of unabashed fiction from this base. There were few Arthurian romances written originally in the English language, but the well known 14th century poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, written in a midland dialect, seems to bring in another strand. It has King Arthur and his knights, feasting, honour and chivalry, but it also has a strange supernatural knight who is actually green, huge and can gallop around on his horse shouting out challenges after his head has been cut off. There has been much ink expended on the symbolism of this work, but the green knight himself seems to have escaped from an undocumented folkloric tradition that also produced the green men and wodewoses, or hairy wild men, that sometimes appear, tamed and Christianised, in church carving. |

|

|||||

| A green man with leaves issuing from his mouth on a carved misericord in the formery nunnery church of Swine, East Yorkshire. | ||||||

|

||||||

| A misericord depicting a hairy wild man among lush foliage in Chester Cathedral. | ||||||

| If one is thinking in purely medieval mode, one might say that this whole body of Arthurian literature reached a climax with Malory's Morte d'Arthur in the late 15th century; a work which compiled much from previous examples of the genre. However, that would be to ignore Alfred Lord Tennyson, Sir Walter Scott, J.R.R. Tolkein, the odd opera by Wagner and a whole bunch of movies from the sublime to the ridiculous. And did you know that Shakespeare's King Lear is derived from one of the lesser known bits of Geoffrey of Monmouth, not actually concerned with Arthur? Great stories never die. | ||||||

| Folkloric stories of the strange and supernatural, with fairy-like characters and weird creatures, also contributed to the Continental romance literature. French romance writers were quite unabashed about pillaging these stories from other cultures. German vernacular romances were also derived from the oral folklore tradition, the most famous being the epic Nibelungenleid. Both Wagner and Tolkein found their muse in these as well. These ancient tales sometimes became transformed to fit them into the genre of the Arthurian or Carolingian mode, so that the retinues of these legendary men picked up wandering Welshmen, Bretons and Danes from other stories and transformed them into chivalric knights. | ||||||

| The production of these upper class volumes did not stop people singing, reciting and telling stories, of course. Sometimes ballads and songs were recorded in writing, and not necessarily in the elaborate editions of the expensive romance codices. | ||||||

|

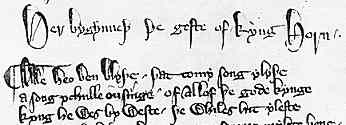

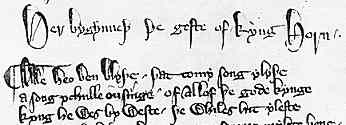

The beginning of the Gest of King Horn, in a volume of mixed poetry and prose of the early 14th century (British Library, Harley 2253, f.83). (From New Palaeographical Society 1911) | |||||

| The above example is written in a cursive book hand and the page is simple and unadorned. A series of works of poetry and prose in English, French and Latin follow directly on from one another. A published edition of King Horn was compiled from this and two other manuscript versions. This perhaps represents a middle area of the spectrum between the literate tradition of romance and the oral tradition of storytelling, which, in the age of handwritten texts that could vary from one version to another, had much more in common than they do today with our obsession for the "correct" version of any written work. | ||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||||