If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Exchequer Records (2) | |

| The oldest surviving rolls are the Great Rolls of the Exchequer, also known as the Pipe Rolls, produced by the Upper Exchequer. The oldest dates from the end of the reign of Henry I, of 1129 to 1130. The complete series begins with the second year of Henry II, 1155 to 1156. The rolls were written in a formal and careful script, and were evidently drawn up in advance so that the figures could be entered into them. Much is repetitous, as they record ongoing bad debts and recurring fixed annual payments by the sheriffs, as well as new transactions of each year. There is now an extensive body of these documents in modern printed editions. | |

|

|

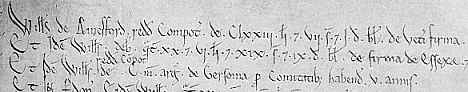

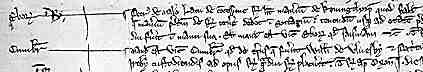

| A little sample of the script of the Pipe Roll of 1130 (National Archives, I, m. II). (From Johnson and Jenkinson 1915) | |

| This early example of the Exchequer hand shows a formal and rather rounded script, showing its close relationship to Caroline minuscule, but with certain individual little extravagances of style. | |

|

|

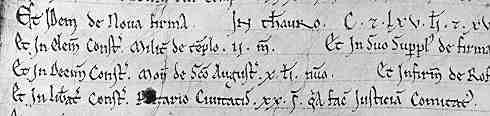

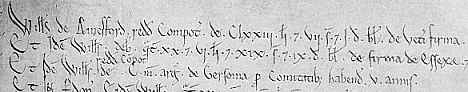

| Another sample, this time of the script of the Pipe Roll of 1167 (National Archives, 13, m. 13). (From Johnson and Jenkinson 1915) | |

| In this slightly later example, the script somewhat resembles a protogothic book hand. Note various examples of the st ligature, which for some obscure reason always seems to denote a formality of writing. It is certainly a very clear and spacious hand, especially compared to the catscratch that they would produce on the Chancery rolls. The Great Rolls of the Exchequer continued until, would you believe it, 1833. | |

| As with the Chancery, business become too complex and multifarious to be all included on one set of rolls, and the records proliferated. The Lower Exchequer produced Issue and Receipt Rolls, recording for posterity the transactions for which tally sticks were issued as receipts. | |

|

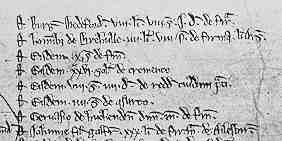

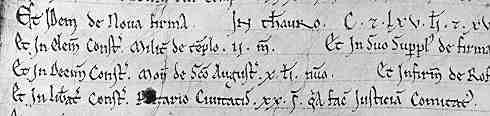

A segment of writing from the Receipt Roll of 1233 (National Archives, 10, m, I). (From Johnson and Jenkinson 1915) |

| The script above is neat and legible enough, but small and cursive, with curly ascenders typical of 13th century document hands. It is more of a working document than a majestic archive. | |

| By the mid 14th century, the rolls of the Upper Exchequer were separated into foreign accounts and special series for customs, taxation and various other particularities, as well as the series of monies tendered by the sheriffs. The Memoranda Rolls recorded unfinished business, and were produced for officials with the marvellous names of Lord Treasurer's Remembrancer and King's Remembrancer. These names, in my humble opinion, hark back to times when there were people whose job it was to remember things for other people, rather than having the luxury of reading what had been written down for them. These recorded such matters as court cases in which the king, or rather the crown, had some financial interest. | |

|

|

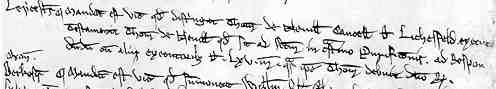

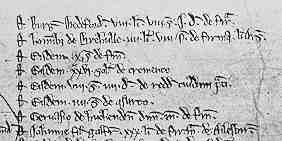

| A snippet from the Memoranda Roll of the King's Remembrancer for 1219-20 (National Archives, Memoranda Roll 3). (From The New Palaeographical Society 1914) | |

| The tiny and simplified cursive hand of the above example is starting to look almost scruffy. | |

| While Chancery and the Exchequer functioned as two separate departments, or sets of departments, they had certain interests in common. The Originalia Rolls are extracts from the Chancery Rolls containing copies of writs, letters and charters on which fines were payable to the crown. | |

|

|

| And another tiny snippet from the Originalia Roll of 1232-1233 (National Archives, Originalia Roll 2). (From The New Palaeographical Society 1914) | |

| The Exchequer also held copies of Inquisitions Post Mortem, or enquiries concerning the assets of feudal tenants in chief at their death, from the Chancery, and extracts from the law courts which were relevant to the collection of monies. The Wardrobe and the Chamber, departments of the king's Household which remained with him at court, not items of royal furniture, have left few records of their own for reasons unknown, but evidence of their activities survives in the various rolls of the upper Exchequer, where they were audited. | |

| This all adds up to one big pile of records, and one might think that historians would be supplied with everything they needed to know about the financial affairs of the nation. Unfortunately, the records are not so easy to decode. From certain eccentricities of dating, to the fact that the recording of matters was a bit miscellaneous and all kinds of transactions have been recorded together on the rolls, to changes in the organisation of the recording system over the centuries, to the fact that medieval accounting was organised in a completely different way to modern accounting systems, all combine to mean that this is a job for real specialists. Even if you can read the writing, there is so much more to understand. All these records are preserved in the Public Record Office, London, now The National Archives. | |

| From the perspective of the increasing valuation of the written word, this proliferation of archiving is a phenomenon in its own right. While the records were being produced in a stable form that was, perhaps, seen as lasting for enough decades to see any affair or dispute to its conclusion, it has provided much more than a snapshot of the whole mentality of financial administration. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|