If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Borough Charters | ||

| A borough charter was a document granting rights or privileges, not to an individual or to a religious body, but to a community, namely a town. In the later part of the middle ages, the monarch granted to town corporations the right to a certain amount of self-determination, including the right to hold courts. This process was not simple and was not a generic procedure, but involved the specification of particular rights and laws in each individual case. Even at this level there could be complexities, as large ecclesiastical bodies such as cathedrals or collegiate churches might control a liberty, or specified area of the town where they oversaw criminal justice and were not responsible to the town authorities who ran the rest of the area. | ||

| The matters covered in a borough charter were those that were particular to town, rather than rural life. As well as the administration of justice, this included the right to build town walls and control the ingress and egress of persons to and from the city. Town walls might have had a military function in an emergency, but their more usual role was in defining the limits of the town and controlling entry. This function was more related to the control of trade and the exclusion of criminals, runaways or other dubious characters. |  |

|

| The walls of York have medieval origins, but they define the character of the city to this day. The long barbican which survives on Walmgate Bar was part of the system of control of entry. | ||

| Other matters particular to town life involved the regulation of markets, the capacity to levy tolls and taxes on travellers and traders and the regulation of guilds and the practices of tradesmen. The privilege of control over such matters was specified in the borough charter. There were supposed to be responsibilities as well, such as for the maintenance of roads, but standards of urban infrastructure management were evidently less than exacting. | ||

|

Norwich Castle provides a wonderful platform for panoramic views which show the medieval layout of the city. The view shows the area around the marketplace. | |

| The area shown above had its origins in the founding of a so-called French Borough after the Norman Conquest, outside the old Anglo-Saxon town. It is the heart of the area of trade and commerce, where the town guilds exercised their greatest infuence. The marketplace with its rows of stalls stands in front of the modern town hall, with the large late medieval church of St Peter Mancroft on the left, and on the far right, the late medieval guildhall. The streets of various artisans were arranged around the marketplace area. | ||

| Like other charters, a borough charter was very much a ceremonious object, designed for looking impressive while being read aloud in public pronouncement and for preservation by the town corporation as a significant artifact. However, borough charters were proliferating around the 13th century at a time when the written word was taking precedence over memory and oral tradition in the ratification of matters of law. Where an old fashioned land charter to a monastery or individual might be vague and allusive when it came to the specification of exactly what was being granted, the necessity for precision in the specification of rights and privileges in these corporate charters meant that they could sometimes be large and wordy documents. | ||

|

||

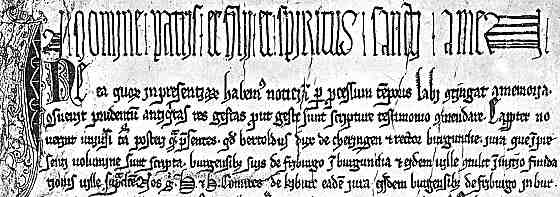

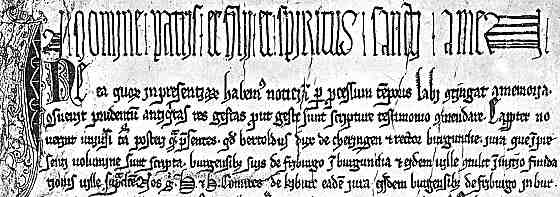

| First segment of a charter of liberties of Freiburg in Switzerland of 1249 (Freiburg, Kantonsarchiv). (From Steffens 1929) | ||

| The document above occupies three large sheets of parchment, held together by the cord of the ratifying seal. It is written in a formal diploma hand, which derives from a variant of a Gothic textura book hand, with a few calligraphic flourishes on the ascenders and descenders, giving it a most significant air. A very Continental feature is the solemn invocation on the top line, executed in a tall, compressed script. The highly embellished initial letter I and the n of the first word In and the laterally extended n of the final word amen on the top line all add to the importance and solemnity of the document. Its length indicates a fair degree of detail in the content. | ||

|

|

||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||