If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Dating Manuscripts (2) | ||||

| English legal documents, such as charters, of the earlier part of the medieval period, indeed into the 12th century, did not have the dates written on them. They must be dated using fiendish cunning and ingenuity and a great deal of highly specific historical knowledge. A royal charter gives you a head start if you know which king it was issued by. You don’t get a signature, but you do get a name, a bit of family genealogy and a seal. It makes a start. |

|

|||

| Seal of Henry I on a charter (British Library, Campbell Charters xxi 6). By permission of the British Library. | ||||

| Witness lists and references to people mentioned in the document can get you a good deal closer, but these must be approached as a kind of logic puzzle in which much highly specific data is employed. The general approach goes like this (in a hypothetical example): | ||||

| We have an archbishop of York named Ralph at the same time as an abbot of Leicester called William. Geoffrey was duke of Gloucester and his son Harry who died young was still alive as he also witnessed the document. There is a reference to Matilda, the sister of Walter, duke of Cornwall as if she is still alive and prayers for the soul of his first wife Agnes as if she is already dead. | ||||

|

||||

| Fish out the lists of dates of assorted bishops and abbots and the family histories of the dukes of Gloucester and Cornwall, plot it all up on a sort of bar graph and you may be able to narrow it down to a narrow time frame. | ||||

| The Chronology and Dating section of the Medieval English Genealogy website has some basic information on dating and useful links to reference sites containing lists of officeholders from chancellors to bishops. For some heavy duty essays on methods of dating English documents, try the Deeds Project. | ||||

| A royal document may contain a reference to where it was witnessed, if not when. Back to the records to find out how many times the king was in Dover at the same time as all the other conditions are fulfilled and it may narrow it down still further. | ||||

| Monastic documents may contain references to other members of the community and to specific office bearers. Correlating these into a bit of old fashioned historical narrative may allow documents to find their place in the chronological sequence through this cross referencing. | ||||

|

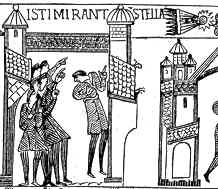

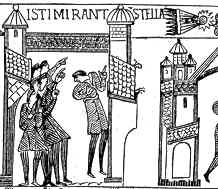

References to known historical events may be useful, but Halley’s Comet doesn’t conveniently come roaring across every time somebody wants to sell a couple of serfs. Usually it gets a bit more intricate than that. | |||

| Halley's Comet screams across the Bayeux Tapestry, presaging huge events in 1066. | ||||

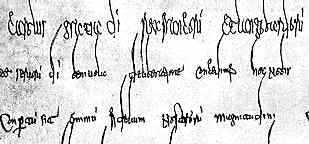

| Paleographical techniques can be applied to documents as well as books, but there are the same difficulties. Scripts do not change in a clockwork fashion. It is also necessary to know the particularities of the individual chanceries as house styles have developed and changed in different ways over the centuries. | ||||

|

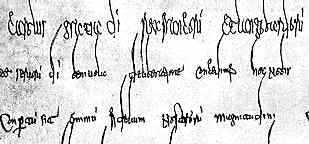

The distinctive tall script of the Merovingian chancery is here seen in a diploma of Charlemagne from AD 781 (State Archives, Marburg). (From Steffens 1929) | |||

| When dates do appear on documents in the later medieval period they are often entered in terms of the year of the reign of the monarch, at least in English documents. The trouble is, the year begins on the date that the king acceded to the throne, and old kings are not in the habit of conveniently dying on the 31st December. You need to know the date of succession as well as the year. Fortunately, people worked that out long ago and there are handy references available. (See Cheney 1970 or look on the web at the English Calendar.) In other countries, where the entering of dates in some form occurred from the early middle ages, one may find references to the regnal year of the Holy Roman Emperor, or of the pope. (Check out the Catholic Encyclopedia online or in hard copy or some other basic historical reference.) | ||||

| A dating clause given by regnal year in a note on a petition in the National Archives (E28/60/38), by permission of the National Archives. The king was Henry VI and the year was 1439. | ||||

| When conventional annual dates of the kind we are used to are utilised, there may still be some confusion as the year did not necessarily begin on 1st January. In fact, it began at different times, depending on where you were. (Look on the web at Calendar Tools to see some of the diversity.) | ||||

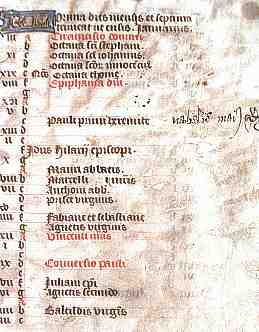

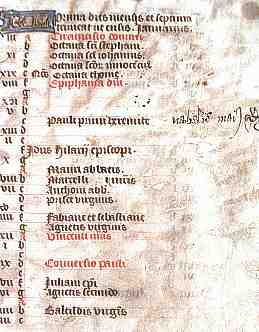

| The day of the year might not be given in terms of the day and the month. Saints’ feast days were the backbone of the church calendar and appeared in every psalter and book of hours. The date may be given in reference to one of these. Even more trickily, it may be given in relation to Easter, which was then, as it is now, a movable feast which occurs at a different time every year. As with the regnal years, these things have been handily packaged for our reference. (See Cheney 1970 or look on the web at the English Calendar or at the Medieval Calendar Calculator or at Glenn Gunhouse for a saints' calendar.) |  |

|||

| A calendar page from a 15th century book of hours (National Library of Australia, MS 1097/9, f.1r), by permission of the National Library of Australia. | ||||

| The day of the month may not be given as a simple number, but may be given in relation to the Roman designation; ides, nones, kalens. Now everyone must remember why Julius Caesar had to “Beware the ides of March”. (See Cheney 1970 again to sort this one out.) |  |

|||

| At the end of the day, it must be said that working out dates on medieval documents, even ones which have a date on them, is not entirely simple, but there are tools available to help you untangle the puzzle. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||