|

| Reading

a Calendar |

| The

way that time is measured and recorded reflects the needs and concerns of

a society. Among the villagers and peasants and country gentry of the middle

ages, time revolved around the turning of the seasons and their relationship

to the agricultural round. It was necessary to know the time for sowing, for

harvesting, for storing food for the long winter. It was necessary to work

lengthy hours in the long days of summer in order to store up resources for

the long nights of winter, enlivened with feasting and stories and foolishness.

As with all agricultural societies, this was related to the movements of heavenly

bodies; the sun, the moon, the planets and the constellations of stars. |

|

|

Among

the literate clergy, it revolved around the complex cycle of rituals and

feasts that made up the church calendar.

The missal and

the breviary,

as they became by the later middle ages, detailed an intricately varying

mode of celebrating the mass

and the divine

office, depending on the day in the calendar. The calendar itself

comprised interlocking sets of feasts or commemorations. A relic of this

which survives in our society is that we celebrate Christmas on December

25th, but Easter can fall on a different day every year. |

| A

liturgical calendar

became a major component of many religious manuscript

books, including the various works of liturgy, the psalter

and in the later middle ages, the book

of hours. The simplified office used by the laity and recorded in

the book of hours did not vary in the same complex way as that performed

by the clergy. The office was the same for every day of the year, but

the calendar served to indicate major feasts and saints' days. |

| While

the calendar in manuscript books was fundamentally for the recording and

computation of religious festivals, the concerns of ordinary people for

the seasonal round were not excluded. This was mainly expressed in the

decoration of the pages, which frequently included the signs of the zodiac

and depictions of the labours of the months. The zodiac signs have today

become a degraded form of popular culture, but they represent the constellations

which are seen near the horizon and which cross the sky according to an

annual sequence. They are used by agricultural societies in many cultures

and religions to plan their annual round of activities. |

|

|

|

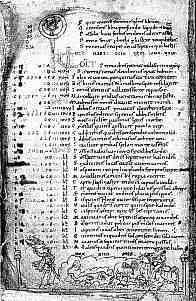

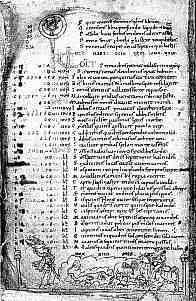

The

Julius Calendar and Hymnal (British Library, Cotton Julius A VI, f.7b), by permission of the British Library. |

|

This 11th century English work, shows the zodiac sign in the upper left corner and the labour of the month along the bottom of the page. The sign for October is Libra and the labour is hunting, which suggests upper class preoccupations here. Why a bunch of Anglo-Saxon lads are shown apparently hunting ostriches is a bit of an enigma, but suggests an exotic, probably Classical, source for the illustration. |

|

There

were two major cycles of feasts in the Christian calendar. The Temporal,

or Proper of the Time, included Sundays and all the feasts associated

with the life, death and resurrection of Christ. The whole cycle began

the week before Christmas with Advent and finished with the Ascension.

They were themselves divided into two groups. One group was based around

Christmas. These were held on fixed days of the calendar. The second group

revolved around Easter, which was a movable feast that occurred at a different

time every year. More about that later. |

|

| |

|

|

|

The

Ascension depicted in stained glass in the church of All Saints, Pavement,

York. |

|

The

second cycle was the Sanctoral, or Proper of the Saints. These were days

commemorating the saints, including the Virgin Mary. Some feasts, like

that of the Annunciation, were universal holy days of the church and celebrated

in all places. But there were multitudes of saints and nowhere did they

celebrate all of them. There were saints particular to local areas and

the calendars reflected the areas for which they were produced. St Bavo

was probably a bit of an unknown quantity outside Ghent although he appears

in Flemish manuscripts sold abroad, St Fermin was special to Amiens and

appears in northern French calendars and it is a mystery why a group of

churches in Picardy is dedicated to St Apollonia, patron saint of toothache

sufferers, but there will be a reason lost to history. |

|

The

Annunciation depicted in stone on an outer wall of Amiens Cathedral. |

|

|

As

well as being noted in the calendar and affecting the performance of the services,

these feasts were represented in the general visual culture of the church.

The events of the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary, depictions of the saints

and sometimes graphic depictions of their martyrdom were part of church art

in establishments great and small. Candles were set up in front of images

and they were venerated on their feast days, so they were a part of participatory

culture even for those members of the community who did not own a manuscript

with a calendar. The calendar directed the spiritual life of the community. |

|

continued |

Dating Manuscripts Dating Manuscripts |

Why Read It? Why Read It? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|