|

| Inks

and Colourings |

| One

of the arts of the medieval scribe

was the manufacture of his own ink. The illuminator

or manuscript

painter also concocted his own paints and pigments. This is part of a

vast compendium of craft knowledge from the middle ages which was not

necessarily written out in textbooks, as we would do it today, but which

was passed on as oral and practical knowledge, even when it was about

the construction of the written word. |

| There

were various formulations for ink, especially in the early middle ages,

but the most common concoction became that known as iron

gall ink. It used combinations of iron vitriol, or ferrous sulphate,

and oak galls mixed with wine, water or vinegar. Oak galls are swellings

found on oak trees caused by insect attack, and whoever thought that it

might be a brilliant idea to use them for concocting ink is lost to history. |

|

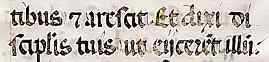

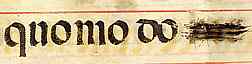

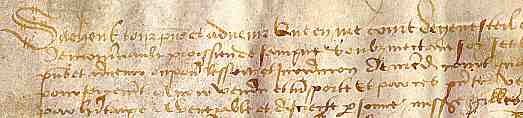

Iron

gall ink used in a 15th century book of hours (National Library of Australia,

MS 1097/9). By permission of the National Library of Australia. |

|

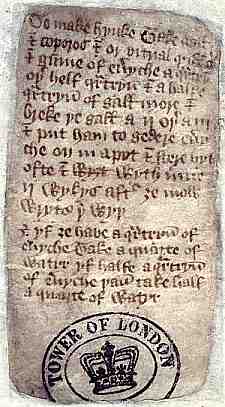

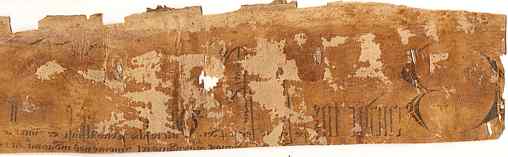

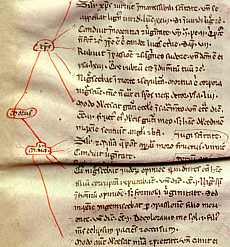

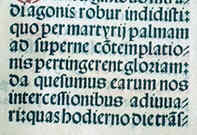

A 15th century recipe for ink (London, National Archives C. 47/34/1/3), by permission of the National Archives. |

| The medieval recipe at left basically says to break up galls and place them in a pot with vitriol, gum and water, stirring often. After two weeks it is ready for writing therewith. This scrap of parchment with 15th century writing is part of the Chancery miscellanea, which basically consists of oddments that were left over in the Public Record Office in London after all the official documents were classified. It must be presumed to be an official chancery recipe for ink. |

| Iron

gall ink tends to be a brownish colour, especially after it has been sitting around for a few centuries, although this can vary. A modern practical inkmaking scribe has informed me that all his iron gall ink always turns out black at first. (He offered to send me some to prove it, but I was a bit concerned about what customs and border security would make of mysterious murky substances!) Some formulations of ink seem to fade over the centuries to a quite pale brown, while others retain a vigorous blackness. |

|

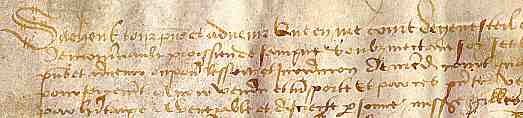

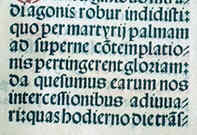

| Ink which has faded to pale brown on an early 16th century document from French Savoy, from a private collection. |

|

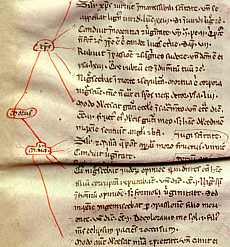

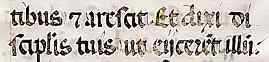

Ink which has remained resolutely black, despite the fact that the parchment has stretched and buckled under some sort of environmental stress, from a 14th century Italian work, from a private collection. |

| Whether the ink fades or not may depend on the conditions of storage over the centuries, and also on the original formulation of the ink. For some reason the colour of iron gall ink seems to be a hot topic of debate among modern re-enacting scribes, but if you look at writings which have been lying around for centuries, you will find a range from pale brown to black, and from solid coloured to faded or scrubbed. Certainly the fading is a sign of decomposition, but it happens. |

| The notable characteristic of iron gall ink is that it is acidic and it actually bites into the parchment of the page. On the one hand, this makes it very durable as it is difficult to erase and even if it fades or is partially obliterated, there is a trace burnt into the page which can be rendered visible. On the other hand, in humid conditions it can actually continue to work its way through the parchment and damage it, even making holes. |

|

Partially rubbed ink on page from a 15th century missal, from a private collection. |

| In the above example, the very black ink has been partially rubbed from the page in places, as in the top right of the example, but the writing is still perfectly clear because of the impression made on the underlying parchment. |

|

An erasure on a 15th or 16th century gradual leaf, from a private collection. |

| In the above example, an attempt has been made to actually erase a word, but as it remained firmly imprinted into the parchment, the corrector has resorted to some vigorous scratching out. It is still possible to see that the offending word is hic. |

|

| Sample of reversed writing from a papal letter of Benedict XII, from a private collection. |

| The example above shows something of the ability of iron gall ink to penetrate. This fragment, only part of which is shown, was recovered from a bookbinding where numerous sheets of parchment from old documents and the like were glued together to make a thick hard cover. The writing is back to front, as the corrosive ink has been transferred from a piece of adjacent parchment and soaked into the glue, actually working its way from one parchment sheet to the adjacent one.. |

|

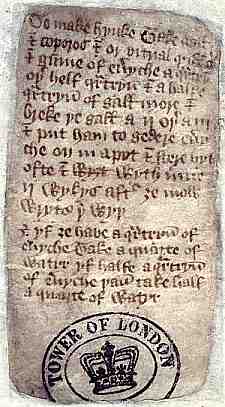

In

the later middle ages carbon

ink, made from soot and gum mixed with water, was sometimes used.

This formed a very black ink, but it simply adhered to the surface of

the page rather than bonding into it. Carbon ink was used in early printed

books. |

| Carbon

ink used on a leaf from a 15th century printed book. By permission of

the University of Tasmania Library. |

|

Tools

and Materials Tools

and Materials |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|