|

|

| Histories of Scripts in the English Royal Chancery (4) |

The legacy of medieval legal and bureaucratic process was in many cases long. The production of manuscript Parliament Rolls continued into the early 19th century. So did a form of legal process in which, in order to carry out a transaction, one party brought a fictitious lawsuit against another in court. The resulting legal agreement was written out as a final concord; a form of indenture in which a copy was retained by each party and another by the court. The process derived from the feudal system of land tenure which prohibited simple buying and selling of land outside the system of feudal tenure, but why it survived into the 1830s is a question you would have to ask a lawyer. What is intriguing is that an antique legal process should involve the retention of an antique form a handwriting. |

|

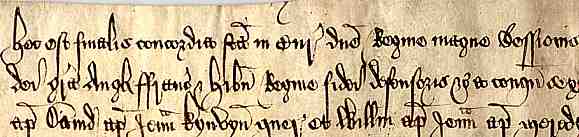

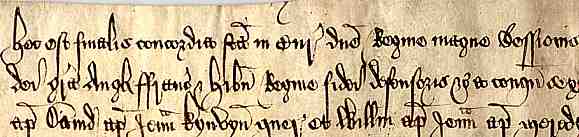

| Top left hand corner of a final concord of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of 1574, from a private collection. |

| The above example is a fine and splendid version of the bastarda style chancery hand of the chancery court from a time when certain other areas of the bureaucracy were adopting new styles. However, as styles become fossilised, they perhaps lose their logic and clarity. |

|

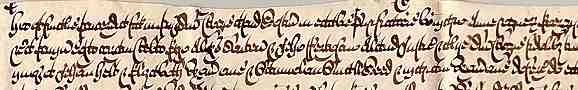

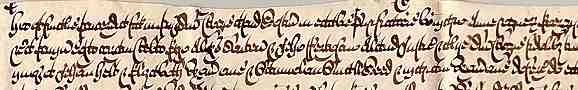

| Top left hand corner of an 18th century final concord, from a private collection. |

| The above example is from an 18th century final concord but the script, while clearly a descendant of the chancery bastarda, has become strangely loopy and incomprehensible. Apart from the fact that it begins Hec est finalis concordia (which I think I can only make out because I know that that is what it is supposed to say) and that the king is called George, about all I can pick out are a few names. A user of this website once sent me a picture of one of these from the reign of Queen Anne, which not only displayed the antique script, but used the medieval term messuage for a parcel of land. |

| The limited set of examples shown here can give only the barest outline of the script styles used in the English chancery. Writing is infinitely variable, so that at any given time, no two scribes write exactly alike even if they are following similar models for their script. As styles change, there are overlaps and hybridisations between old and new forms. For this reason, some paleographers of document hand have been unwilling to use classificatory terms for the changing scripts. Others have had a crack at it, but their schemes are not always entirely compatible, let alone in agreement terminologically. Like any other family of scripts, reading them requires some preliminary work in familiarisation with the basic letter forms, abbreviations and standard terminology of the various types of documents. |

previous page previous page |

History of Scripts History of Scripts |

What is Paleography? What is Paleography? |

|

|