If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Histories of Scripts in the English Royal Chancery (3) | |||

|

|||

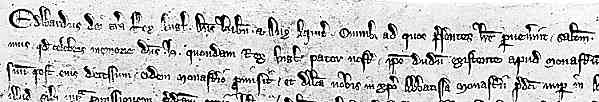

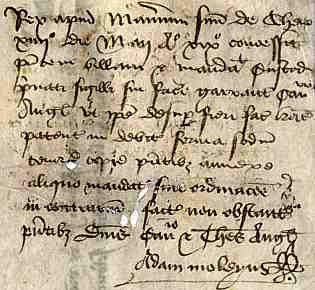

| Segment of letters patent of Edward I of 1291 (Westminster Abbey Muniments 6318B (From New Palaeographical Society 1909) | |||

| The above example, from letters patent in which King Edward I announces that he has delivered his late father's heart to the abbey of Fontevraud, shows the most formal usage of cursiva anglicana in a Latin document of the late 13th century. Ascenders are no longer exceptionally tall and the whole thing has a mannered loopy appearance. Split ascenders look like little palm trees. | |||

| The less formal script of writs and internal chancery documents also gradually changed from spiky to loopy. | |||

|

|||

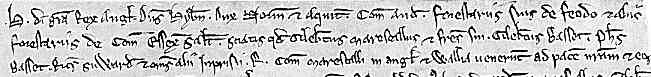

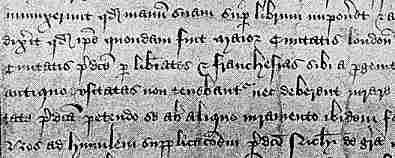

| Writ of Henry III of 1234 (British Library, add. charter 28402). (From New Palaeographical Society 1908) | |||

| The above writ of Henry III to his foresters of Essex is written in a partly cursive and slightly curly version of the 12th century chancery hand, legible but fairly hastily written. | |||

|

|||

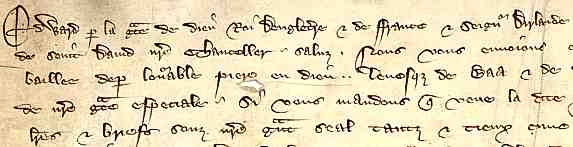

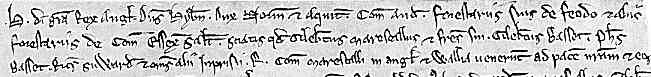

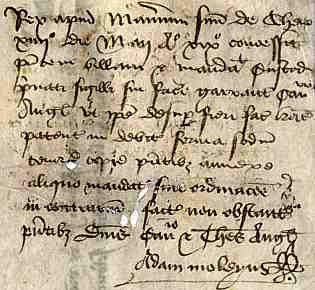

| This is the top left segment of a chancery warrant of 1349, under Edward III, ordering letters and writs under the great seal to the Bishop of Bath and Wells. (London, National Archives C.81/339/20343). By permission of the National Archives. | |||

| This chancery warrant under the privy seal of over a century later has all the characteristics of cursiva anglicana. Being an internal document between secretariats of the chancery, it does not have the more formal attributes of the script and is written in vernacular French. | |||

| In the late 14th and 15th centuries the most formal version of the chancery script changes again under the influence of the angular forms of Gothic book hand. At this point the terminology becomes seriously confused, with the terms bastard, bastarda and bastard Secretary being debated in the literature, the only point of agreement seeming to be that they are not all the same and they are not the same as the French bâtarde. I guess the main point is that literate people and government agencies around Europe were now writing to each other constantly, and styles were hybridising between book hands and document hands as well as across national or regional identities. Amongst classification purists, this leads to illegitimacy. Nevertheless, the English chancery and the law courts developed their own distinctive version. Formal documents were still being produced in Latin, but English also makes its appearance. The chancery is credited not only with developing a standard bastarda style of chancery hand, but also a more regularised, if not precisely standardised, version of what was otherwise chaotic English spelling. | |||

|

|||

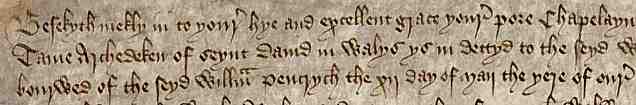

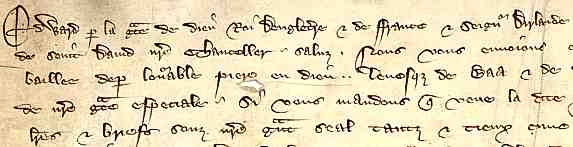

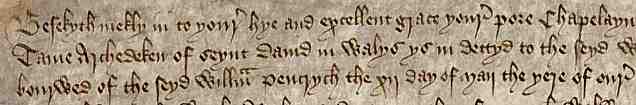

| Sample from the upper left hand corner of a petition of 1439 in the National Archives, London (E.28/file59/No.57). By permission of the National Archives. | |||

| The sample above shows a very handsome example of 15th century bastarda style chancery cursive in English in a petition to the crown from a Welsh cleric who could not get his debts paid. The loopy ascenders have become somewhat angular again and the small letters have acquired an angular Gothic quality while the distinctive letter forms of cursiva anglicana have been retained. The script is clear, legible, large, formal and elegant. This document is one that was sent in to the chancery, not one sent out by them, but petitions which were to be presented in court were copied out and corrected by chancery clerks. Petitions to chancery held in the National Archives in London are mostly written in chancery hand, although some are found written in the wild and woolly personal cursives and spelling of the outside world. | |||

| The chancery hand also appears in documents such as private charters involving ownership of property which had not been through the chancery courts. It seems that the chancery hand, or court hand as it is often called in paleography texts, was being taught to other scribes whose work took them into the legal area. Writer of the court hand became a job description in later medieval and early modern London. | |||

| Within the chancery, the differentiation between the official hand used for legal documents and the less formal hands used for internal communications and recordkeeping becomes apparent. | |||

|

|||

|

Samples from the recto and verso of petition in French to Henry VI from the abbot and convent of Notre Dame de Combe in Warwickshire. It dates from 1441. (London, National Archives E28/G8/18). By permission of the National Archives. | ||

| In this typical example, the formal petition is written in French in chancery bastarda, while the endorsement on the verso, which explains what action was taken, is written in Latin in a more informal personal cursive by the clerk of the council. He is a churchman literate in Latin, but the writing style is tailored to its purpose. | |||

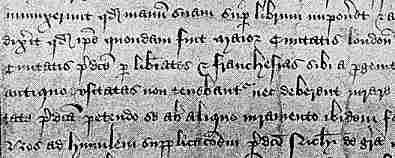

| Nevertheless, around the early 15th century the writing on the various types of rolls produced by the chancery became more formal, similar to the script used for charters, petitions and other formal documents. | |||

|

A completely random little grab from the Patent Roll of 1439 (National Archives, London, Patent Roll 443). (From Johnson and Jenkinson 1915) | ||

| During the course of the 16th century, handwriting became a generally more self-conscious process, with writing masters' books being produced with named scripts which could be reproduced for specific purposes. Various departments within the bureaucracy adopted different variants of the chancery hand for their own specific purposes, as did the exchequer. Interactions with handwriting styles used on the continent of Europe brought in new handwriting styles, known as Secretary and Italic, which developed into specialised hands for different purposes. But that is a continuation of the story here. Meanwhile, the old chancery bastarda managed to survive in certain circumstances. | |||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||