If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| The Practice of Writing in the Middle Ages (2) | |

| The development of literate process in government, law and administration was not separate from the literacy skills of the church. In England, right throughout the middle ages, the Chancellor was drawn from a senior member of the clergy, while the chancery clerks, even in the late medieval period, were likely to be at least members of minor orders in the church. As for earlier times, the question has been repeatedly posed as to whether certain figures renowned for their interest in literacy or for the development of literate mechanisms, such as Charlemagne, King Alfred or Edward the Confessor, actually had a chancery. In some ways this comes down to a question of definition. | |

|

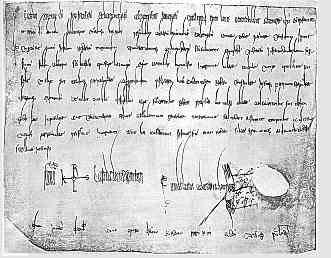

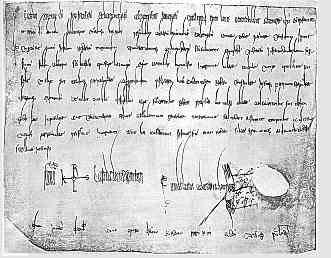

Diploma of Charlemagne of AD 781 (Marburg, K. Preussisches Staatsarchiv). (From Steffens 1929) |

| In the case of Charlemagne, there was a tradition of diploma production which had passed through the Merovingian era from late antiquity. The documents had an established formula in terms of wording, layout and script, which was notably different to the diverse scripts then in use for book production in the monasteries, although derived, like them, from New Roman cursive. While there were people closely connected to the court of Charlemagne who had learned the specialised writing, and drafting, skills to produce these very particular documents in their recognisable house style, there may not have been very many of them and they may not have been located or organised separately from one of the major monasteries. If an elite group of literate scribes working within a tightly prescribed formula to produce specialised royal documents constitutes a chancery, presumably he had one. If that group has to be a body solely attached to the court and independent of any religious institution in order to be defined as a chancery, perhaps he didn't have one. Either way, this represents the early stages of a new kind of writing literacy which would become progressively more important during the middle ages; the production of formulaic documents which had to have the right words, the right script and the right authentication in order to be acceptable as legal instruments. | |

|

|

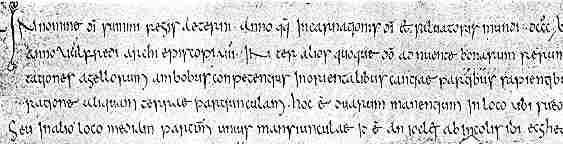

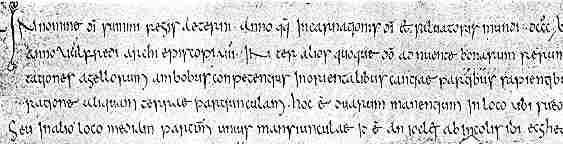

| Segment from the top left of a Mercian charter of 812 AD, recording an exchange of lands between Cynewulf of Mercia and Wulfred, Archbishop of Canterbury, from the Chapter deeds of Canterbury. (From Thompson 1912) | |

| In England before the Norman Conquest there was no tightly prescribed house style for significant documents such as royal diplomas. The scripts fitted within the range of styles of insular minuscule that were used for book production in the monasteries. The form of words was drawn, perhaps, from the formulae employed on the types of papal communications familiar to the monastic communities, with the addition of certain peculiar local elements such as the use of the vernacular, Old English, for certain sections, notably detailed descriptions of lands. Those who had been educated in written literacy within the monastic environment were drawing on their background knowledge in the service of law and government. | |

| Edward the Confessor is credited with the invention of a highly specifically English form of royal charter or writ. It was concise, with very specific forms of wording, its own unique form of double sided seal, and was written in the vernacular. This suggests again a body of scribes with highly specific training and skills, but it does not necessarily imply that there needed to be a large number of them, or that they were located in the court rather than in some nearby monastery. It is perhaps possible for one individual to have devised this new concise formula, and to have taught it to a small number of clerically trained individuals who needed to know. |  |

| Seal of Edward the Confessor, from a forged version. | |

| After the Norman Conquest, the form of words was retained, but translated into Latin. The scripts employed for royal documents changed from the home grown insular minuscule to scripts derived from the diploma hands of France, but these underwent a series of stylistic transformations over the centuries. The English Chancery developed into a formal body with its own structure and an increasing array of recordkeeping functions. It acquired a permanent home, rather than following the king around on his travels around his domain. From the 14th century, the Chancery developed its own independent bureaucracy and by 1400 consisted of around 120 clerks. By the 15th century, it had its own recognisable form of chancery hand and a relatively standardised form of English spelling. The expansion of written material produced by bureaucracies all over western Europe corresponds to a general increase in writing literacy, and to changes in educational practices. Writing literacy in some shape or form was required by many people who were not intending to become learned clerics, and was no longer restricted to studying Latin grammar in monastic schools. | |

| Even within the relatively early bureaucracy, there would seem to be some variation in the quality of writing skills required. The capacity to draft a significant document embodying the force of law and then present it in an appropriate format would seem to be a different process to the production of great piles of identical writs with the names left blank to be filled in later, as reportedly occurred during the time of Henry II, or to copying letters on to the rolls for archiving. | |

| Malcolm Parkes' term "pragmatic literacy" (Parkes 1991) applies to writing as well as to reading. People learned to write the things they had to write. From around the 12th century, the monastic schools no longer held a monopoly on the teaching of writing, and it was no longer restricted to those entering the various branches of the church. The late medieval grammar schools taught Latin literacy to certain privileged members of the laity. However, it is not entirely clear just how the practitioners of pragmatic written literacy developed the skills for their chosen careers. |  |

| The Guild Chapel and grammar school of Straford-on-Avon, perhaps more famous for its education of Shakespeare than for its medieval origins. | |

|

|

|

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|