If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| The Practice of Writing in the Middle Ages | ||||

| Just as there were different modes of reading that changed and became more widespread during the course of the medieval era, so there were different modes of writing. Just as the term reading could imply reading with the ears as well as with the eyes, so writing could be used for oral composition recorded by a scribe, as well as for the mechanical copying of transcriptions. The engagement of authors and scribes with their written texts could be complex. | ||||

|

During the early centuries of Christianity, the world of Latin literacy changed from one where a significant percentage of the population was literate and all governmental and business affairs were carried out in writing, to one where written literacy shrank to occupy the enclaves of Christianity which spread like little islands in non-literate barbarian cultures and select writing offices of the new barbarian royalty. These latter were most likely in no way separate from the monasteries, but a specialised extension of their literate functions. | |||

| The ruins of the forum in Rome. | ||||

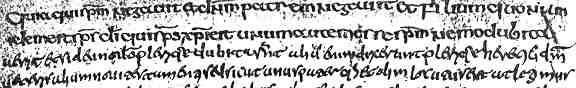

| A number of factors suggests that certain scribes who were engaged in copyist work in the first seven centuries or so of the Christian era were trained in a very mechanistic form of writing. The use of continuous script, without word breaks, suggests a very mechanical, letter by letter, approach to copying. Petrucci (Petrucci 1995) goes so far as to suggest that such works were copies for the sake of copying, rather than works for proper reading, and that some of the scribes selected for this work were actually the less intellectually able, who were trained in it as a mechanical skill. | ||||

|

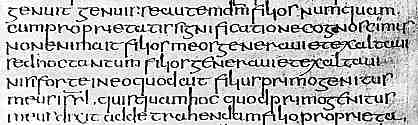

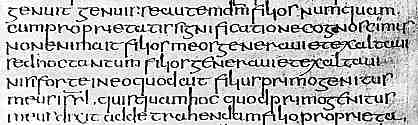

This is a sample from the writings of St Hilarius of Poitiers, dating from 509-10 AD (Rome, Archivio di S. Pietro, D.182. (From Steffens 1929) | |||

| He also claims that colophons by early scribes tend to refer only to the difficulty and tedium of the work involved, and contain prayers that this may help their eternal souls, rather than expressing pride in the product. Irregular letter forms which do not conform to any formal script type or house style, incorrect word spacing, bad Latin and a lack of appreciation of the graphic skills required to produce aesthetically pleasing letter forms are also indicative of the scribe with a purely mechanical, rather than literate, education. | ||||

|

||||

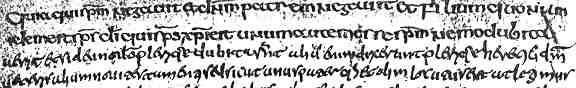

| Segment from a 7th century text of St Ambrosius on the Holy Spirit from the abbey of Bobbio (Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, D.268, parte inferiore, f. 6v). (From Steffens 1929) | ||||

| The famous early library of the monastery of Bobbio, the surviving contents of which are now dispersed among various major libraries, contains works in a range of different scripts, including examples like the one above where it changes abruptly in the middle of a single page with a change of scribe. | ||||

|

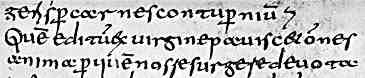

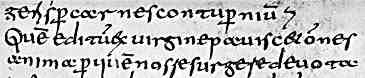

Script of Winithar of St Gall, of AD 761, from a book of hymns. (From Steffens 1929) | |||

| Even the script of a known scribe, as in the example above and identified in more than one colophon, can display these crude and ugly qualities that hint at a lack of real literacy and full appreciation of written text. Such copies, however, represent only one end of the spectrum, as elegant penmanship, elaborate script styles of consistent type and quality, and evidence of fine Latin scholarship also appear in works which indicate that truly literate writing was present among the more advanced scholars of the monasteries. | ||||

| Petrucci (Petrucci 1995) has suggested that the learning of writing in this early era was a two stage process, the first part of which involved the simple copying, letter by letter, from late Roman models. The process of learning a house style, with an elegant flow of the pen and incorporating the use of ligatures, was an extension for those destined to master a higher level of literacy. This distinction can appear even with quite elegantly produced scripts, as some works appear to have been produced by a process of copying from an existing model in a somewhat mechanical way, while others use local script families or house styles as a graphic system. | ||||

| The monastic communities and clerical ranks produced their original thinkers and authors, as well as copyists, from the early days of the patristic authors such as St Augustine through the early European fathers like Gregory the Great or Isidore of Seville, through to the resurgence of Christian philosphy in the movement known as Scholasticism which emerged around the 12th century. Among intellectual authors, the practice of writing could imply that the author sat down with a pen and did the job himself, or that he dictated to a scribe. Many older works were transcribed through many generations of copies, so that no autograph work survives. However, Thomas Aquinas, in the 13th century, was known to have written in his own hand or dictated to a scribe as the mood or situation presented itself. The term writing was used by medieval authors, whether they were actually carrying out the process of putting the words to parchment themselves, or whether they were dictating. One imagines that scribes of this type must have been rather like 20th century typists who could not only render the words of the master in the appropriate medium of the day, but may have exerted a little influence over such matters as spelling, style and grammar; educated, undervalued and ultimately anonymous. |  |

|||

| Gregory the Great with his dove for divine inspiration, as depicted on a portal of Chartres Cathedral. He may also have had a scribe. | ||||

| In this particular process of writing, the text was not necessarily committed imediately to the expensive and permanent medium of parchment. Scribes took their notes on wax tablets, which were ultimately erased. The final text was polished, corrected and rendered in a form that was appropriate for it to be copied on for posterity. This was not simple copyist's work, but a specialised process of manuscript production requiring a high level of literacy and editorial skills. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||