If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| The Roll (2) | ||

| Rolls also appeared in liturgical, theatrical, poetic, genealogical, medical and alchemical contexts. They were used for guild records. The heralds used them for keeping armorial records. The example at right records family trees, helms and crests, animal supporters as well as various heraldic devices. |

|

|

| Segment of the Rolls of the Earls of Warwick, also known as the Rous Roll, depicting Warwick the Kingmaker with all his heraldic paraphernalia, in the College of Heralds. Unfortunately, another scungy schoolbook reproduction. | ||

| The Free Library of Philadelphia has a much more elegant display of their Edward IV Roll on their web site. | ||

| A particular and specialised type of roll was the monastic mortuary roll. At the death of an abbot or other significant figure within a monastery, a roll would be sent out to all other monasteries in the order within the region. It would contain an obituary poem and prayers for the departed, and at each monastic house that it visited, prayers for the dead would be added. | ||

|

||

| Three of the entries, in three different hands, on a 13th century mortuary roll commemorating the death of Lucy, foundress and first prioress of the priory at Hedingham, Essex, from the British Library (Egerton MS 2849). (From New Palaeographical Society 1903) | ||

| The roll in the example above is over 19 feet long by 8 inches wide, so some monastic messenger had to trundle around the country rolling it and unrolling it for all the entries to be added. | ||

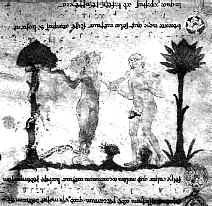

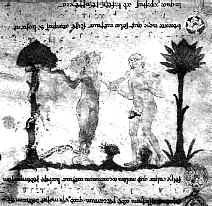

| Another specialised roll was the exultet roll of southern Italy, of which only a limited number of examples survive. The text was read by the deacon in church at Easter. Illustrations of the text were set upside down and slightly offset from the relevant passage, so that the image could be seen by the congregation as the roll hung over the back of the lectern. (See Wurfbain 1976) |  |

|

| Image of Adam and Eve and the serpent on a 12th century exultet roll (British Library, add ms 30387), by permission of the British Library. The total roll is 22 feet long. | ||

| The use of the roll rather than the codex for royal recordkeeping purposes seems to be a particularly English characteristic, and no explanations for it are particularly convincing. It is not easier to consult or store than a codex. Ask anyone who has worked in the National Archives in London. It is, however, easier to guarantee its integrity as sheets cannot be abstracted or interpolated. This argument is slightly negated in the case of the English royal records by the fact that not all letters or relevant documents were copied on to the rolls. Sometimes this was only done if the beneficiary paid for the privilege. Also, the roll entries were often made from drafts of the correspondence, so that the final form as sent out was different. The rolls also contain crossings out and corrections, and individual entries can be very difficult to locate unless the exact date of the document is known, as there were no other finding aids. Well, it was a great idea. It just didn't work very well. Other uses of the roll are for documents with a high ceremonial content, and as any anthropologist knows, ease of use is not a major requirement of ceremony. | ||

|

|

||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||