If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| The Roll | ||||

|

The roll was the original form of written material in Roman antiquity until it was replaced by the codex as the more usual form. In Roman times the roll was held sideways and the writing was arranged in a series of columns from left to right. The material of the antique roll was usually papyrus. The figure at left holds a roll as if he is reading it Roman style. The transition from the papyrus roll to the parchment codex is seen by some scholars as a process relating to the development of Christian literature. As parchment is more robust than papyrus, the body of Classical Latin literature which has survived has depended upon the selection of works by Christian scribes in the early days. This is a fascinating thought, but nobody seems to want to conjecture as to why it was so. | |||

| Figure of St John holding a scroll in the Roman manner, from the Lindisfarne Gospels (British Library, Cotton Nero D IV, f.209b).(From E.G. Millar 1923 The Lindisfarne Gospels London: British Museum) | ||||

|

Although the codex was the more usual form for written material in the middle ages, rolls were used for a number of purposes. In this era they were generally made of parchment, constructed by sewing many sheets together. The writing ran across the narrow side in a continuous single column, with the rolled ends at top and bottom. This can make them loads of fun to deal with in archives. | |||

| An archivist and a medieval historian wrestle with an ancient roll in a romantic setting beneath the historic walls of St Mary's Abbey, York. The thing was just too big and awkward to be dealt with inside. | ||||

| Rolls were used for archival purposes. Within the English royal chancery, charters, letters patent, letters close and other material sent out in sheet form were transcribed on to rolls beforehand. This is a major source for such dispersed material. The exchequer transcribed rolls of financial matters. These rolls were somewhat different in form, those of the chancery being single long sheets of many membranes sewn together and written on both sides, while those of the exchequer were multilayered sets of shorter sheets sewn together at the head. The various branches of the courts of law transcribed their proceedings on to rolls. Local officials also used rolls for recording. The use of rolls by the royal chancery was largely an English phenomenon, other royal chanceries in Europe keeping their records in codices, referred to as registers. (See Bagley 1972, also Elton 1969, also van Caenegem 1978 ) |

|

|||

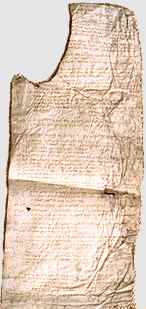

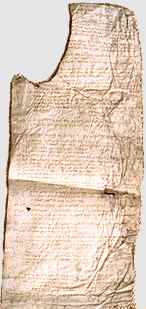

| Fragment of a Court Roll from Barnsley, Yorkshire of the mid 14th century, from a private collection. | ||||

| The use of rolls for a range of administrative and legal purposes appears all over western Europe. Court records, local records and financial records in the form of account rolls are to be found. While monastic cartularies were usually in the form of codices, there are a few examples of rolls of this type. Even a single document, such as a charter, could assume the form of a roll if it was sufficiently long and complex. In the later medieval and early modern period, inventories of a deceased person's possessions produced for probate purposes could be in the form of a roll, if they had large numbers of possessions. (I know this is true as I am currently being lined up to photograph a few of these monsters for my resident medievalist.) | ||||

|

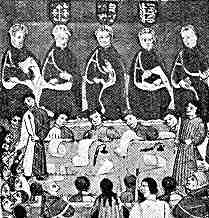

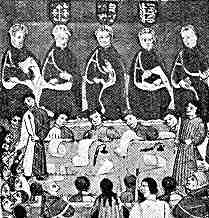

It might be not unreasonable to conjecture on how they actually kept these things under control while they were writing on them. This 15th century depiction of the Court of the King's Bench shows clerks, sitting below the judges, furiously recording proceedings on long, curling rolls which are unravelling randomly all over the writing desk. Surely for such monstrous beasts as the chancery rolls they must have had some more orderly system for entering the finely written rows of writing on the long sheets, perhaps some form of special writing desk. | |||

| Detail from a late 15th century manuscript illustration in the Inner Temple Library. Yes, it is a rather scruffy reproduction. I got it out of an old schoolbook. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||