|

| Seals |

|

The

seals, mainly of

wax, used to authenticate documents are a fascinating art form in their

own right. They are also very fragile, and with a tendency to become detached

from their documents over time. The seals on documents were often protected

in a cloth bag, but sometimes when these are opened there is a crumbling

mass inside. Many surviving seals are also badly worn and damaged. However,

a body of material exists in both public and private collections. |

|

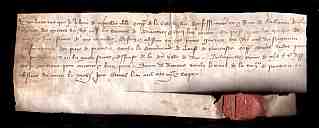

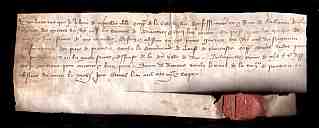

A

15th century charter with seal, from a formerly private collection. |

|

Fortunately,

seals have long been of interest to antiquarians. As well as actual surviving

seals, there are drawings and casts of seals now vanished. There are also

surviving matrices used to make seals. They have been of interest to scholars

of heraldry. However, it seems that there is still much to be learned

from the study of seals. There does seem to be a little confusion among some collectors between seals and seal dies or matrices. Seals were mainly of wax, not very durable and not likely to be found in a muddy ploughed field. The dies or matrices used as a mould to produce the seal were usually of metal, sometimes mounted on a handle or even a ring. If the writing, or legend, on such a metal object is back to front, then it is a matrix, not a seal itself. |

|

|

| Seals appear in a range of forms, and with different modes of attachment to the document. There are several intersecting traditions with this. Seals may be double sided or single sided. They may be attached directly to the face of the document, attached to a tail cut horizontally from the body of the bottom of the document, or sealed onto tags made from strips of parchment or strings of hemp or silk which were threaded through slits in the bottom of the document. |

|

A seal attached to a horizontally cut tail, on a French military acquittance of 1378, from the private collection of Rob Schäfer. Photograph © Rob Schäfer. |

|

The privy seal attached to a document of Richard II, from 1378. The seal is attached to the face of the document. |

|

Multiple seals attached by cords to the folded lower margin of a document, from a French document of 1266. |

| The seals on a document are symbols of authority and also of authentication. Where several parties are involved in a legal arrangement, there may be multiple seals attached to the document to indicate the final agreement of all parties. |

|

A document with two seals attached by parchment tags, one of them contained within a seal bag, from a French document of 1178 - 1180. |

| The bag is labelled in the same formal script in which the document is written Sigillu(m) d(omi)ni egnonis (?) comitis Suessionis, but whether it survives in there, I guess we will never know. |

| Seals were generally made of wax, and could be produced in various colours including red, white, brown, green and black. The lead seals of the papacy and certain religious bodies were exceptional. In the later middle ages, one sometimes encounters seals, either on the face of documents or attached to a tail or tag, which have a wax core that has been covered in a small piece of paper before the seal was stamped, so that it has the appearance of an embossed paper seal. |

|

| A seal of black wax covered with paper on a French document of 1551, from a private collection. |

| In the above example the seal is attached to a tail, cut not from the very bottom of the document but out of the body of the parchment. There are faint remains of a counterseal on the back, but these have been obscured by essential repairs. |

| The range and variety of seals is enormous. While the main interest of many people in seals is for identification purposes, they have an aesthetic and symbolic interest which is perhaps underappreciated. They represent the history of authority, and the changing significance of written process over the centuries. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Seals

worked their way down the social scale during the medieval era. Perhaps

the easiest way to look at them is to divide them up by the groups that

used them.

|

Decoration Decoration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|