Seal

of the city of Coventry.

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Seals of Town Corporations | ||||||

| The various powers granted to town corporations to control certain of their own affairs meant that these bodies had their own official seals. The designs on these seals are diverse, derived from heraldry, religious imagery or pictorial representations of some characteristic of the town. | ||||||

|

The seal of the city of Nuremberg. | |||||

| From the mid 13th century, the seal of the city of Nuremberg bore a design based on the imperial eagle with a crowned human head, supposedly representing the emperor. Although heraldic in style, it does not represent the arms of the city, which nevertheless do include the imperial eagle. | ||||||

|

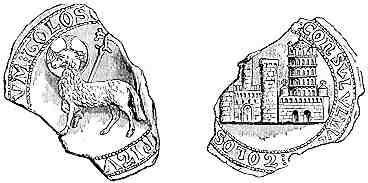

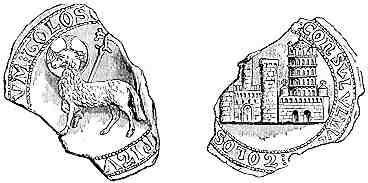

Obverse and reverse of the seal of the commune of Toulouse. | |||||

| The above example of a double sided seal has, on one side, the common religious symbol of the agnus dei, a haloed lamb carrying a flag and representing Christ. The other bears an image of the city buildings, a form of representation frequently used in town seals. Walls, castles and cathedrals were a great source of civic pride and a powerful symbol for a town. The relationships between town corporations and religious guilds are complex, but may be hinted at through imagery. | ||||||

| This is a particularly fine example of a seal depicting a town building, depicting the church of St Severus in the town of Boppard, with an eagle of the German kingdom with outstretched wings on the roof ridge. The patron saint stands in the portal of the surrounding wall. It combines imagery of national pride, civic pride and religious affiliation in one tiny disc. |  |

|||||

| Seal of the town of Boppard, on the Rhine, in Rhenish Prussia, from the 13th century. | ||||||

|

The seal of Hastings does not represent the city in a literal sense, but shows a symbolic representation of its function. The image of a warship in battle, ramming an enemy, signifies the function of the town as a port. The banners on the ship bear the arms of England and the Cinque Ports. The image on the reverse of St Michael defeating a dragon uses religious imagery with a political twist, suggesting that the devil and the enemies of England may, perchance, be one and the same. Such crude parallels would never be drawn in our sophisticated times, of course, would they? | |||||

| 13th century seal of Hastings. | ||||||

| Both sides of the town seal of Fuenterrafia, or Fonte Arrabia as it says on the legend, in Spain, from 1335. | ||||||

| The two sides of the town seal shown above combine the imagery of building, in the case a triple towered castle as the symbol of Castile, with a narrative that presumably relates to the town. One might think that the four men in a boat harpooning a whale would be more likely to relate to a Scandinavian town, but this is from the far northwest of Spain, on the Atlantic coast, so maybe such things are possible. It could refer to some local industry, or perhaps an exceptional event that took place there. | ||||||

| Pictorial seals might represent the town buildings, some incident from the history of the town, an important product of the town or a symbolic representation of some special legal privileges of the town. However, in some cases the significance of a pictorial representation is lost. Why the seal of the city of Coventry bears a bestiary image of an anatomically incorrect elephant bearing a castle on its back is anybody's guess. |

|

|||||

|

Seal

of the city of Coventry. |

||||||

|

Obverse and reverse of the seal of the city of London. | |||||

| London was the largest, most populous and most important city in England, so it is perhaps not surprising that its seal should be highly elaborate. It displays many elements including saints, heraldry and architectural views. The reverse shows one of its famous sons, Thomas Beckett, who might be associated in most people's minds with the place of his martyrdom and pilgrimage at Canterbury, but London claimed him as it was his place of birth. | ||||||

| A detailed examination of town seals might be a rewarding piece of research, as it shows us how towns represented themselves as corporate entities. It tells us not what they were like, but how they wanted to be perceived. | ||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||||