If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Aristocratic Seals (2) | |||||||

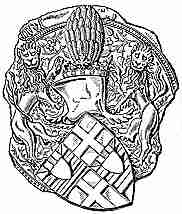

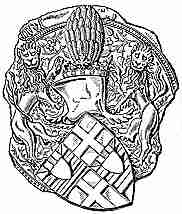

| The more complicated heraldic addenda to the basic family shield of arms also appeared on the seals of the aristocracy in the later middle ages. | |||||||

|

|

||||||

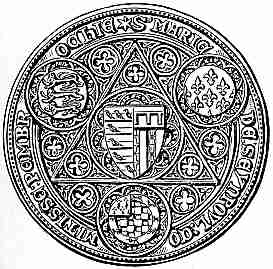

| On the left, 14th century seal of Robert de Beauchamp; centre, 15th century seal of Edmund de Mortimer, Earl of March; at right, 14th century seal of Count Gaston de Fois. | |||||||

| The examples above have not only the shield of arms displayed at an angle at the bottom of the seal, but the helm, encircled with a coronet, with crest and mantling. These late medieval attributes of the aristocracy were also displayed on funerary monuments as at right. The helm was a big clunky tilting helmet with a narrow slit to see through. The crest emerged from the top of the helm, which might be encircled by a coronet. On the seal at left the crest is the head and neck of a swan while that in the middle appears to be a plume of feathers. I am not too sure what the one on the right is supposed to be. The crest of a horse's head, emerging to the right on the funerary monument, would seem to be a rebus on the owner's name. The mantling is the twist of fabric around the helmet which is usually depicted in extravagant flowing style. The Mortimer seal also has two flanking lion supporters. |

|

||||||

| Helm with crest of a horse's head and mantling under the head of the alabaster funerary effigy of Sir Richard Redmayne, d.1475, at Harewood. The top of the helm, with the crest, is on the right. Depicted like this, it is a bit of a cross between a real object and a heraldic symbol. | |||||||

| The tomb of John de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk (d.1491) and wife Elizabeth Plantagenet in the parish church of Wingfield, Suffolk. The detail above shows his alabaster head resting on a carved reproduction of his helm and crest. | |||||||

| Just to show that these represented real objects, the tomb at left has the relics of a heraldic display above which includes the remains of two supporters and a helm and crest. The carved detail shows the head of the effigy of the duke resting on the helm with its crest of a Saracen's head. | |||||||

| So these items of heraldic display existed as real shields, helms and crests, as large representations in funerary art, and as very small representations on seals. Heraldry had become a major defining insignia of aristocratic status. | |||||||

| While women did not have the authority to dispose of property and do deals in the way that men did, women of the highest aristocratic rank were queens and heiresses and generally part of the strategic and diplomatic alliances that kept the upper class machine running. Women of a certain rank did possess seals of their own. If they had the good fortune to be widows, they even had some control over how they could use them. | |||||||

|

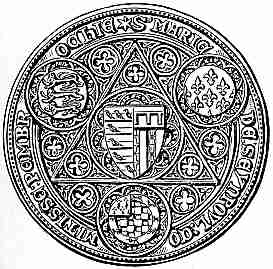

Both sides of the seal of Margaret, second queen of Edward I and daughter of Philip the Hardy, king of France. |

|

|||||

| The example from the top of the social tree above has certain characteristics common in seals of ladies in that it is of pointed oval shape, while those of male aristocrats were usually round. Before you get carried away with any sort of semiotics or natural symbolism, it must be pointed out that the pointed oval was also a common shape for the seals of male ecclesiastics. It also has a standing figure of the lady in question holding some significant attribute. This seal, significant in international diplomacy, is also heavy on heraldry. The lady bears the lions of England on her tunic while the shield of France is on her right. On the reverse, a shield of English lions is surrounded by fleurs-de-lis of France. | |||||||

|

Twelfth century seals of ladies often portrayed a standing figure holding either a hawk, not so much a symbol of blood sport as of aristocratic pasttimes, or a lily, referring to the attribute of the Virgin Mary and therefore to purity. In the example on the left, the lady has gone for both options. As with male seals of this date, the lady is identified only by the legend around the edge of the seal, not by any specific visual attributes. | ||||||

| Seal of Idonia de Herste of c.1176-1180 (British Library, Campbell charter xxv, 20). (From Warner and Ellis 1903) | |||||||

| In this 13th century lady's seal, the posture of the figure is similar, but the attributes have been replaced by heraldic shields. As with mens' seals, identification has moved from the written inscription only to the use of visual imagery. The legend is still present. |

|

||||||

| Seal of Margaret Bruce, Lady de Ros, of 1280. The lady holds the shields of Bruce and de Ros. | |||||||

| In this 14th century seal, the swaying pose of the lady imitates the style of figure sculpture of the period. It is intriguing how these tiny objects made from matrices carved in miniature by jewellers follow the styles of massive sculptures and monuments in stone. She is flanked by heraldic shields and two birds and identified by the legend around the seal. She does not appear to be holding anything, but that open handed pose could represent prayer in medieval depictions. Seals not only represented status, they also represented transactions ratified by sacred oath. | |||||||

| A French seal of Isabelle de Ghistelles, of 1330. (From de Boüard 1229) | |||||||

|

The tendency towards intricately carved seal matrices with complex heraldic designs and intricate Gothic tracery in the later middle ages, also occurred with the seals of ladies. The example at left is drawn from an original only one and a half inches (3.75 cm) in diameter. The lady in question founded Pembroke College, Cambridge. | ||||||

| Counterseal of Mary, Countess of Pembroke, of the late 14th century. | |||||||

| At the higher levels of the aristocracy, seals tended to be stereotyped, initially with standard icons indicating rank and later with the more individualised, but not personalised, attributes of heraldry. Among the lower ranks of the aristocracy and into the gentry and respectable townsfolk, seals may have been more modest, but there was perhaps more scope for imagination in their design. | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||||||