If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Bookbindings (3) | |||||

| Some bookbindings were produced that were so rare and exceptional that they must represent a different concept of what a book should be. Bindings that were works of art in their own right, constructed from metalwork set with precious stones or enamelling or carved in intricate detail from ivory, made the books look less like the usual collection of written texts and more like a sacred object. In design and construction they resembled the reliquaries made to hold the sacred bits of bodily parts or artifacts derived from the saints. They were not so much covers for texts as containers for holy things. | |||||

|

|

||||

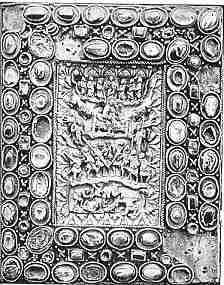

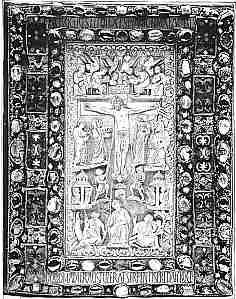

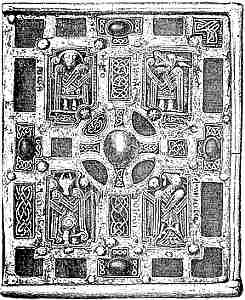

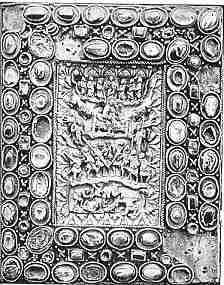

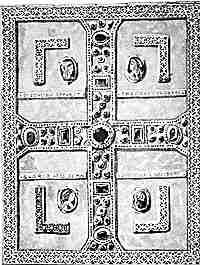

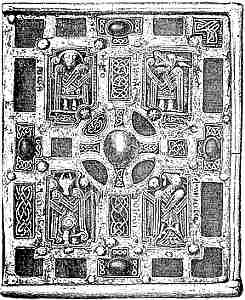

| Cover from a 9th century psalter of Charles the Bald. The metal cover is set with precious stones and an intricately carved ivory relief in the centre. In the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. | Jewelled and ivory cover of the Metz Evangelary (Bibliothèque Nationale, MS. Lat. 9383). | ||||

|

Differences in artistic style from different areas represent only variations on a similar conception of a book as a sacred object. | ||||

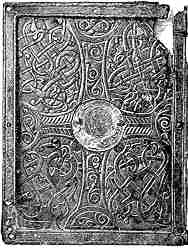

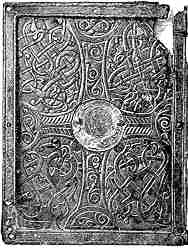

| A metal book cover from Ireland, worked with a Celtic cross and intricate interlace designs. | |||||

| Books and exhibitions of ancient Christian metalwork always seem to feature these elaborate book covers. While they are fine representatives of craft skill, it may suggest that this was the normal treatment for valuable books. In fact, these were books singled out for special treatment. The majority of surviving bookbindings from the Carolingian period, for example, are of the leather covered board variety. These are objects with a different meaning. | |||||

|

In a few early medieval examples, the relationship with a reliquary is even more pronounced, as rather than a binding, the precious outer cover is, in fact, a container. It is in effect, a shrine to a book. | ||||

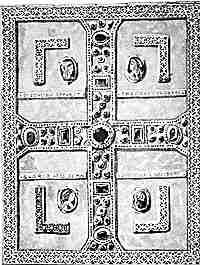

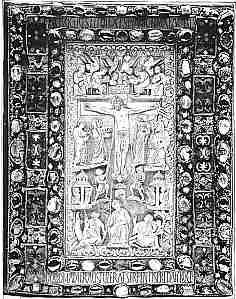

| Cover of the early 7th century book shrine of the evangelary of Theolinda, Queen of the Lombards, in the cathedral of Monza. | |||||

| The majority of these book shrines are known from Ireland, where they are known as a cumdach. There the tradition continued into the later middle ages, as surviving examples date from the 11th to the 16th centuries. However, the oldest recorded was made in the late 9th or early 10th century for the Book of Durrow. It was described by an antiquarian in the 17th century and his description survives on the flyleaf of the book it contained. I wonder where it went? According to legend, the gilt shrine for the Book of Kells was stolen in the 11th century, along with the book, but only the book was recovered. |  |

||||

| The oldest surviving cumdach, from the Gospels of Molaise, dates from the early 11th century. | |||||

| The identification of these elaborate objects as containers for sacred relics is made apparent by the history of the most famous of them, known as the Cathach, which was worn around the neck of members of the O'Donnell clan as a breastplate in war and exhibited before battles to stir up the troops. It was believed to contain the bones of St Columba and there was a curse against opening it. However, when curiosity eventually outstripped superstition and it was opened, it was found to contain an incomplete copy of the psalter. What the pious man would have made of the use put to it by the later pugnacious members of his family tree will never be known. | |||||

| In the early days when only the church was literate, it seems that holy words could have the same valuation as holy relics. It was not so much what they said, but the fact that they were there that made them sacred and spread their sanctity to the materials on which they were recorded. The medium really was the message. | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||||