|

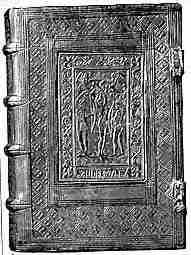

| Bookbindings

(2) |

|

This

15th century binding is reinforced with hefty, but decorative, metal plates

attached to the bindings with nails, the large heads of which support the

book when it is laid out flat. The metal clasp is also visible. The metalwork,

while decorative, is also serving a practical function. |

| A

15th century bookbinding in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. |

|

The

late medieval binding at right has leather covers cold stamped with geometrical

designs. The central sections shows a scene of the martyrdom of St Sebastian.

It's a bit hard to make out, but the saint is in the middle with his hands

tied over his head while two archers stand on either side filling him full

of arrows. There would seem to be some conceptual relationship between the

development of this form of binding design and block printing of illustrated

books. |

|

|

Late

medieval stamped leather binding. |

|

Sometimes

books were additionally equipped with soft wrappers which were attached

to the binding. The book could be wrapped up when not in use. When open,

the wrappers hung down around the book like a curtain. Such arrangements

are sometimes shown in artistic depictions and may have been used to protect

the bindings of books in regular use, like books

of hours. |

|

|

These

15th century ladies kneeling at their prayer desks have books with long wrappers

dangling over the edges of the desks (British Library, MS Roy. 2 A xviii).

No, it isn't a very good reproduction. |

|

Simple

soft covers made of parchment or leather, without the solid board lining,

were also used at times for practical non-prestigious works like cartularies,

account books or books for student use. |

|

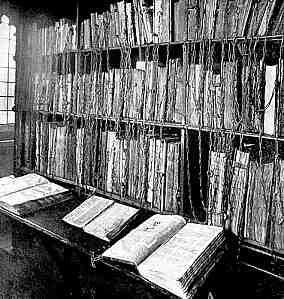

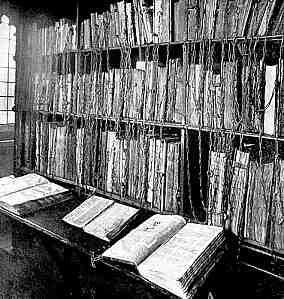

Some

books were actually fitted with chains, so that they were permanently fastened

to their shelves. While such libraries do survive, for example at Hereford

Cathedral, there is something peculiar about this as a concept. Works of liturgy

which were used in the church could hardly be dealt with in this way. It must

be assumed that the books so treated were those residing in the library for

study purposes. As the practice is recorded and survives for monastic or cathedral

libraries, it hardly seems likely that this was literally to prevent pious

men of learning from popping a large copy of the Epistles of St Cyprian under

their cassocks and absconding. |

|

The

chained library of Hereford Cathedral, although I have discovered that this much photographed library actually dates from the 17th century, although many of the books are much older.

|

| Perhaps

it was a largely symbolic reference to the value of these works as objects,

or to visually strengthen the concept of the written words contained therein

as communal property in a true Benedictine tradition, rather than the individual

property of scholars who might wish to read them in private. As a reader of

too much Terry Pratchett, I personally find the idea that it is to prevent the

books themselves from becoming animated with the power of the words inside them

and doing erratic things beguiling, but alas, unlikely. |

|

|

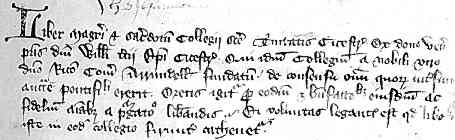

Inscription

in a book (British Library, Royal 10 A xi). |

|

The

above example indicates that the chaining of books could be a matter of some

significance. The inscription indicates that the book belongs to Holy Trinity,

Chichester and was donated by William, the third bishop of Chichester. It

concludes with the instruction that the book is to be kept firmly chained

down in the college. |

|

continued |

previous page

previous page |

Decoration Decoration |

|

|

|

|

|

|