If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| The Private Ownership of Books (3) | ||

| The increasing level of lay literacy in the later middle ages coincides with a period of greater social mobility, pursued in a highly competitive environment. The feudal system was changing in nature and becoming less rigid and newly found wealth could buy increasing status, but the display of that status was entwined with the manners, social skills and responsibilities of the aristocracy. As reading trickled down from the highest aristocratic levels of the laity, many of the works produced were part of the education of the upwardly mobile. | ||

|

||

| Above, a marginal illustration from a French language romance of the early 14th century. The full work is Le Roman de Saint Graal, in 3 volumes, and this comes from the first folio of Le Roman de Lancelot du Lac (British Library, add. ms. 10293, f.1). By permission of the British Library. | ||

| The works of romance that were commissioned by aristocratic patrons, and many of these survive in the libraries of the world, were prestige items in their own right. The stories also reinforced aristocratic values such as chivalry, bravery, good leadership and virtue. The stories contained within them were drawn from a body of material that came from sources such as the Latin Classics, tales of King Arthur, Breton legends and oral stories from all over Europe. The stories, although containing threads that could be traced to show their relationships, were not fixed, and elements were introduced that tied the stories to their patrons. They became part of the origin mythology of aristocratic families. Along with volumes of lyric poetry and moralising allegories, there was a body of literature to make lay readers into better people. | ||

| One important area of upper class knowledge was in works on heraldry. The rules of this art became steadily more elaborate from the 12th century onwards, and if your family had gained its position in life, not from fighting for a king in earlier generations, but from selling wool to Flanders and importing the wine of Gascony, then there was some study to be done. | ||

| Shields of Essex knights from a book of c.1470 (College of Arms MS. M. 10, f.78b). | ||

| There were various books of instruction on aristocratic manners and pursuits; hunting, hawking and care of the creatures involved, gardening and estate management, manners and etiquette, recreational games such as chess and cooking. It is intriguing that most of the manuscript copies of books about cooking and meal presentation that survive refer to the practices in royal or highly aristocratic kitchens. They were not so much about learning how to stuff a swan as about learning what to expect in the social environment of the upper classes. | ||

| A well ordered garden from a late 15th century work, Le Livre de Rusticon des prouffiz ruraulx (British Library, MS add. 19,720, f.214) | ||

|

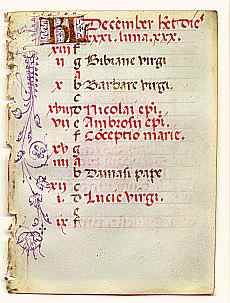

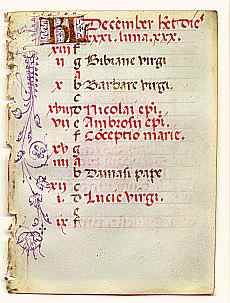

As seen in the excerpts from wills, lay people owned religious books. These included liturgical books such as missals, but the inclusion of them with other material paraphernalia of the mass in the wills indicates that they were for the use of a visiting priest. However, in the late middle ages the religious book that was produced in profusion for the laity was the book of hours. From highly elaborate artistic productions made for wealthy patrons, to elegant but modest manuscript volumes, to the much cheaper printed versions of the early 16th century, these books were the most likely to be owned and read by the laity. They read from them daily. They taught their children to read from them, in Latin as well as in their own vernacular. They represent the most common type of medieval book to be found surviving, either complete or in fragments. | |

| Calendar leaf from a late 15th century Italian book of hours, from a private collection. | ||

|

||

|

||

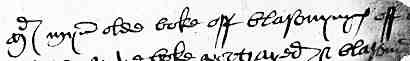

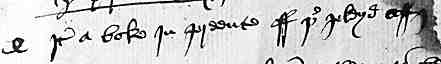

| Two segments from a late 15th century damaged list of books among the Paston letters (British Library, add. ms. 43491, f.26), by permission of the British Library. | ||

| The 15th century letters of the Paston family of East Anglia have kept historians occupied and entertained with their highly personalised accounts of life among the aspiring rural gentry. Among the letters there is a damaged scrap of paper containing a list of books that belonged to John Paston II around 1479. It is specified that these are English books, so I guess we don't know if he had any others. There are eleven items plus a memorandum of four other books. Each book evidently contains several texts, which include, among others, romances, chronicles, moral allegorical works, a printed book of chess, several books of heraldry and jousting and a book of statutes of Edward IV. | ||

| There is a script sample and paleography exercise available for this fascinating list. | ||

| The advent of printing in the late 15th century made books much cheaper and more readily available. They were still luxury items, but more affordable luxuries for the better off classes. While book ownership had been increasing over several centuries, there was a parallel increase in the conduct of legal and business affairs in writing. Bureaucratic literacy amd more widespread lay literacy went hand in glove. | ||

| There is more information about the various types of books mentioned in this section in the section entitled The Written Word : Content of Books. | ||

|

|

||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||