If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Monastic Scribes and Libraries (4) | |||||

| The accumulation of monastic libraries resulted not only in the development of written literacy skills, but in the skills of archiving and librarianship. As mentioned earlier, the first surviving library catalogues date from the 9th century. Monastic libraries were assiduous in cataloguing their books, and surviving catalogues of different dates have been used by researchers to trace the histories of individual volumes and to estimate the losses from monastic collections over the years. |

|

||||

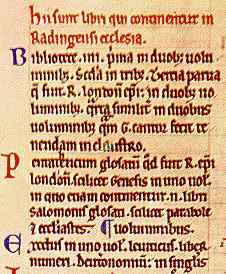

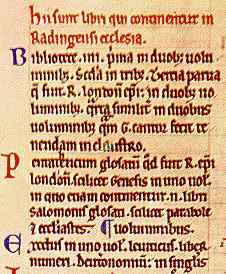

| Segment from the beginning of a 13th century catalogue of the library of Reading Abbey (British Library, Egerton 3031, f.8b). | |||||

| Catalogues of books were evidently sometimes entered on a tabula which hung in the library and could be consulted by the users. Written catalogues became not merely lists of books, but a taxanomic system in which books were classified and grouped and their location in the library indicated. The same basic techniques found in your local public library today were utilised by medieval monks. | |||||

|

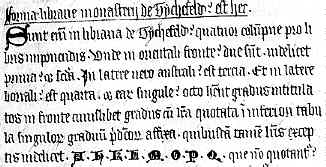

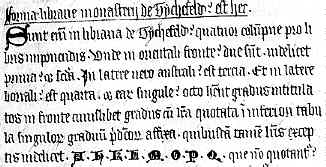

Beginning of a 15th century catalogue of Titchfield Abbey, in a private collection. (From New Paleographical Society 1903) | ||||

| The above catalogue begins with a physical description of the layout of the library. The contents of each bookcase are then described one by one and shelf by shelf. Letters have been used to designate certain categories of books; A for Bibles, B for glossed Bibles and commentaries on the Psalms, C for commentaries on the Bible, as so on. | |||||

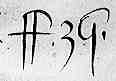

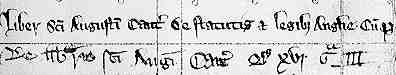

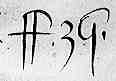

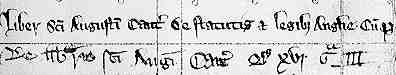

| Around the 14th century in English monasteries, the practice developed of marking the flyleaf of each book with a distinctive code which indicated the bookcase and shelf where it was supposed to reside. As each monastic institution had its own particular code, these can be used for tracing the origins of surviving books. Sometimes these consisted of a simple code, and sometimes they included inscriptions describing the work or indicating its origin. | |||||

|

Simple pressmark of the Franciscans of Hereford (British Library, Royal MS 7 A iv). (From New Palaeographical Society 1903) | ||||

|

|||||

| Pressmark with inscription of St Augustine's, Canterbury (British Library, Harleian 3644). (From New Palaeographical Society 1903) | |||||

| Over the centuries, these magnificant medieval collections have largely become dispersed. In Britain the cataclysmic nature of the dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th century left these collections open to acquisition by private enthusiasts and antiquarians. Books that were not lost or destroyed resided in the private libraries of wealthy individuals who had a passion for the past. In subsequent centuries a significant amount of this material has been consolidated again in the major collecting libraries. The foundation collections of the British Library were from these sources and collection names like Cotton, Harley, Arundel or Sloane commemorate individuals who were not prepared to just throw away the past. | |||||

|

The fragmentary ruins of the beautiful abbeys, like Rievaulx in Yorkshire, are paralleled by the fragmentary ruins of their splendid manuscript libraries. | ||||

| Even in countries which remained Catholic, various depredations and dispersals occurred. While many monasteries remained operational in France until the French Revolution of the 18th century, apparently antiquarians and scholars of the 16th and 17th centuries reduced their somewhat neglected collections in a spirit of historical preservation. In all countries of Europe, many works have found their way back into public or educational collections. | |||||

|

The medieval cloisters of the Benedictine abbey of St Pierre in Chartres were rebuilt in the 18th century. They now house a school, while the exquisite church stands a little forlorn, overshadowed by its senior sister up the hill. | ||||

| Some medieval monastic libraries have survived with some degree of integrity. The incredibly historic library of St Gall in Switzerland, one of the pioneers of literate Christianity in Europe, is evidently still there. If I don't get to see it before I die, somebody will just have to bury me there. | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||||