A

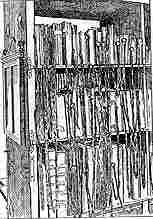

chained library.

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Monastic Scribes and Libraries (3) | |||

| Around the 12th century, changes occurred in relation to the production of books and in the provision of education. The teaching of Latin literacy shifted from monastic institutions to those run by canons, or secular clergy. The aquisition or transcription of books of the Latin Classics for monastic libraries decreased, as they were well stocked and the needs for teaching were not so great. |

|

||

| A late medieval grammar school attached to the collegiate church of Higham Ferrers, Northamptonshire. | |||

| The process of transcription of books shifted from monastic scriptoria to the shops of professional stationers. Even the monasteries tended to purchase their liturgical books rather than copy them out themselves. The production centre of the scriptorium became the curatorial centre of the library. Substantial monastic libraries contained hundreds of volumes. | |||

| Not that manuscript production ceased. The monasteries provided new authors to add to the increasing body of literate knowledge, from the learned philosophers of the florescent intellectual movement known as scholasticism, to the simpler chroniclers who kept up to date with current affairs. The writers in the monasteries were more likely to be authors and less likely to be transcribers. |

|

||

| Self portrait by the 13th century chronicler Matthew Paris. | |||

| An increasingly literate legal and bureaucratic system meant that monastic scribes were no longer being called on to draw up legal documents on behalf of the crown, but they did sometimes draw up charters to their own benefit, to be ratified with the royal seal. Sometimes they forged the seal as well, in a spirit of retrospective recordkeeping to ratify by the written word what had previously been granted by oral agreement. The scripts used by chancery scribes were notably different to those used by the monks at this time, and these self penned charters, genuine or fraudulent, can sometimes be recognised by their use of book hand. | |||

|

|||

| Segment of a charter of Henry I to the monks of Christ Church, Canterbury (British Library, Campbell Chart. xxi, 6), written in a late Caroline minuscule or early protogothic (depending on how you see it) book hand. By permission of the British Library. | |||

| In the later middle ages, written recordkeeping became as significant in the monasteries as it was in government and the law. Copies of charters were entered into cartularies, copies of letters and reports into registers. A range of officials was appointed from among the monks to attend to the business side of various aspects of running what had become substantial corporations. The monastic scribe of the 14th or 15th century was more likely to be entering lists of the prices of fish or candles or horseshoes than transcribing sacred texts. (See Tillotson 1988) | |||

|

The picturesque remains of Fountains Abbey, Yorkshire. | ||

| By the late middle ages major monastic establishments like the Cistercian Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire supported large communities and held extensive estates, requiring much bureaucratic management. | |||

| As with other property in the monasteries, books were communal property and resided in a communal library. At least, that was the ideal. The private ownership of even devotional books was frowned upon by the authorities. I have a suspicion that that is why books were often chained to their shelves in the libraries. The likelihood of outright thievery would seem to be pretty remote under the circumstances, but the books had to be consulted in the communal atmosphere of the library, not some selfish and private little corner. That's my little theory and I'm sticking to it. |

|

||

|

A

chained library. |

|||

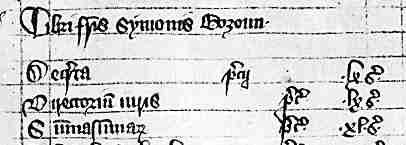

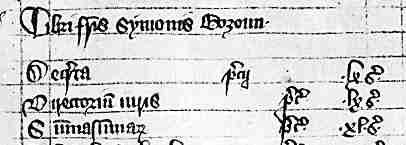

| These noble Benedictine ideals tended to become a bit wobbly at times, and in the later middle ages when the monasteries were major property owners and senior monastic personnel were the heads of large corporations and politicians to boot, they managed to collect some items of personal prestige. The example below, from a codex of diverse works, represents the first three entries from a list of 31 books belonging to Simon Bozoun, prior of Norwich. The price of each work is given. | |||

|

|||

| List of books belonging to Simon Bozoun, prior of Norwich, in an early 14th century volume of historical and topographical works (British Library, Royal MS 14 C xiii, f.13b). (From New Palaeographical Society 1908) | |||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||